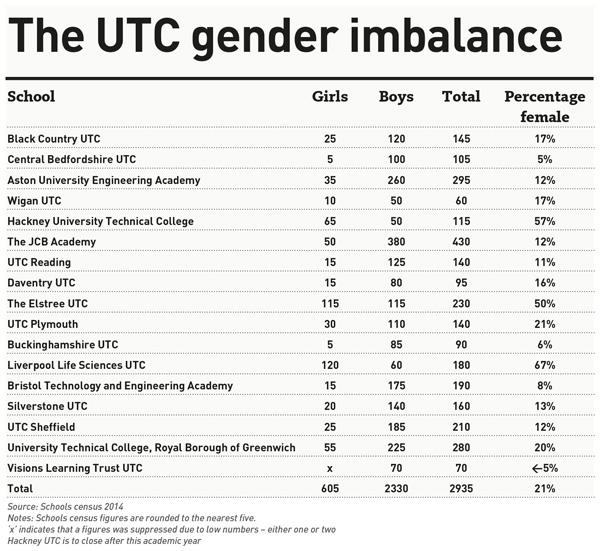

As few as one in 20 students at some university technical colleges (UTC) are female, analysis by Schools Week shows, prompting claims that the current model is not the best way to help girls to get into traditionally male-dominated industries.

The news comes after Education Secretary Nicky Morgan said that the lack of women taking STEM (science, technology, engineering and maths) subjects was one of the reasons for the pay disparity between men and women.

Analysis of the 2014 schools census by Schools Week shows a paucity of female students at many UTCs – most of which offer courses in areas such as engineering and other technical fields.

In total, just over one in five students at a UTC is female. But the gender split varies considerably across institutions, with girls making up more than half the pupils at three UTCs. However, four UTCs have proportions in single figures.

The three UTCs with at least 50 per cent girls on roll specialise in life sciences and healthcare, digital media production, and supporting technical skills for the film, theatre and visual arts industries. One of these UTCs, in Hackney, is set to close at the end of the academic year.

Speaking on Monday at the Wealth Management Association, Education Secretary Nicky Morgan, who is also Minister for Women and Equalities, linked the low number of girls studying technical subjects and the gender pay gap.

“Too many young women embark on less well-paid careers than their male counterparts.

“We’re working to improve careers advice in schools and colleges, and we’re encouraging more girls to take the STEM subjects that lead to better-paid jobs.”

Responding to the new figures, Professor Alison Wolf of King’s College London warned that even “well-equipped” UTCs might not be the way to get more girls into these subjects.

“Engineering is genuinely desperate to attract more talented women. But it is going to be difficult to persuade many 14-year-old girls to opt for a boy-dominated specialty and boy-dominated classrooms for the rest of their school lives.

“Governments have tried advertising campaigns, and have now tried well-equipped UTCs. Keeping girls’ options open, so they can make choices when they are more mature, strikes me as a better bet.”

The UTC model is currently being expanded, with the number of students attending a technical college set to grow from about 2,300 last year to more than 8,000.

A spokesperson at Baker Dearing Educational Trust, which promotes the UTC model, said: “There is an urgent need to attract more young women into STEM careers and all UTC principals are committed to this. However, the shortage of girls in engineering and associated areas has been a problem for decades and needs a joined-up approach if we’re to make a difference.

“UTCs work with lots of organisations to tackle the issue such as the WISE [Women in to Science and Engineering] campaign which is running workshops across the UTC network, and the government’s Your Life campaign.”

Central Bedfordshire UTC has 5 per cent female students – which it has acknowledged is not as many as it would like.

Headteacher Lesley Glover said: “By coincidence we have been meeting this week with a nationwide engineering employers’ organisation, and our sponsors Bedford College, and among the topics of conversation was how we can all work together to attract more young women into engineering education and careers.

“This is a much wider issue than UTCs.”

Phil Lloyd, principal of the Liverpool Life Sciences UTC, which had the highest proportion of female students at 67 per cent, said that it offered something to girls “unsatisfied with the status quo” of their previous schools.

And this doesn’t help…

A report presented by the Royal Society outlining its vision for science and maths education was challenged this week due to its under-representation of girls.

Presented during a fringe event at the Liberal Democrat party conference in Glasgow last week, the report “Vision for science and mathematics education” summarises the society’s recommendations for science and mathematics education over the next 20 years, including how to encourage girls to join STEM courses.

An audience member at the event criticised the report after bringing to light the fact that the front cover only included pictures of boys, and of the 17 people shown in photographs throughout it, just three were girls.

“One girl is doing biology and we can’t see what the other two are doing,” the audience member said.

Commenting on the report, Dr Allan Colquhoun, a panel member at the event, said: “I agree that we need to be very careful in our portrayal of gender when illustrating STEM careers. One particular issue is the cliché of showing female engineers in hard hats in ‘dirty’ environments.

“Whilst the ‘Vision’ addressed the gender issue I don’t feel it had sufficient emphasis. Gender is the biggest issue in the STEM area. We are not accessing nearly half of the potential workforce.”

In defence of the report, Professor Dame Julia Higgins, chair of the society’s education committee, said: “The Royal Society is very aware that more girls need to be encouraged to take science subjects and this is a point made very strongly in our recent report.”

The UK has one of the worst records for recruiting women into engineering in the developed world. Only 7% of the engineering workforce is female. As UTCs prepare more young women for engineering degrees and apprenticeships, society’s perceptions will start to change.

Great that so much publicity to this issue. Vital that we work together to attract more girls to STEM. UTCs part of the picture.

People underestimate the complexity of issues in widening access to STEM for girls in this age group (14-19). The UTCs were not prepared at the start but many UTCs have now developed programmes and are devloping the expertise to grow the numbers of girls applying. This is a long term project – there is no silver bullet.