The official in charge of regulating schools’ admissions arrangements has published her annual report.

Shan Scott, the chief schools adjudicator for England, said her report gave an overall impression of an admissions system “that as a whole works effectively in the normal admissions rounds, and in those rounds, the needs of vulnerable children, and those with particular educational or social needs, are generally well met”.

However, the report also raises some concerns about some aspects of school admissions, and shows how national trends are affecting statistics in this area.

Here are six interesting points we pulled out.

1. Variation requests soar as primaries seek to downsize…

Admissions authorities wanting to make changes to a school’s admission arrangements have a chance to do so every year through a statutory process that requires advance notice and consultation.

However, in certain circumstances, they can apply to the Office of the Schools Adjudicator (OSA) for permission to make variations to arrangements that are already determined.

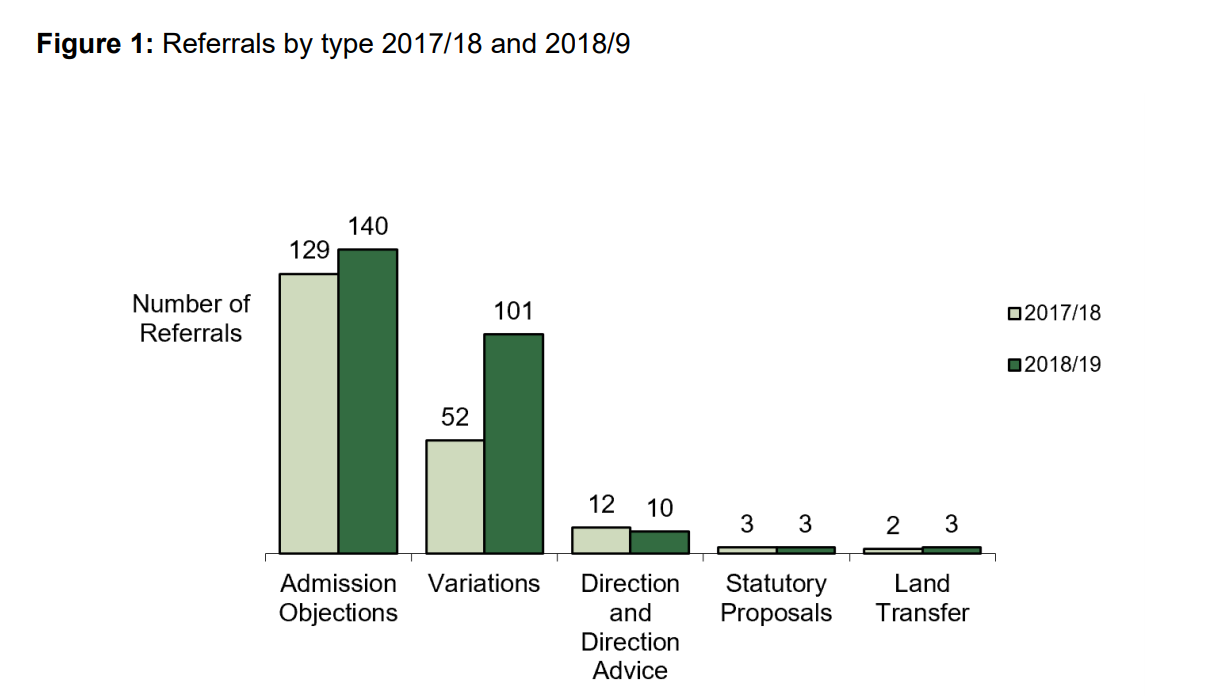

In 2018-19, the number of referrals to the OSA of proposed changes to admissions arrangements almost doubled, as more and more primary schools sought to deal with falling pupil numbers.

A baby boom from the early 2000s is currently in the process of making its way into secondary schools, leading to a drop in the number of primary-age pupils.

Scott said the OSA received 101 referrals over variations in 2018-19, up from 52 the previous year, and said a wish to reduce the published admission number (PAN) in primary schools was the main reason for seeking a variation.

2. …but some councils may be misusing the process

Scott raised concerns in her report that requests for variations of pupil numbers are being made when they could have been done through the proper statutory process.

“When a PAN is reduced by means of a variation there is no consultation and no scope for objections,” she said, adding that a variation should be “a last resort”.

“I am troubled, in this context, that in six cases we have been asked to approve variations to PANs for the same school year on year. This suggests, at the very least, that it should have been possible to plan ahead and consult on a reduced PAN.”

3. Home education rises again

The 152 local authorities responsible for education in England reported that 60,544 pupils were electively home-educated as at March 29, 2019.

This represents a 12.8 per cent rise on the number reported at the same point the previous year: 52,770.

The figures are likely to cause alarm among ministers, who have expressed concerns about the number of pupils being removed from school rolls and have previously touted plans for a register of home-educated children.

According to Scott, many councils continue to have concerns that “some parents may opt to educate their child at home but not actually be able to provide education which fully meets the child’s needs”.

4. Grammar school objections motivated by ‘desire to change the law’

Of the 140 objections to admissions arrangements received by the OSA in 2018-19, 58 related to the arrangements of 36 different grammar schools.

The objections were varied. Some objectors “did not believe that priority should be given to children entitled to the pupil premium”, while others said their local school was not doing enough to admit disadvantaged pupils.

In her report, Scott said her office continues to deal with objections motivated not by a belief that a school’s admission arrangements break the law, but by “a desire to change the law relating to admissions or the code”.

“I think it is right that I say now that in the past few years it has particularly been grammar schools that attract such objections. I recognise that many people hold strong views about grammar schools and we receive objections from those who support selective education and from those who oppose it.

“However, the role of the adjudicator is to test arrangements against the law and the code as they stand.”

5. Faith school refused looked-after child

Under the current admissions code, faith schools are allowed to prioritise children of their own faith who are not looked-after over looked-after children of a different faith or no faith at all.

In one case referred to the OSA in 2018-19, a faith school with more applicants of its own faith than it had places had refused a place to a looked-after child.

“It gave priority to children of the faith and as the looked after child was not of the school’s faith, the child could not be offered a place under the school’s oversubscription criteria,” the report said.

However, the local authority responsible for the child sought a direction from the OSA to force the school to take them, and the OSA ruled against the school.

Scott said such cases are “likely to be rare”, but said she wanted to make clear that “in relation to a looked after child the only ground for the adjudicator to decide that the child should not be admitted is if such admission would seriously prejudice the effective use of resources or provision of education”.

“This is a high threshold,” she added.

6. Rules for all-through schools cause ‘complications’

Because of the way the law currently works, pupils who move from an all-through school to another school in year 7 cannot be removed from the register of the all-through school at the end of the summer term of year 6.

According to Scott, this means the child remains on the register of their previous school until September, meaning the child is “effectively holding two places”.

“This can mean that other children cannot be offered a place at a preferred school – either the all through school which does not know it will have a vacancy or the secondary school which is expecting the child to transfer,” the report said.

This set-up adds to the “complications of co-ordination” and “affects schools and parents and children alike”.

7. GDPR confusion causing problems for looked-after children

When schools are oversubscribed, admissions authorities have to prioritise current or former looked-after pupils.

However, a number of councils told the OSA that they had problems establishing whether a child actually was looked after.

Sometimes this happens because the child was looked after in the past or by a different authority, and their status was not made clear on their school application.

One authority reported that “difficulties only relate to obtaining clear verification of LAC/PLAC status from other authorities due to GDPR and staff availability”.

But Scott said she found it “difficult to understand why the GDPR would cause problems in the necessary sharing of information about a child’s looked after or previously looked after status”.

The GDPR or general data protection regulations place duties on organisations to process personal information fairly and lawfully, and “are not a barrier to sharing information where the failure to do so would cause the well-being of a child to be compromised”, said Scott.

Your thoughts