Spend on private alternative provision (AP) has rocketed by almost £7 million in the past three years, with councils sending more vulnerable pupils to settings that are not inspected by Ofsted or registered with the government.

A Schools Week investigation has found 26 cash-strapped councils are now spending at least £23.8 million sending pupils to private AP, with the numbers of youngsters sent to such settings nearly doubling.

We should not be using the independent sector to prop up the stretch in the system because of too many permanent exclusions

More than half of councils that gave reasons for the rise in private AP said it was down to school exclusions or “increase in demand”.

It is the first time the cost and use of private placements for excluded or dual-rolled pupils has been revealed.

Private providers are less likely to be inspected by Ofsted, and those that do have poorer ratings.

Kiran Gill, the founder of the AP teacher training programme The Difference, said it exposes how many vulnerable pupils are being “brushed under the carpet”.

“Currently, many of the country’s most vulnerable learners are in some of the settings with the least safeguards and state oversight,” she said.

At the same time, too many exclusions and insufficient places in state provision meant “local authorities’ budgets are haemorrhaging because of the cost of private AP”.

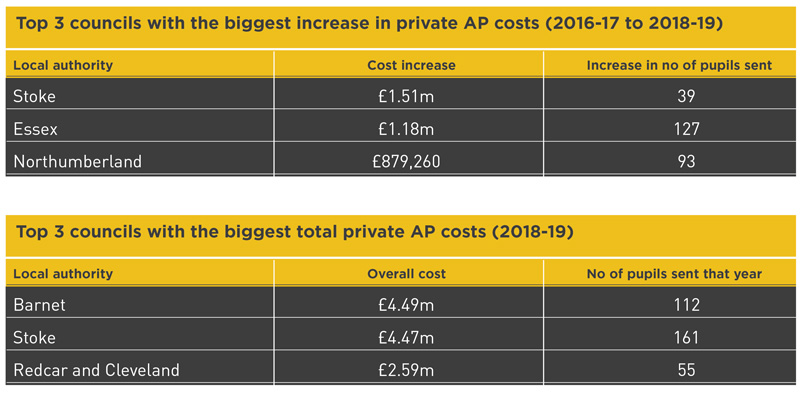

Schools Week sent FOIs to all 152 councils. Of the 60 that responded on time, 26 issued full figures for their private AP spend. Costs rose from £17 million in 2016-17 to £23.8 million in 2018-19.

The number of pupils sent to the settings rose from 1,037 in 2016-17, to 1,925 this year.

Several providers named by councils didn’t turn up anything from internet searches – such as websites or phone numbers.

West Sussex council revealed that “as many providers are not registered with Ofsted, it is not possible to identify” the pupils who attended them.

Of the 15 registered private alternative providers that “made themselves known” to West Sussex, Schools Week could not find Ofsted reports for seven.

One provider aimed to use “fishing” to improve pupil school engagement. Another council admitted it abandoned private AP after outcomes were too poor.

The findings come as the government pledges to improve AP following Edward Timpson’s review of exclusions published last week. The former children’s minister found “too much variation” in education quality in the sector.

Gill has now called for the “issues with private AP” to be included in the government’s consultation on implementing Timpson’s reforms. It will be launched in the autumn.

Of the ten councils to provide reasons, six cited school exclusions or “increased demand”. For instance, Rutland pointed to “schools being unable to meet need and the risk of exclusion” as key.

Our most vulnerable learners are in settings with the least state oversight

Gateshead council said delays in opening a state pupil referral unit had caused costs to rise by £192,000 from last year, while Stockport, where costs rose by £297,000, said private tutors were increasingly used.

But Tower Hamlets council in east London reduced private AP costs by £21,000 this year “because our own state-run AP has provided better outcomes”.

Research last year by The Difference and FFT Education Datalab revealed 116 registered private alternative providers were open in 2018, of which 109 were inspected by Ofsted.

Only 72 per cent were “good” or better, compared with 89 per cent of state AP.

Government guidance states settings that provide education for at least 18 hours a week are “generally” considered to be operating full-time. The same guidance stipulates that independent schools providing full-time education must legally be registered with the government. However there is no legal definition of “full-time”.

Some private providers used off site may also be visited as part of an overall school inspection.

In West Sussex, Angling4Education, which according to the council has taken referrals from 25 schools and “uses activities such as fishing creatively and flexibly to achieve positive outcomes”, has no Ofsted report or DfE number.

Pupils in West Sussex could also spend “two or three days a week” at Near To School, but again the provider has no Ofsted report or DfE number.

Both were contacted for comment.

One private provider in Stoke called Want2Achieve posted a youth mentor job this month, but has no evidence of being registered or inspected, while another, It’s What You Say, cannot be found online. The council was contacted for comment.

Dave Whitaker, the executive principal at Springwell Learning Community, an alternative provision school in Barnsley, said many small private providers did a “great job” but they should not be “relied upon” to handle increases in the numbers of excluded pupils.

“Why aren’t we doing strategic planning for our state sector? We should not be using the independent sector to prop up the stretch in the system because of too many permanent exclusions.”

Meanwhile Debra Rutley, executive head at the Aspire AP academy in Buckinghamshire, said private AP could be financially unstable.

Several years ago Buckinghamshire schools used a company for vocational qualifications, but they closed “one Sunday night” after going bankrupt, she said.

“We ended up having to force our way into the building to get student coursework, and put in a recovery package to get the students through the qualification.”

Last year Ofsted also warned MPs that private companies were profiting by offering illegal AP that gave pupils “a very limited educational experience”.

An Ofsted spokesperson said the inspectorate had “concerns about the quality of private alternative provision” as a “largely uninspected and unregulated sector”.

The Timpson review has called for ministers to “significantly improve and expand” AP facilities, with the “right level of capital funding” a priority for the spending review.

However the government refused to commit to the pledge – despite recent research showing one in three local authorities have no spaces in pupil referral units.

A DfE spokesperson said guidance was “clear that a local authority or school responsible for commissioning the alternative provision must assure themselves that the setting is registered, where appropriate, and provision is delivered by high-quality staff with suitable training, experience and safeguarding checks”.

Councils’ spend on private SEND settings continues to soar

Council spending on private special educational needs provision has risen by nearly £80 million in three years.

Cash-strapped town halls spent £368 million on private SEND providers this year, up from £290 million in 2016-17, Freedom of Information requests show.

Over the same period, the number of pupils sent to private special needs schools rose by about 1,600 – from 6,331 to 7,957 this year.

Councils said state provision was struggling to keep up with increasing numbers of pupils diagnosed with complex needs.

Bedford Borough Council explained that pupils are “not refused placements on the basis of a budget being overspent. If they need a placement, we have no option but to find one”.

Schools Week sent FOIs to all 152 councils. Of the 60 that responded in time, 51 provided full figures on private SEND provision spend since 2016. It means the true cost across all councils is likely to be much higher.

The councils with the biggest increases in spend were Kent (£10.6 million increase), Lancashire (£5.3 million increase) and Staffordshire (£4.6 million increase).

The biggest overall spend by councils this year was also in Kent (£33.5 million), followed by Leicestershire (£22.8 million) and West Sussex (£20.1 million).

Only five councils saw their costs drop: Barking and Dagenham, Bromley, Greenwich, York and Barnet.

It follows Schools Week’s revelation two years ago that councils were spending millions of pounds on independent places at double the cost of state-run places.

One private SEND placement cost about £52,000 per in 2015-16, compared to between £10,000 and £30,000 for a state-funded place.

Correction: Schools Week updated this story to clarify government guidance on providing “full-time” education.

But what’s the alternative?

Previous articles by Schools Week have pointed out, for example, that Warwickshire council closed all of its pupil referral units in 2012. If there aren’t any maintained PRUs or AP schools to use then whether you want to or not the only choice is private AP.

No excuse for sending pupils to, and spending public money with, entities which are not registered or inspected though.

And for pity’s sake, I thought this had been done to death before but it clearly hasn’t penetrated enough …

Stop peddling the falsehood that is “Government guidance requires all settings that provide education for at least 18 hours a week to register as schools, which means they will be inspected.”

This is NOT TRUE.

First of all, and presuming none of the children have an EHC plan of a SEN statement, you can provide as much education as you want for four children or less with no need to register.

Secondly, the figure of 18 hours is merely illustrative. The requirement to register kicks in when “full time education” is provided for five or more children. DfE have said that they would consider an institution to be providing full-time education if it is intended to provide, or does provide, all, or substantially all, of a child’s education. DfE goes on to say that they would consider providing more than 18 hours per week is full-time education, but this is not a threshold.

It is perfectly possible to be deemed to be providing full-time education if less than 18 hours per week is provided.

I understand that this is more nuanced than the simplistic “18 hours” tagline, but as specialist education publication it would be nice if Schools Week could actually get this right.

Agreed, but it’s actually worse because it’s 5 pupils or 1 with SEND. I suspect that no one wants to define ‘full time’ because then there’s a legal yardstick that has to be paid for.

Personally I think it is better that there is no clear definition for “full time” precisely because it would result in people playing the system. Without wishing to repeat previous postings, if you click on this link you can see a discussion I had with Janet Downs on this point …

https://schoolsweek.co.uk/open-sewers-and-rat-traps-in-rooms-the-appalling-conditions-at-englands-illegal-schools/

I agree, because you’re looking at quantity, not quality. It’s just one of the things LA’s regularly say they want when dealing with home educators without, it seems, thinking that once they’ve got it it’ll also apply for alternative provision and provision for kids they can’t get a school place for.

Should we look at the issue as one of cause and effect then we may reach the following conclusion. If you create an environment that some can’t tolerate, it is ‘toxic’ to them, then they will seek to exit that environment. So if more pupils are needing to enter alternative provision then should we be asking what is it about the school environment that is making this happen? If the bath water was too hot we would add cold not get out and find another bath!

Brilliant analogy. Please may I borrow it for future use?