More than a third of school pupils whose first language isn’t English are fluent in the language, new government analysis shows.

The Department for Education has published analysis of data from its shortlived collection on the language proficiency of pupils with English as an additional language (EAL), which ran as part of the school census between 2016 and 2018.

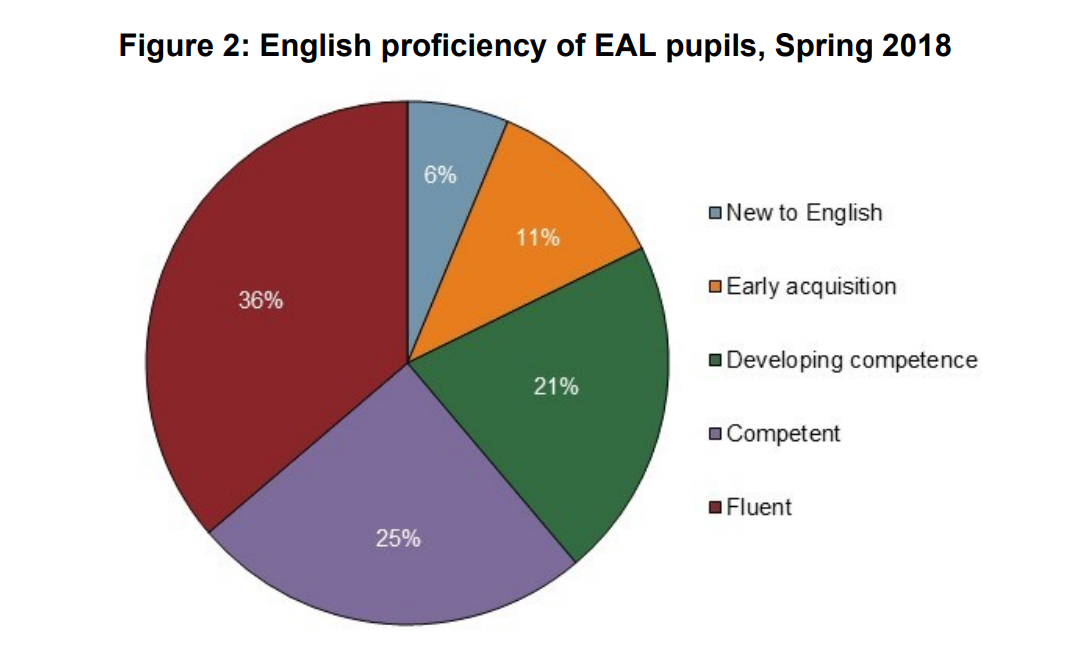

The data shows that of those assessed by schools in Spring 2018, 36 per cent were assessed as “fluent”, 25 per cent were “competent”, 21 per cent were “developing competence”, 11 per cent were in the “early acquisition” stage of learning and 6 per cent were “new to English”.

However, the data also shows big variations in the fluency of pupils depending on their characteristics.

For example, just 39 per cent pupils with special educational needs and disabilities were either “fluent” or “competent, compared with 64 per cent of those without SEND.

Language proficiency also depends on how old pupils are, and how long they have spent in an English school.

Seventy-seven per cent of EAL pupils in secondary schools were assessed as “competent” or “fluent” in spring 2018, compared to 51 per cent of those in primary schools.

And pupils who had been in an English school for five years or more were more likely to be assessed as competent or fluent in English (80 per cent) than pupils who had been in an English school for between one and four years (40 per cent).

Deprivation also has an impact. Seventy-three per cent of pupils living in the least deprived areas of England were assessed as “competent” or “fluent”, compared to just 59 per cent of those living in the most deprived.

And the proportion of pupils with a high level of proficiency also varied geographically, with 54 per cent either “fluent” or “competent” in the north east and north west, compared to 65 per cent in London and 66 per cent in the south east.

The proficiency in English data collection was introduced in 2016, alongside more controversial moves to collect data on pupils’ nationality and country of birth.

But it was scrapped two years later following a fierce backlash against the nationality and country of birth collections, prompting concerns that the DfE was “throwing the baby out with the bathwater”.

The data release comes after research by The Bell Foundation, a language education charity, found that it takes two-thirds of pupils who start in reception at the lowest level of English language proficiency more than six years to progress to the highest levels of proficiency.

However, the charity has warned that funding is only available to support these learners for three years, and that more specialised support is required.

Professor Steve Strand, from the University of Oxford, who was the lead research author on the Bell Foundation’s project, said: “The fact that, even six years after starting reception as new to English, only around one-third of pupils have transitioned to competent or above, is concerning.

“This suggests that while many pupils have achieved oral proficiency in English, relatively few gain academic linguistic proficiency in this timeframe.”

Your thoughts