Andrew Moffat, an assistant headteacher at one of the largest primary schools in Birmingham, appears unstoppable: he is navigating a school bus down a street, dodging ladies in saris walking in the road, humming snatches of a Eurovision song, and answering a clipboard of questions I have clutched in sweaty hands.

“We are finding the most diverse street in Birmingham,” he says. “The kids know what to do.”

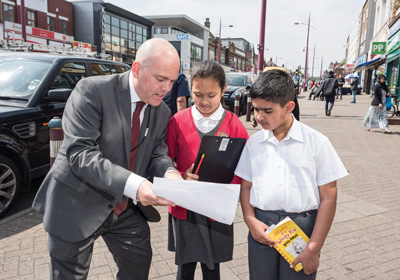

As the 45-year-old, who helps lead 750 pupils, leaps out of the bus, we already seem to be a diverse bunch: the pupils from Parkfield Community School, which is 99 per cent Muslim, have met up with a group of Church of England pupils, most of whom are white, in a joint project to ask shopkeepers in this less-affluent part of the city where they are from (fully risk-assessed beforehand).

The exchange is enlightening.

“How many languages do you speak?” asks 10-year-old Dipesh. The shopkeeper, surrounded by family members, thinks.

“Persian, Kurdish, Arabic, Urdu, Turkish, Dutch, Russian, English.” This is noted carefully.

“And do you and the other shopkeepers here help each other out?”

“Yes. We are from everywhere. Jamaica, Lithuania, Cuba.”

The pupils nod. Afterwards, Moffat explains that a group head out every week to research the diversity of the city. As anyone watching a 10-year-old writing “Afghanistan” can see, it’s as much an exercise in spelling as anything else. But it began with more than that.

I could never say I went with David. Other teachers could say they were married, and I couldn’t

“After Brexit, lots of the children asked me if they had to leave their homes,” he tells me. “The next week, we went into town to hand out flowers. I told them it would make people feel happy, but it was to show the pupils they belonged. Everyone was lovely to them. They felt really good about that.”

Teaching pupils such lessons about society through indirect, rather than direct, means is Moffat’s central strategy for delivering change. His success in teaching diversity means he delivers speeches to school conferences on almost a weekly basis on how to embed the 2010 Equality Act, which forbids any kind of discrimination, into everyday lessons.

Having risked the school trip paperwork – a barrier Moffat dismisses as only a problem if you make it one – the impact of venturing so frequently into the outside world hits like a rainbow when you get inside the school. Jaw-droppingly decorated boards, everywhere, proclaim that girls can be engineers, boys can be dancers, black is good, brown is good, white is good, yellow is good.

There is even, this reporter is delighted to see, a whole board about gingers. Two words are found across them all: “no outsiders”.

Moffat has been an outsider. At the age of six, he felt different to most boys. He didn’t like football, his friends were girls. When he was 13, he was punched by a gang because he liked Wham, and Wham were “gay” (the boys were Queen fans, not knowing Freddie Mercury was too afraid to come out).

By 16 he knew, but in 1988 Margaret Thatcher introduced Section 28, a law forbidding gay people from being discussed by teachers or textbooks. He couldn’t bring himself to come out to his family until he was 27. Never as a helper in a children’s home, or as a youth worker with gangs, or as a teacher, would Moffat answer honestly when pupils asked about himself.

“Who did you go to the cinema with, sir?” Moffat pauses during our interview. “I could never say I went with David. Other teachers could say they were married, and I couldn’t”.

While working in Coventry with challenging children, Moffat saw the TV series Little Britain introduce them to gay people through the Matt Lucas’ unforgettable Welshman, a character who repeatedly shrieks “I’m the only gay in the village”. Section 28 might have been repealed in 2003, but nothing much had changed – and to this day teachers check with Moffat if they can say “gay” in class.

Then, in 2006, he and his partner David entered into a civil partnership, and Moffat wanted finally to be honest, to set an example for other pupils who might be gay. He developed a resource called Challenging Homophobia in Schools, full of lesson plans and story books, such as two male penguins who are in love and adopt a chick. When teachers told him it was easy to preach from a predominantly white area – he should try doing it in a multi-cultural area – Moffat promptly got a job in Birmingham with majority Muslim and Afro-Carribean Christian parents. But not long after arriving, the governors said they did not want any of the materials in their school.

So he used them anyway.

“It was the wrong thing to do,” he admits. “I wanted to make that point. I was upset and angry. It was wrong.”

It was leaked to the media, and the pages of the Sunday Times, Daily Telegraph, Metro, Independent and Guardian all carried a story in the spring of 2014 of a gay teacher who was forced to resign after a parent complained they hadn’t been told their child was learning “about gay sex” – even though the story books were used not to teach about gay people, but as resources for spelling and reading.

They were right, says Moffat – those parents hadn’t been told.

So what did he do? He chose a school that was 99 per cent Muslim pupils in an area heavily affected by the so-called Trojan Horse plot to radicalise pupils (though it wasn’t one of the schools in question) and became assistant head there. His first resources went into the bin, along with its focus on lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender rights, and he produced new resources based around both the Equality Act 2010, and the government’s emphasis on “British values” such as democracy and respect for others who are different, which he called ‘No Outsiders’.

In other words, these were resources about the rights of everyone.

Does Moffat feel that being gay remains the ultimate taboo in schools? Only four of the 35 story books which No Outsiders uses refer to gay or transgender characters. Moffat is wise, and pragmatic in response.

“You know the slogan, ‘some people are gay. Get over it’? That’s no good for my parents,” he laughs, referring to gay charity Stonewall’s famous phrase.

“You’re talking about thousands of years of religious belief. You can’t just say ‘tough’.

You know the slogan, ‘some people are gay. Get over it’? That’s no good for my parents

“Instead you say ‘there are different people everywhere’, and it’s not about ‘we are right’ or ‘you are right’, but that we are helping prepare the children for all the different people they will meet. They can decide themselves.”

It’s working. The mostly Muslim governors at the school support Moffat. The parents know he is gay, and either support him, or “tolerate” it, he says.

Even I do a double-take when I see “it’s ok to be gay, or straight, or transsexual” on the walls of a primary school.

The children are also ambassadors for the No Outsiders approach to life. Since the Charlie Hebdo attacks in Paris, Moffat has produced online resources for teachers to explain hate crimes against refugees and terrorist attacks, because pupils kept asking questions. The assembly plans, which focus on the ways people pull together in the event, are more timely than ever as the children try to comprehend the recent attacks on Westminster Bridge, Manchester and London Bridge.

After the latter event, one pupil wrote to his assistant headteacher: “Perhaps if we could have spoken to him first, to the attacker, we could have explained about No Outsiders to him. Perhaps then he might not have wanted to do that quite so much.”

Instead of Prevent, maybe send in an unstoppable Moffat. Or better still, become one.

It’s a personal thing

If you could go on holiday tomorrow, where would it be to?

Stockholm is my favourite city. We’ve travelled to Stockholm loads of times for Eurovision events and parties and Sweden always do Eurovision best! Actually, Sweden should win Eurovision every year! (Although I’m very happy to go to Lisbon for the contest in 2018).

Who’s your favourite singer?

I was obsessed with Kate Bush as I grew up and that obsession never really went away. Going to see Kate Bush live in 2014 was amazing and something I never thought I’d get to do. It was wonderful to be able to share that with Kathryn [his sister] because we grew up together listening to ‘Hounds of Love’ and she was as excited as I was. I took David the second time who basically rolled his eyes and yawned throughout.

If you were stuck on a desert island with just one thing, what would you take?

My phone. Would there be a signal?

Where have you most enjoyed living? Why?

I’ve just moved house. It’s a bit of a blank canvas so it’s great to gradually make each room our own over the next year or so.

What’s your favourite film?

It has to be All about Eve. Bette Davies is an icon! “Fasten your seat belts, it’s going to be a bumpy night!”

Your thoughts