When Rachel Filmer tried to launch a petition in December demanding that ministers commit to laws mandating support for pupils with SEND, it was turned down by the government website.

She was told that, because such plans were not under consideration, the petition was not valid. But she pushed back, and the petition was published, to little fanfare, in April.

It exploded last week after a government adviser told Schools Week that ministers were considering reforming education, health and care plans (EHCPs) as part of a wider SEND shake-up.

The backlash hit the pages of national newspapers and has filled MPs’ inboxes – offering a glimpse of the tinderbox the government could be walking into with its SEND reforms. The petition now has around 55,000 signatures.

“Parents are absolutely panicked,” Filmer told Schools Week.

“Many have fought for three, four, five years to get that plan – and now they fear it will be removed. These parents have clear, recent memories of how their child was failed – they are extremely worried.”

The reaction gets to the heart of Labour’s biggest hurdle with any SEND reforms: how to change a system everyone admits is broken without diluting support, or the commitment of support, for our most vulnerable pupils.

Schools Week investigates…

The funding issue

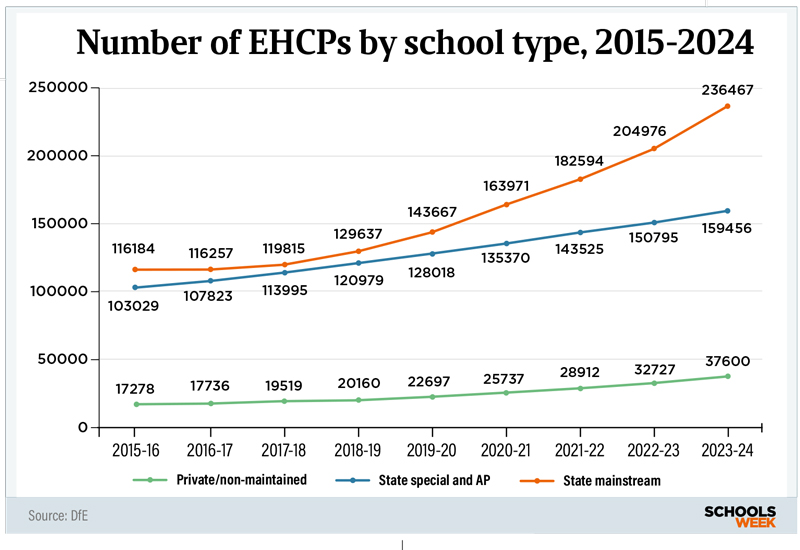

Experts drawing up reforms are discussing changes to EHCPs, Christine Lenehan, the government’s “strategic adviser” on SEND, said last week. One consideration is whether such plans should only apply to pupils in special schools.

“Do I think the structure around EHCPs will change? Yes, I think it probably will, because it’s not fit for purpose,” Lenehan added.

An EHCP is a legally binding document outlining the support a youngster with SEND must receive. But many are of poor quality and plagued by delays, leaving families waiting years for support as councils struggle with rising demand.

Writing for The Independent, Lenehan said plans have “become emblematic” of a “highly adversarial” system. “SEND support must be normal and routine – not something special or exceptional,” she wrote.

“The conversations I’m having are not about whether we do or don’t scrap EHCPs – they’re about fixing these systemic issues that make SEND support so hard to access.”

An outline of wider SEND reforms is currently being considered by Downing Street, Schools Week understands.

Providing better support would reduce EHCP numbers

Lenehan offered “every reassurance that for hundreds of thousands of children with EHCPs, there will continue to be high-quality support”.

But a key concern is whether the government can provide the funding required to make mainstream schools more inclusive, which will be the bedrock of any new system.

“If the government wants to provide better non-statutory support – you don’t need to change the existing framework – and EHCP numbers will go down really quickly,” said Filmer.

“But schools and teachers know through bitter experience the resources they need aren’t frequently available to them,” the mother of two autistic boys added. She fought for support at a tribunal in 2021 and has since been helping other families.

“If we were in a period of investment – to improve services – they [government] may get a different response. But we know there’s a financial catastrophe.”

EHCP critics have concerns

Even those who have publicly criticised the quality of EHCPs have concerns about reforms being driven by “cost cutting”. Any savings should be a “by-product of better general inclusion”, said Ben Newmark, a teacher and SEND expert.

“Removing EHCPs and the individual attached funding is a big risk in a system that isn’t yet generally inclusive enough,” he added.

“EHCPs are lifebelts we need because of sinking ships. We won’t need them when the ships aren’t sinking, but until then removing them without confidence the ships are fixed could mean more drowning.”

But the counter argument is that the system won’t become more inclusive until the funding system is changed.

Funding attached to individuals through EHCPs “forces” schools and parents to “emphasise pupil deficits” and has “contributed significantly to current issues”, Dr Peter Gray, co-coordinator of the SEN Policy Research Forum, has said.

One idea is for more targeted provision to be funded directly in schools, so that support can be accessed without the need for formal assessment or diagnosis.

Another is for some funding to be pooled and distributed locally, to drive more collaborative behaviour between schools.

The politics issue

But policymakers also face a huge political hurdle. “I have no doubt that those MPs who, like me, are new to this House will have been blown away by the scale of the SEND crisis in their constituencies,” Labour MP for Suffolk Coastal Jenny Riddell-Carpenter told Parliament in February.

“Parents are quite literally crying out for help, and we must listen to them and act.”

Munira Wilson, Liberal Democrat MP for Twickenham, said that “barely a week has gone by when we have not had questions or debates” on SEND.

Any legislative changes – such as reforms to EHCPs – would need to go through Parliament.

“This should be a shoo-in for a government with a majority like this one,” Catriona Moore, policy manager at SEND legal advice charity IPSEA, said. “But MPs’ offices are bursting with casework for constituents desperate for help.”

Nearly one in five MPs elected at the 2024 general election (115) won in a marginal seat – meaning the margin of victory was 5 per cent or less. Just over 50 of these were Labour MPs, the most of any party.

“MPs, especially those with wafer-thin majorities, need to ask themselves if reducing the number of children with special educational needs or disabilities who have a right to support in school is really the solution, and something they want to be part of,” Moore added.

‘Not going to screw families over’

But one source close to the reform process said advisers “are not doing this to screw families over. Nowhere in the terms of reference does it say they’re removing children’s rights.

“The current statutory vehicle stops decisions being made quickly and efficiently – they have got to look at how you make assessments and secure provision much quicker and nearer the child and school.”

If the SEND system issues are not resolved now, they also fear it “becomes like social care – just so broken and big, it gets shunted to each new government to solve”.

“Those involved feel this is the last moment the SEND system is fixable in this Parliament,” the source said. “Number 10 needs to grasp that.

The communications issue

Another major concern is the government’s political ability to successfully “land” any reforms, particularly around communications.

Labour MP Helen Hayes, chair of the education committee, said SEND was “the issue that MPs raise with me above all others”.

“Understandably anxious” stakeholders should be “meaningfully engaged and consulted with” before any changes are announced. “The government needs to handle its communications carefully and sensitively.”

Lenehan said last week that “any system that the government looks at will have a full consultation process … and a long lead-in time in terms of implementation”.

But campaigners already fear their voice is not being heard.

“There’s been lots of lobbying to reduce these [legal] rights as it is [from councils],” added Filmer. “The fact they are listening to that, and not families, while there is a SEND inquiry ongoing means it looks unlikely they are going to handle it better.”

‘Learn from mistakes on welfare reform’

The government is struggling with other controversial reforms. A U-turn on winter fuel payments for pensioners was confirmed this week and there are reports it is considering concessions to its disability benefit reforms.

One policy expert said Labour must learn from the welfare changes that reforms “can’t be tagged into the conversation about making savings”.

“Cutting budgets for SEND would be a disaster,” they added. “Nobody should be in a position where there is less money”.

But Emma Bradshaw, CEO of the Alternative Learning Trust, said “there is going to be pain – but we have to have pain”.

“Everyone in the system – from parents to schools and other agencies – is channelled into this funnel to get an EHCP. Can we get that resource in to meet needs without it? If we can get this right, we can get it right for a massive percentage of pupils.”

David Thomas, a former Department for Education policy adviser, said the government must “lead with how the reforms improve outcomes for children, as well as the taxpayer”.

“They will also need to win trust in the new system before it asks people to surrender the old.”

And Filmer added: “No one is desperate to cling onto the system as it is now – it’s devasted and not functioning properly. But we are desperate to hang on to those legal protections. If that goes away, what options will parents have?”

I’m sure there are plenty of issues with the EHCP system once you achieve one. I’m no expert (thankfully). My understanding is that the amount of money each LA gets is not based on the actual need that EHCP applications prove to exist. I think SEND is still allocated on historic norms, and 151 LAs have to (re)create a multi-level EHCP system to divvy up the money they are given the best way they can rather than the need that presents itself. 151 LAs reinventing the same wheel was never going to be a recipe for success. The country needs needs a national formula the EHCPs and a nationally recognised system for assessing need and then the money must simply flow from the centre. The reason that this doesn’t happen is that government knows there isn’t enough money to meet need, a bit like social care, and the population are interested in paying the taxes necessary to fix this.

The idea seemingly expressed in this article that if only you fix SEND inclusion in the mainstream, the EHCP problem fixes itself is laughable, mainly because the the inclusion system in the mainstream is already laughable.

Special schools with all their special facilities and all their specialist personnel on site get an actual £10.000 per pupil basic funding. ECHPs top up from there. Mainstream schools with little or none of those facilities, needing to ship specialists in from outside, get an assumed £10,000 which in reality is £1000s short.

First of all, the NFF has many factors beyond core funding (AWPU and lump sum) that cater broadly for low-cost, high incidence SEN (LCHI SEN). These are things like Deprivation, Low prior attainment, even EAL. Every classroom in the land is likely to see some of this need so it has to be *included* in mainstream settings. For Primary schools in rural settings like Worcs (which adopted the national settings for the NFF almost from the outset) if a child ticked every additional need box, the total funding would come to about £5,500, that’s a minimum of £4,500 per EHCP pupil that has to be “found” (taken from) non-SEN children.

With so many additional need factors in the NFF it’s hard to see the wood for the trees, too many potential issues to consider. Fortunately, there is a huge simplifier that provides real clarity on this issue. The NFF has a notion called the funding floor. This basically states that if all the various additional needs and core funding doesn’t add up to the basic minimum funding the country deems necessary to provide the barest minimum of primary education, then you get that minimum instead; it’s about £4,600, £5,400 short of where EHCPs kick in. The simplifier is stark. Not only is there no money for HCLI SEN, (the bogus notional SEN), there isn’t even any money for the additional needs that have been identified. Just the basic minimum. If you’re looking for the source of a broken system, you need look no further.

There isn’t a single penny of High cost, low-incidence SEN provision in the NFF. Notional SEN is a lie. Arguably it is the biggest lie in the whole system. Certainly it is the first thing you have to fix if you are serious about solving the SEND funding crisis. Honesty about the scale of the problem is the missing ingredient and it will cost a fortune to fund once added. No government has had the political will to address this. The public probably doesn’t have the stomach to pay for it.

Worcs Academy Trust Business Manager

Mainstream classes have so many pupils they can’t safely accommodate 1to1 teaching assistance for EHCP pupils. The constant movement of pupils between classes and the sheer numbers mean secondary education needs to be closer to primary school education model for those pupils with an EHCP to access mainstream education successfully. With the constant pressure for exam results those less able, recognise the subtle unwelcoming vibe they get and schools who undertake excellent care of EHCP pupils are heavily punished by getting inundated with higher numbers of children with EHCPs with much higher pastural care costs and who aren’t going to positively add to the academic league table position.

Special schools are full to capacity and even independent special schools are so full they are more choosy that pupils fit into their cohort of current pupils. With 105% & 110% PAN in all schools it is easy to reject EHCP children from mainstream attendance.