Schools in the biggest training hub in the north-west for the new relationships and sex education curriculum speak to Jess Staufenberg about getting it right – and avoiding bad speakers

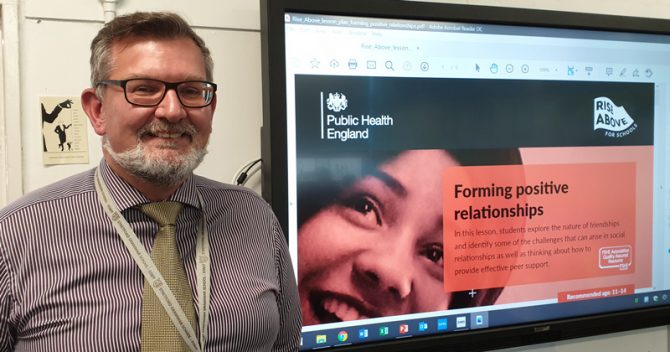

So what’s a positive relationship?” Several hands shoot up from the sea of year 7s during their Friday afternoon PSHE lesson. “One that’s give and take,” says one with confidence. “You’re kind to each other,” explains another. Ian Nicholson, assistant head and relationships and sex education (RSE) lead at Stretford Grammar School in Manchester, towers above them with a big benevolent beard. “And why are positive relationships important?,” he presses. More hands shoot up. At the front of the class is a slideshow emblazoned with Public Health England branding and a label saying PSHE Association Quality Assured Resource.

These year 7s may not know it, but they’re now in a legally compulsory lesson that schools must deliver. From this September, relationships and health education must be taught at secondary and primary level, and sex education at secondary level. Due to coronavirus, schools have a grace period until next September to get their RSE curriculum completely sorted, but it’s already compulsory: academy, local authority, independent school or otherwise.

Ofsted will be commenting on the curriculums if inspections resume in January, but judgments won’t be impacted until the summer term. That’s when things get serious. Schools failing to teach about LGBT relationships, for instance, risk a ‘requires improvement’ grade.

The calm demeanour in the year 7 class belies a colourful run-up to the curriculum’s launch. After two decades, the non-statutory Sex and Relationships guidance from 2000 was scrapped and a consultation launched on a statutory Relationships and Sex Education curriculum (note the switch in emphasis). In February last year the consultation report revealed 64 per cent of respondents (of whom two-fifths were parents or grandparents) deemed the content for secondary schools not “age appropriate”, with a similar proportion at primary level. But the government firmly responded that “pupils should be able to understand the world in which they are growing up, which means understanding that some people are LGBT […] and that the law affords them and their relationships recognition and protection”.

Those twin focuses – the law and relationships (rather than sex) – appears to have been the government’s rather nifty way of helping schools deliver the most inclusive and contentious content without putting staff too much at loggerheads with communities. After minor amendments, including that schools themselves can decide when to introduce LGBT relationships, the curriculum was rolled out by “early adopter” schools last academic year before beginning in earnest this year. Getting it right is crucial.

It may seem a lifetime ago but only last summer the news was filled by weeks-long protests from some Muslim parents at Anderton Park and other primary schools in Birmingham over LGBT content. Since then, a culture war about transgender rights has also peaked to frenzied levels. Such divisive arguments need to stay outside the gates of Stretford Grammar, not only since 13 pupils are transgender, but because the school is part of the Alliance for Learning teaching school, run by the Bright Futures multi-academy trust. The alliance recently won £150,000 of Department for Education funding to become the biggest RSE training hub for 400 schools across the north-west.

Nicholson says at his school, half of whose pupils have Asian heritage, including Muslim and other faith backgrounds, good relations with the community about the new curriculum were built by following the government’s guidance that schools should consult and share resources with parents to the letter. “Schools have been scared to go near some of this because of what happened in Birmingham. It was so big in the media and so it was about helping schools understand what they can say. Parents just want a voice.”The results seem to speak for themselves – out of 900 pupils, only one withdrew from RSE. “It’s about explaining, this is the law. We’re not trying to present an opinion.”

This focus comes straight from the DfE guidance for secondary schools, which has an entire section called The Law. It states “pupils should be made aware of the relevant legal provisions” around discussed topics, listing 14 examples, including gender identity, marriage, pornography, abortion, “sexting” and female genital mutilation. Getting teachers up to speed on the law in these areas has formed the bulk of training, explains Nicholson. It’s a good thing too, since a survey in July last year found almost half of teachers said they lacked the confidence to deliver the new curriculum.

To increase confidence among staff and pupils, Stretford Grammar has also given responsibility for delivering the curriculum to every pastoral head of year, rather than leave it to a roaming PSHE lead. “It means the pupils in each year get really good, strong relationships with their heads,” says Nicholson, and trust and confidence have increased as a result.

Aside from the useful focus on the law, the focus on relationships also seems to have a curious side effect. Under the new guidance, parents still retain the “right to withdraw” their children from sex education lessons, but they do not have the right to do so from relationships education. The question then is – where does the relationships education curriculum end and the sex education curriculum begin?

Michelle O’Neill, PSHE lead at Wellacre Academy, a boys’ school in Trafford, which also belongs to the Alliance for Learning teaching school, explains the decision belongs with schools. “It’s up to the school what they classify as the sex element – the DfE haven’t stated what that is.” As a result, “for many school leaders that’s been the biggest challenge – what they defined and agreed was the sex element and what was the relationships element, and then how to manage those withdrawals”. You can imagine the scene: a parent wishes their primary child to be removed from a lesson which mentions same-sex relationships only to be told it’s not sex education but relationships education.

But like Nicholson, O’Neill’s school, which was an “early adopter” of the curriculum, has received no complaints from parents since rolling it out. How little of the new curriculum can be classed by a school as sex education only suitable for secondary level is evident. “I found literally three lessons across year 9 and 10,” says O’Neill – they deal with pornography and contraception. Even consent is classed under the relationships education framework, as it’s about healthy intimate relationships.

With such room for manoeuvre, getting advice from the Alliance for Learning network seems important. Lisa Fathers, its director, is jubilant about the new curriculum and says 185 out of the 200 schools in the first phase of training across the north-west have engaged, and she hopes the remainder will follow suit. But “there are some local authorities where only half the schools seem to have signed up”. Her only other concern is that funding runs out in March 2021. “If we had more funding, what we’d do is provide another year’s support for them, to make sure they can really embed this.”

Those schools that don’t get involved in time with the training hubs could miss out on perhaps their most important offer – a vetting system for all the speakers requesting to talk to pupils. “As a PSHE lead, you get bombarded with emails,” Nicholson explains candidly. “I get about eight a day. It might look really good, but you don’t know anything about them and that’s when I ask the group and say, ‘OK, who is this?’”

It’s an issue that exploded into the news last weekend, as the government released additional non-statutory RSE guidance warning schools should “not work with external agencies” which over-zealously promote gender reassignment or hold “extreme political stances”. Nicholson recalls being warned by colleagues in other schools against one speaker. “It was quite a difficult conversation to have. So it’s really important you have that network who you can rely on.” Now the Public Health England materials in the year 7 class, with the visible quality-assurance stamp, make more sense.

So, there are challenges ahead. Mark Edmundson, head of school at Elmridge Primary in Trafford, also in the Alliance for Learning, has been prompted by the new curriculum to audit the books available to pupils and found very few represented non-traditional families. “We realised we didn’t have anything that showed families with one parent, or two mums or two dads, so when we replace those books we’ll be looking for that.” No doubt Edmundson will use the network to get good recommendations. For the first time, the school has also introduced two new units of work, on homophobia and bereavement, and a new half-unit on “challenging stereotypes”. As a primary school head, he must strike a careful balance.

But across the board, schools are clear – the guidance has prompted them to reflect and refresh an area of the curriculum that had grown tired, or pulled up those schools that avoided it. “I just think it’s massively important pupils understand the environment they’re growing up in. Society has changed a lot in the last 20 years and we need to educate them about that,” says Edmundson. “What’s important is that we review this every few years – so we stay responsive to how society is changing.”

Your thoughts