Schools should be “cautious” about introducing mentoring programmes for their vulnerable pupils because they can do more harm than good if unsuccessful, analysis shows.

A report for the Children’s Commissioner warns that despite its increasing popularity, mentoring needs a stronger evidence base before being widely rolled out to struggling pupils.

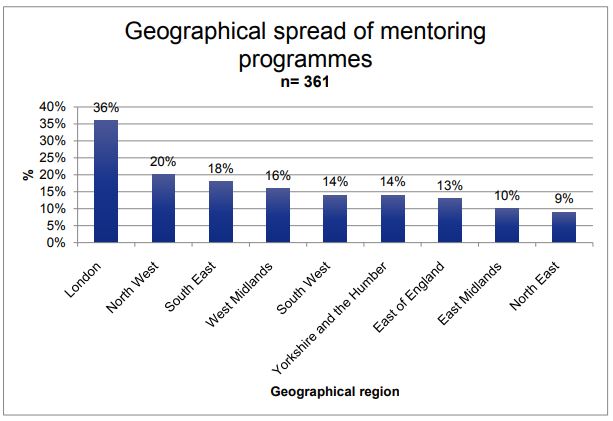

Analysts at thinktank LKMCo looked at a sample of more than 350 mentoring programmes across the country. They reviewed literature and interviewed sector experts.

The findings show “modest positive effects” from mentoring, but with considerable variation both within and between programmes.

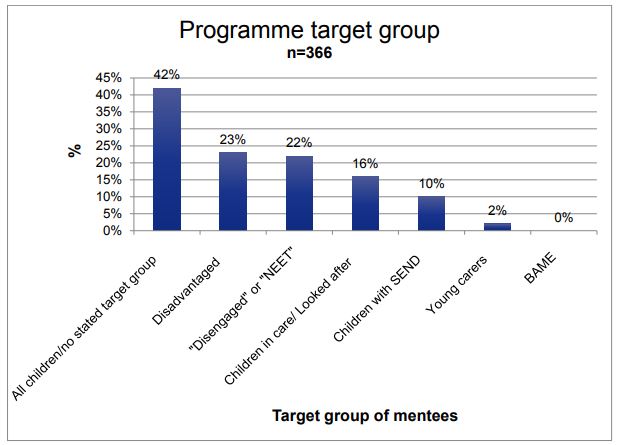

While some mentoring programmes were aimed at young adults in the community, a large proportion were aimed at pupils, and often the most vulnerable.

Pupils who were not in education, employment or training were particularly targeted – while those with special educational needs or who were young carers were the least likely to be mentored.

Nearly three-quarters of all programmes worked with pupils in year 8 to year 10, and 71 per cent with sixth form or college pupils. Primary school pupils got far less intervention.

Most of the support (73 per cent) was aimed at improving social or emotional development, while only a fifth of mentor programmes were intended to aid academic attainment.

From a review of the literature, the report concluded that “overall there are promising signs that the average youth mentoring programme has a small but positive effect on the average mentee.”

However, “there is no guarantee that mentoring will be effective and there are risks of negative effects,” it warns.

Children in care or with troubled home lives are most likely to be targeted, meaning relationships that end prematurely can be particularly damaging (Rhodes 2008; Duke et al 2017).

As such, “relationship duration” should be a goal of any mentoring programme. A previous report (De Wit et al, 2016) says the programme should last at least one year.

The report advises that school-based mentoring programmes “should be deployed with particular care when they involve vulnerable young people.”

Schools should prepare mentors and mentees beforehand through training and “clear expectations of the relationship”, and take a flexible approach to their mentoring agenda.

The mentor should allow the young person’s needs and interests to come to the fore, and also get to know their parents.

For those thinking of setting up mentoring programmes, they “must ensure they are well-versed in current evidence.”

Following that, the programmes should be evaluated as rigorously as possible, and even seek to partner with research organisations to check on their own impact.

Your thoughts