Top grades at private schools plunged this year when exams returned – despite results for grammar schools, which also have more higher-attaining students, hardly falling.

While some experts suggested the data may support arguments that independent schools inflated last year’s grades – which were awarded by teachers – others urged caution on drawing conclusions.

Schools Week takes a look at what the data tells us …

Private school top grades plunge …

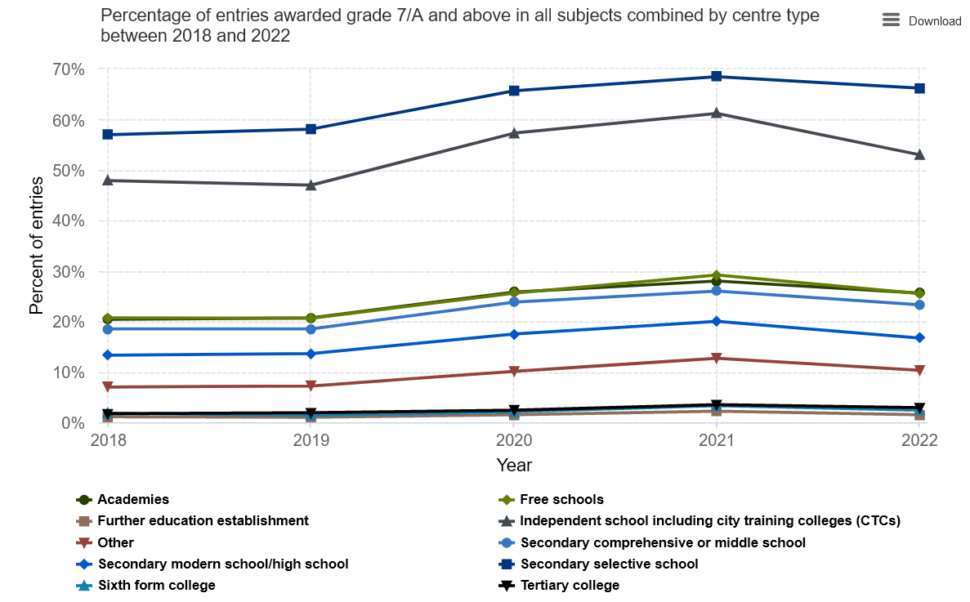

The proportion of 7 to 9 grades issued at GCSE rose from 21.8 per cent in 2019, to 30 per cent last year.

Ofqual planned to haul back grades this year to a “midway point” between those two years, before returning to pre-pandemic standards next year.

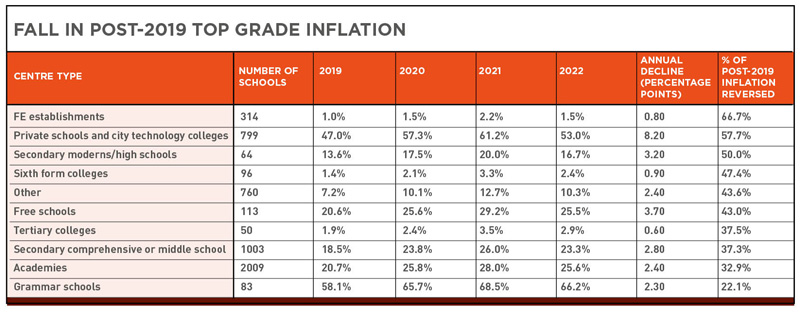

Overall, 37 per cent of the post-2019 inflation of grades at 7 and above was wiped out this year.

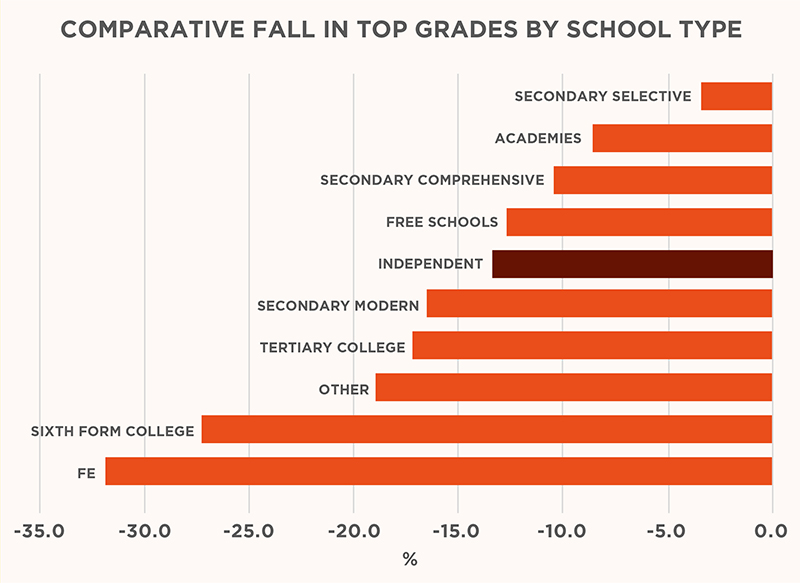

But analysis by Schools Week shows that private schools saw 57 per cent of their post-2019 grade inflation reversed.

Dave Thomson, chief statistician at Education Datalab which also analysed the data, said previous studies suggested that private schools dished out “more generous GCSE grades than might be expected. The [GCSE] results seem to support that.”

… and fall well behind grammar schools

The rise in top grades at private schools in 2020 and 2021 closely mirrored the rise in grammar schools – which select pupils based on their ability at age 11 so are also likely to have more pupils on the boundaries of top grades. (This was used to explain why private schools saw larger rises in top grades when exams were cancelled).

However, grammar schools saw just a 22.1 per cent drop in the post-2019 inflation of their 7 and above grades.

Professor John Jerrim, from the UCL Institute of Education, said the new findings were “interesting”, but called for more analysis to see “how this looks at other grade boundaries and also when subject mix is taken into account”.

For instance, around 500 independent schools in the UK sat Cambridge IGCSEs – rather than GCSEs that state schools favour. They are also much more likely to study subjects such as Latin.

And analysis looking at the grade 4 “standard” pass rate – rather than top grades – shows the difference is less stark.

The table below shows grades 7 and above (left) by school type, compared to grades 4 and above (right).

Jerrim added: “The other thing we may want to ask is how selective schools have managed to do so well this time around compared to other centre types – have they managed to make particularly good use of the forward guidance?”

‘Not enough data to accuse anyone of cheating’

Jerrim had previously warned against concluding private schools “fiddled” their teacher grades after A-level results saw a similarly large drop in top grades for the institutions.

When he looked at the relative difference of top A-level grades issued – private school pupils were around 20 per cent more likely to receive an A/A* grade at A-level in 2021 than this year.

But this was similar for academies, comprehensive schools and secondary moderns, too.

Comparative analysis for GCSEs also shows a similar picture.

Private schools saw a bigger drop in top grades than academies and secondary comprehensives, but similar to that of free schools – and less than secondary moderns and sixth form colleges.

Barnaby Lenon, chairman of the Independent Schools Council, said that “trying to make comparisons with last year’s results is not advised given the unique nature of the assessment system”.

Ralph Lucas, Editor-in-Chief of The Good Schools Guide which reviews schools, added “this is certainly not the data in this to accuse anyone of cheating. But there is enough to say teacher assessments are not acceptable for judging children – we need something independent of that.”

But Robert Halfon, chair of the education select committee, was more forthright – suggesting the issue might be set for closer political scrutiny.

Commenting after the Sunday Times reported single-sex private schools recorded among the biggest drops in grades, he said: “Clearly private schools milked the teacher assessed grades system because there was a huge amount of grade inflation last year compared to most state schools.”

What does this mean for colleges and secondary moderns?

But the data shows further education colleges and secondary modern schools – those that share areas with grammars – saw huge drops, too. So, does it suggest those school types also cheated?

Ian Widdows, founder of the National Association of Secondary Moderns, said: “If you’re using a term like ‘fiddling’, you have to make sure the data is robust. And Ofqual’s isn’t.”

The data is from the National Centre Number (NCN) Register, managed by exam board OCR.

The NCN is self-reported – so schools get to choose which category they fit into, and some fit in to multiple categories. It means the centre numbers in the data do not match the actual national numbers.

For instance, the Ofqual-published data lists just 83 grammar schools (there are actually 163) and just 64 secondary moderns (there are at least 220, depending on how you categorise them).

The categories of schools are also strange. For instance, private schools are recorded in the same category as “city technology colleges”.

Whereas further education colleges are “lumped” into an “amorphous FE establishment group comprising 314 centres,” says Julian Gravatt, deputy chief executive of the Association of Colleges.

Following recent mergers, there are just 175 further education corporations in England.

He also points out the small number of pupils in the FE analysis. Most college students studying GCSEs are those retaking English or maths – those who scored a grade 3 or below and are aiming for a grade 4.

“It’s worth looking at the detail before hurtling towards conclusions,” he added.

School variation is ‘complex’, says regulator

Widdows has complained to Ofqual about the data.

A spokesperson for the regulator said the onus is on schools to provide the right information, and that it is the “best data available”.

They added: “Ofqual does exclude data when numbers are low and cannot be reported with confidence. That is why our statistics may not match precisely with the total number of certain kinds of schools, colleges or exam centres.”

More generally, the spokesperson said variation in results among different schools “will be complex, including changes in cohorts, changing in teaching staff or teaching time, and the impact of the pandemic”.

They added heads of schools had to submit a “formal declaration on the accuracy and integrity of grades and processes supporting them” in the past two years.

Your thoughts