Ofsted is not something Jarlath O’Brien talks about to his staff, he tells me, as we sip tea in his office, foliage framing our conversation.

He goes a little further: “I don’t give a shit about Ofsted, really. They’re nice people and they’ve got a job to do, but they can come to our school tomorrow and they’ll see a school that’s at least good. I don’t care whether they say it’s good or outstanding.”

His governors hate him saying this, but he doesn’t think there’s a big difference between his school performing at “good” and “outstanding”. “I’m not interested in chasing that badge and putting it on a banner. It does my nut in.”

I don’t give a shit about Ofsted

It’s nothing personal; O’Brien is complimentary about Ofsted’s inspectors. In his recent book, Don’t Send Him in Tomorrow, he discusses competing theories for why special schools have much better inspection outcomes (92 per cent good or outstanding) than mainstream primary or secondaries.

Some have questioned whether inspectors know what they’re looking for. O’Brien is adamant: “I’ve had quite a few inspections and pretty much every one was really on the mark. They’d worked in schools like mine for a long period of time – you couldn’t bullshit them. They knew what good progress in this school looked like.”

But “good progress” doesn’t automatically mean that students are prepared for adult life, he says. And exam results are certainly not his measure of success. He empathises with his mainstream colleagues on this one: “They have this period in August where they’re trying to work out whether they keep their job or not. And if those numbers are the wrong side of the line, they don’t.”

So if it’s not Ofsted ratings or results that hold O’Brien to account, what does? His answer becomes something of a refrain throughout my visit: “What they’re going to be like when they’re adults. That’s our intense focus . . . doing everything we can to give them the best possible chance in adult life.”

The stats O’Brien quotes in his book on life outcomes for people with special educational needs are, in his own words, “dire”. But if you’re the parent of one of those kids, “those stats are your child and there’s a nausea that comes along with that the whole time”. He feels lucky to have strong parents in the school, who “tell us in no uncertain terms, ‘We want you to do whatever you can do to make my child live and work independently’.”

He introduces me to Carwarden’s head girl, who’s been working at a nursery once a week. Employers who sign up to accept students on work experience often start off thinking they’re doing the school a favour, O’Brien later tells me, but their perceptions change. The students desperately want to do a good job and are quick to prove themselves: “They’re grafters,” he adds, proudly.

The acid test of how good we are as a school is what they’re doing when they’re 25

It’s getting them through the door that’s the challenge. The employment process is intimidating, job interviews are stressful, yet neither is representative of how good you will be at the job. So a big part of the school’s role is to open doors.

“The acid test of how good we are as a school is what they’re doing when they’re 25,” he says. If a person hasn’t managed to hold down a job by then, either they will have lost confidence in themselves, or employers won’t trust someone who’s been out of work for so long.

So there’s an obvious financial benefit to your school doing what it does, I suggest, even if it costs more per student than the mainstream. “The moral argument to me is quite obvious,” O’Brien counters. “But it doesn’t really seem to hit home.” The economic argument would be a long-term one, he says as he reels off a list of potential costs to the state (I paraphrase): supported living; some kind of benefit; cost to the NHS; a full-time carer; and for some, involvement in the criminal justice system. “So for me that seems a compelling argument. But no one has yet put the numbers on it. It would be eye-wateringly big, I’m sure, but these people are invisible.”

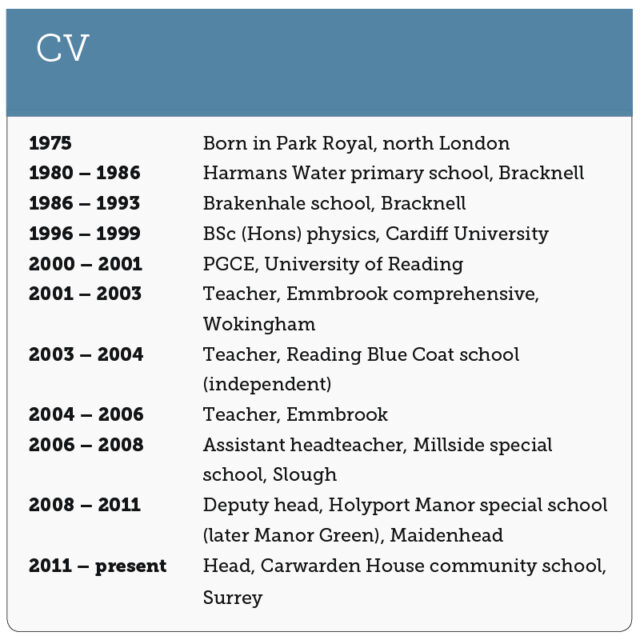

O’Brien worked in mainstream schools for five years before moving into special education – and with the self-flagellating humility of a convert, in his book describes himself as having been “blissfully unaware and completely uninterested” in the sector before what appears to have been his Damascene awakening.

Hidden away at the top of a leafy hill in Camberley, it could be argued that Carwarden House, which became an academy in 2014, isn’t helping with the visibility problem. It’s a small (140 pupils) secondary for children with “moderate learning difficulties”, most of whom have either come straight from a mainstream primary or after failing to manage in a mainstream secondary for various reasons, often behaviour. And it seems even O’Brien isn’t convinced about the system, admitting: “My vision is that schools like mine aren’t needed anymore.”

It’s a statement I keep challenging him to clarify.

So all the pupils at his school could be educated in mainstream provision, if only it were run better? “Oooh! That’s a tough question. Would I say all? No. No. Gosh, I don’t want to put a number on it. Plenty.”

He also blames the high-stakes “accountability framework” for mainstream schools, which makes them consider some kids more “risky” to keep on roll than others. “We have to remove that. We can’t have a system where a kid is deemed a risk to have in your school, just because of who they are.”

We can’t have a system where a kid is deemed a risk to have in your school, just because of who they are

So if schools for children with moderate learning difficulties were closed (not for those with “severe and profound, multiple difficulties” who, he recognises, require “highly specialised provision”) what would be his alternate vision?

It turns out that O’Brien is running two, somewhat contradictory, scenarios in his head. One involves SEND provision being built more consistently into mainstream schools.

He cites Bridge Learning Campus in Bristol, with a primary, secondary and special school on the same campus. “I’ve been on record before as saying any new school that’s built needs to have SEND provision built into it. I’d like it to be that way.”

His reasoning is that children with learning difficulties are currently seen as “other” and he wants to help to normalise them.

Co-sited schools also circumvent the logistical barriers his school encounters in trying to reintegrate some students into the mainstream: “Their lessons finish at different times, those kind of things. None of them is insurmountable but they all make it that bit harder to do.”

The other idea – which seems diametrically opposite – is to form a specialist SEND multi-academy trust, inspired by the Eden Academy in north London, which would support mainstream schools with SEND training.

When I ask why he joined the academisation bandwagon, he squirms. The answer is a pragmatic, jump-before-you’re-pushed one: “What we didn’t want to do was to get to a stage where full academisation was in the offing, and the regional schools commissioner said, ‘You’ve got two years to convert, and this is the list of multi-academy trusts you can join,’ and I would look at it and go, ‘You must be joking’.”

And given that this does indeed seem illustrative of the current political climate, it’s perhaps unfair to criticise O’Brien’s juggling opposing visions of the future – at least he’ll have a plan B up his sleeve.

___________________________________________

It’s a personal thing

What’s your favourite book?

The Selfish Gene by Professor Richard Dawkins. Watching Dawkins in the 1991 Royal Institution Christmas lectures turned me on to science. He communicates deep, complex scientific concepts with such breathtaking clarity that he convinces you that you too can understand them.

What’s you favourite non-work-related pastime?

Swimming with my children. We are uninterruptable – I have no access to email or my phone – and I’m a big believer in the therapeutic power of water.

If you were invisible for a day what would you do?

I’d go to all those places that I’m protected from in my middle-class bubble. I’d want to see what life is really like for those living in the most abject poverty, the most difficult of circumstances.

What would you want to put on a billboard?

“They need your support, not your contempt.” Having worked as a special constable and as a teacher of children with disabilities, I see many people in society who are judged to be feckless and lazy treated with contempt and disgust, and it bothers me.

A dinner party with three people. Who are you going to pick, dead or alive?

Helen Keller, who became deaf and blind before the age of two, yet graduated and campaigned all her life for the rights of disabled people. Richard Dawkins – his science writing is without peer and I share his stance on atheism. Graham Greene – he’s my favourite author (beats George Orwell in a photo finish).

Your thoughts