The education secretary says that a rise in teacher trainee applicants and improved retention rates show that her government is “turning the tide” on the recruitment crisis.

Is that the case? Schools Week investigates …

The Labour government has had little good news for its schools agenda. But new analysis this week has provided a double boost for promises to solve teacher recruitment woes.

The recruitment rise

The number of applicants accepted on to postgraduate initial teacher training (PGITT) courses for September has risen by 8 per cent to 18,309 this year, up from 16,950 at the same stage last year.

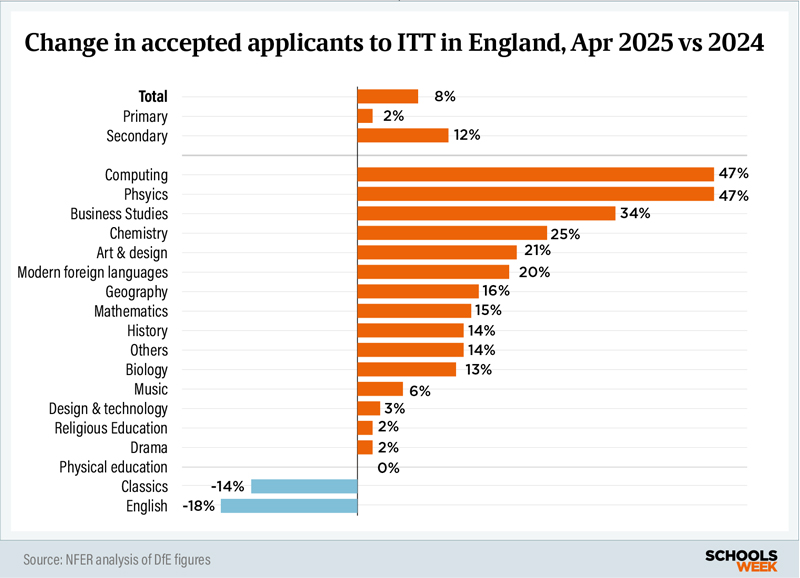

There has been a near 12 per cent rise in secondary teaching, marking an increase in all but two subjects (English and classics).

Unlike last year, the growth is also mainly from applicants based in England.

And increases have been particularly high in STEM subjects – with rises of almost 50 per cent in computing and physics.

The rise for primary trainee teachers is less, at 2.4 per cent. But Jack Worth, an education economist at the National Foundation for Educational Research (NFER), said forecasts for this September were “now looking much more positive”.

He said the rise could be down to retention payments “bedding in and acting as a recruitment boost”, a cooling labour market and the government’s 5.5 pay boost last year.

The targets cut

The government this week also revealed it was cutting its recruitment targets for next year by 19 per cent, which amounts to nearly 6,500 fewer secondary teachers.

This was because of increased recruitment, “rapidly falling” pupil numbers and “more favourable forecasts” for teacher retention.

Modelling shows 2,500 more teachers are expected to stay in the classroom over the next three years compared with previous estimates, the Department for Education said.

But targets for subjects such as physics, maths and chemistry – all of which have suffered from serious under-recruitment in recent years – have been cut.

Chemistry has been cut by 40 per cent after “more favourable retention and returner” forecasts. Physics has been cut by 37 per cent.

Paul Whiteman, the general secretary of the school leaders’ union NAHT, said the cuts were “surprising” as pupils numbers at secondary schools were set to rise for a few years.

“It’s hard to see why targets would be reduced. We need to understand more about how these targets have been calculated.”

Worth described the changes as “hefty”, but pointed out that secondary targets had “in general been unusually high in the last few years”.

Overall, it means primary recruitment is expected to beat its target next year, after missing last year’s by a record 12 per cent.

Meanwhile secondary recruitment is on track to hit about 86 per cent of its target – the highest since the 2020-21 Covid recruitment boom.

‘Green shoots’ of change

Bridget Phillipson, the education secretary, described the figures as the “green shoots” of Labour’s “plan for change”.

“Following last year’s 5.5 per cent pay award, and with hundreds of millions of pounds being invested to help us turn the tide, I’m determined to restore teaching as the attractive, prestigious profession it should be,” she said.

John Howson, the director of DataForEducation, suggested the “decade-long teacher supply problem may be finally coming to an end”.

But key contributors were underfunded pay awards squeezing pupil-teacher-ratios, falling school rolls and a “tightening labour market in graduate level jobs”.

Emma Hollis, the chief executive of the National Association of School-Based Teacher Trainers (NASBTT), said people were feeling uncertain about the economic future.

“The sector does traditionally do well when there is economic uncertainty, because teaching is seen as a safe job in a difficult job market.”

And while numbers may be improving, others are still concerned about the quality of applicants.

Paul Stone, the chief executive of the Discovery Schools Academies Trust, has seen a “pronounced” rise in applicants to his SCITT.

“Graduates are coming out of university realising they haven’t got a job and [there are] not many graduate schemes. We can’t keep up with the interviews,” he added.

The retention challenge

But he is concerned some of those graduates are “treading water” and may “sign up to get a bursary for the year to train” with no intention of “really going into teaching”.

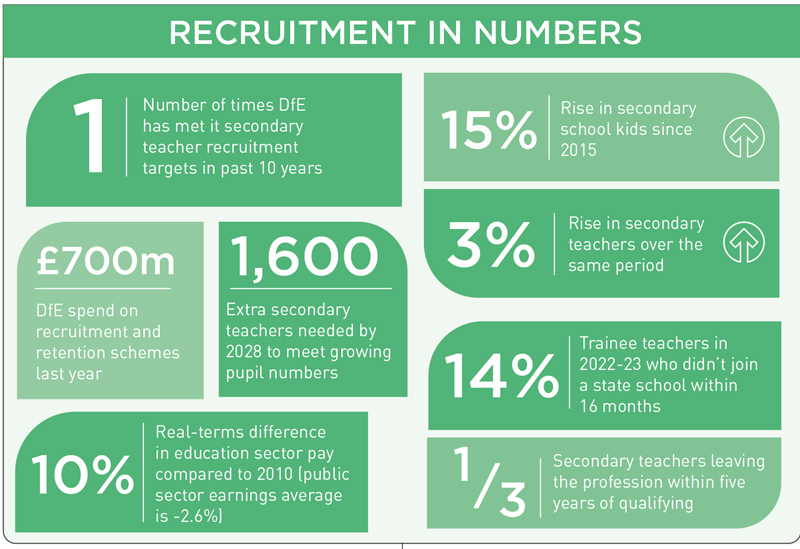

The government estimates that nearly 25 per cent of the trainees who finished courses in the 2022-23 academic year were not teaching in state schools within 16 months.

Meanwhile, a third of new teachers leave within five years.

The DfE budgeted about £700 million on financial and non-financial recruitment and retention initiatives, not including pay rises.

Of this, £390 million related to financial incentives such as training bursaries and retention payments.

Worth said while bursaries to boost recruitment in key subjects were “impactful”, few had changed since last year – yet applications in those subjects still rose.

However, the bursary was halved for English, which Worth said was the “main factor” behind the 15 per cent drop in accepted applicants in the subject.

One ‘good’ year isn’t enough

Despite the positive changes, he warned that schools are “not out the woods”.

“A single year of meeting recruitment targets would not be enough to reverse the cumulative damage from many years of under-recruitment.”

A National Audit Office (NAO) report on Wednesday found 1,500 vacancies across secondary schools and 2,500 across colleges in 2022-23. Schools also had 1,700 temporarily filled posts.

And the NAO estimated 1,600 more secondary teachers will be needed between 2023 and 2027, with secondary pupil numbers expected to keep rising.

Between 2015-16 and 2023-24, secondary pupil numbers soared 15 per cent up to 3.7 million, while teacher numbers rose by just 3 per cent to 217,500.

As a result, the average number of pupils per teacher increased from 15.1 to 16.9.

James Noble-Rogers, the executive director of the Universities’ Council for the Education of Teachers (UCET), urged the government “to be cautious” as the “proof in the pudding” would be in the final recruitment figures. The figures for 2025-26 will not be published until December.

While improved recruitment and retention should be “celebrated”, Hollis said the government “seems to be relying quite heavily on predictions of higher retention”.

“What I don’t know is…what data is telling them that retention is going to get better?”

DfE said it will consider more sector involvement in its modelling at the next annual review.

The 6,500 new teacher challenge

Labour also faces a new challenge: delivering its promise to recruit 6,500 new teachers in schools and colleges, a pledge first made in 2021 while the party was in opposition.

There have been few details after its 10 months in office – apart from it being delivered over the full course of parliament, which ends in 2029, and that numbers will be split across secondary and college sectors.

The NAO report revealed a draft delivery plan was drawn up in November, but the DfE in February “rated its confidence in achieving the pledge as a ‘significant challenge’”.

The extent to which the promise will resolve shortages also depends on how it is split across schools and further education, the spending watchdog said. The latter is facing more severe shortages as rising pupil numbers hit colleges.

The NAO has told the government to publish a full delivery plan for 6,500 new teachers after the multi-year spending review later this spring.

This should set out “objectives, responsibilities, milestones, and how increases will be measured, and subsequently, publicly report on progress”.

The DfE said it “remain[s] committed” to its election pledge of recruiting 6,500 new teachers, with recruitment to PGITT “key”.

But Daniel Kebede, the general secretary of the National Education Union, said recruitment and retention problems would not be solved without “a major and urgent pay correction, alongside significant improvements in workload”.

James Zuccollo, the director for school workforce at the Education Policy Institute, also said the NAO report highlighted “significant shortcomings” in the DfE’s current recruitment and retention strategy.

The NAO urged the government to extend its evidence base for what worked and analyse costs and benefits of initiatives to help decide where to prioritise resources.

A trust executive said he’s “concerned some of those graduates are “treading water” and may “sign up to get a bursary for the year to train” with no intention of “really going into teaching”.” I say it’s graduates gaming the system.

How ironic then that so many older, more expensive teachers are routinely subjected to informal support plans and significant additional pressures in an already pressurised job, by SLT. Could they possibly be to wanting to force them out and be replaced by cheaper new entrants?

Perhaps a comprehensive and above all honest study of why teachers leave the profession should be carried out. Until then, the new Labour government is like the old conservative government.