The Charles Dickens Museum café is a pertinent location to meet Daisy Christodoulou, the author of the enduringly popular Seven Myths of Education, as there’s something about her that feels as if she’s sprung from a Dickens novel.

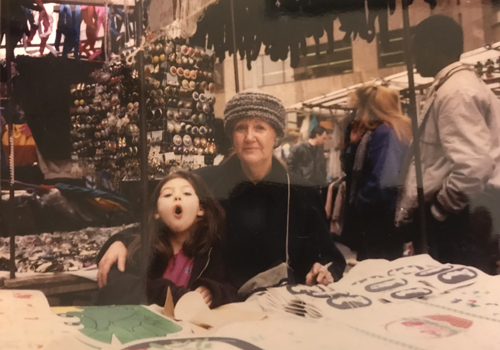

Born in Whitechapel in east London during the recessions of the 1980s, her parents worked on her grandparents’ market stall, which for half a century sold handkerchiefs, until Kleenex and Sunday trading laws wiped them out.

Thankfully her dad – whose parents were Cypriot immigrants shortly before the second world war – could work as a “sparkie”, though he had to go back to college in the 90s to get his electrician’s qualifications, having traded without them. Her mother was a hairdresser, and later a counsellor – gaining a master’s degree from the University of Greenwich.

“So when people ask were you the first person in your family to go to university,” she laughs, “I wasn’t!”

Raised on a classic inner-city housing estate, Christodoulou’s accent sounds at any moment like it might invite you to Albert Square for a few pints at the Old Vic.

But after snaffling one of the final free places at a top London private school during the penultimate year of assisted places, Christodoulou went on to become a champion of University Challenge – winning more points than her three team mates combined and romping Warwick University home to its first ever win in the show’s 45-year history.

Her myths book followed a similarly successful trajectory. Originally released as an e-book it was later picked up by Routledge, and still sits amid best-selling education text charts. It began a knowledge revolution in schools. Rarely does a Nick Gibb speech go by without the minister mentioning her work and the Conservative manifesto at the election this year pledged to develop more “knowledge-based” curriculum resources.

Did she expect the book to lead to such great things?

Christodoulou chortles, as we down tea and cakes in the garden of the museum, where she is now trustee.

“That was a surprise! I knew it would be controversial but not that it would be read by so many people.”

Her first inkling it might be taken seriously was after a day at the cricket, when she came home to find that the American academic ED Hirsch, had written a positive review.

No one is going to agree with everything. You roll with it

“When I was writing the book I was thinking ‘who will ever read this?’ It was just me pulling out a bunch of Ofsted reports. I was thinking ‘what am I doing with my time?’ But relatively soon after it came out, ED Hirsch wrote a very nice review of it and I thought ‘that is a big deal’.”

At the time she took flak from opponents to her arguments. Social media commentators particularly criticised her for being young (she was 26) and, incorrectly, for lacking teaching experience (she had taught for four years at the time).

“That’s life,” she says. “No one is going to agree with everything. You roll with it.”

Was that easy to do?

“I suppose, I would never say that it’s easy. But the things that can annoy you, and did in my teenage years – that you are a woman, that you are young, from a working-class background – you can get bitter that you’re not taken as seriously as others but that’s not helpful. It’s not good for your soul, as my mother would say.”

She laughs, and points out that she still lives near her parents, who always help keep things in perspective. One of her cousins recently spent years passing his black cab knowledge test only to find tech-company Uber spring up to ruin his career.

“That’s London for you!” she says.

It’s also a tale about the advance of technology and how it changes the workplace, something Christodoulou is looking at in her new role at No More Marking, a company helping schools harness the power of comparative judgment.

In the Dickens museum garden, she pulls out a MacBook and, within minutes, is balancing it on my lap, revealing a split screen showing two pieces of year 4 writing. Pupils were asked to write to the local council with their views about a festival taking place on a nearby common. My task is simple: I must select the better piece of writing.

“Just pick the one you think is best,” she says.

Sometimes I struggle, but I can always pick one or other piece. Though, for some reason, I keep explaining my answers out loud: “I think this one is using more interesting words, but doesn’t make sense, whereas this one has a better structure – and I think that matters more?”

The whole thing feels weird. I find myself making judgments within a few paragraphs of work, and deciding more quickly than feels right. Is that normal?

The number of biases that we have when it comes to marking is enormous.

“The thing is,” she says, “we think that when we mark work that we are looking at all the criteria. But a lot of the literature says that what we really do is make an implicit judgment and then we spend time trying to justify that.”

That chatter where I’m convincing her my choices are correct? Really, that’s me convincing myself.

Once the scores are in, Christodoulou shows how the papers are ranked, adding my scores to hundreds of others. If I had completed a few more, the programme would show how similarly I had marked compared to others teachers (thankfully we are running out of time and my blushes are spared).

The process is eerily brilliant. Which is exactly how Christodoulou felt when she first saw it. After her initial years teaching in south-west London, she became a specialist in teaching sixth-formers but eventually felt the role came too late in children’s education to make as much difference as in earlier year groups.

She moved to Pimlico Academy, and then on to Ark, where she oversaw curriculum for several years.

“I would speak to heads about the new primary tests and they would tell me reading was no problem, but they didn’t know how to assess writing.”

As a member of the commission that oversaw the scrapping of assessment levels, she was dismayed the new tests had brought them back but in an even worse format, which required teachers to moderate pupil essays.

“I was tearing my hair out trying to come up with a solution of how to do it effectively,” she recalls. “When I saw it, I couldn’t believe my eyes!”

During normal moderation, teachers spend hours looking at marked scripts and deciding if the scores are fair. Anyone identified as an over-generous marker can have their entire class’s scores marked down.

“The problem of moderation is that people will die in a ditch for one kid to get a certain grade and then another will accuse them of having low standards and it can all get quite personal,” she says.

“Moderation also relies on personal authority – who is the most senior person? It becomes about ‘if this teacher lets me have this, I will let him have that’.

“I am not being cynical. The literature on marking reinforces this view. The number of biases that we have when it comes to marking is enormous. With this system, we sat in silence for 30 minutes, judged the work, and we all agreed.

“Or, as one colleague said, ‘with normal moderation, you do it for six hours, see a handful of scripts and you leave angry with each other. This way, you don’t speak, you all agree after 30 minutes and then you can go to the pub’.”

The maths behind the system is not new. Louis Thurstone discovered the principle of comparative judgement in the 1920s, on the grounds that if you ask a person to guess how tall someone else is, they are unlikely to get it right. But if you ask which person is taller, the likelihood of a correct answer is virtually 100 per cent.

Everyone knows something is brilliant, but you might not know why

A mathematical process converts these comparisons into a rank. In the case of tall people you can use the comparisons to eventually rank everyone in height order, even though not everyone has been compared to everyone else.

Calculating the ranks was a lengthy process when done by hand but as computers advanced the promise of comparative judgement increased such that, by 2004, academics at Goldsmiths

University in London were using it to judge design and technology portfolios – a notoriously hard endeavour.

“Comparative judgement is basically a machine for making tacit knowledge explicit,” explains Christodoulou. “Everyone knows something is brilliant, but you might not know why. Now, we have a way of quantifying that.”

But isn’t the quality of writing or a piece of design a subjective thing?

“Yes, but it’s a subjective thing that hundreds of people agree on.”

The inter-rater reliability of the No More Marking method is an impressive 0.9. Even a 0.8 is considered high in psychometrics.

Another benefit of the system is that it highlights “edge cases”.

At one point during my marking, a piece completely throws me. “This kid should be a journalist,” I suggest. The writing is entertaining and snazzy, it hooks me with an exciting introduction and is written in fun, easy-to-read English, all my favourite things. But it’s supposed to be a formal letter to the local council. Is it a good piece of writing for that?

The piece is divisive, she says. Some people score it highly, loving the playful language. Others are put off by its perceived inappropriateness. By flagging such papers, moderators can then hammer out their score in the old-fashioned way and examiners can make their mark schemes clearer.

The potential of comparative judgement is huge and it’s clear why Christodoulou wants to develop it. But there’s one puzzle that still isn’t clear. Did she only apply to Warwick, or was there an Oxbridge application too? She confesses she applied to Oxford’s Merton College but didn’t get a place offer.

What happened, a disastrous interview?

“I didn’t think so,” she says, “but maybe they thought it was!”

When she beat Oxford’s colleges on University Challenge was she secretly pleased she’d proven them all wrong? A very genuine laugh rings around the museum.

“Not at all. I had a good time at Warwick.“

Really? Not even a little tinge of happy revenge?

She laughs again.

“Okay, maybe my parents thought that on occasion. My mum definitely said it once or twice.“ Thereby neatly proving that every Dickensian hero also has a great supportive cast.

It’s a personal thing

What’s your favourite book, and why?

Great Expectations by Charles Dickens. It has everything: a great plot, lots of humour, and it’s deeply moving. It’s also a book I’ve got different things from at different times of my life.

What is a memorable phone call you received?

Probably the one telling me where I would teach on Teach First. Before I got the call I had no idea where in London I’d be teaching and I can remember googling the school whilst on the phone to find out where I would be working.

What is your morning routine?

I always have porridge for breakfast, and I try to do some exercise in the morning as well.

If you were invisible for a day what would you do?

Eavesdrop on the England cricket management team and find out what they are planning to do about Ben Stokes.

Growing up, other than education, what job did you think you would do?

I wanted to be a professional footballer.

Your thoughts