Not a single failing school became an academy less than nine months after an inspection in at least 26 local authorities over the past three years, Schools Week can exclusively reveal.

Schools have been unable to secure takeovers due to a lack of sponsors, complicated PFI contracts, and even because regional schools commissioners sent academy orders through late – sometimes as much as a year after Ofsted first inspected them.

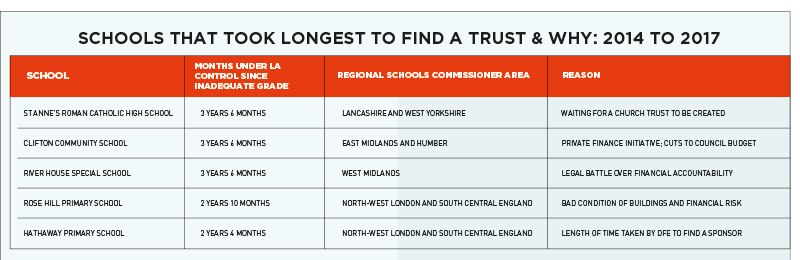

Freedom of Information requests to over 70 councils show that 35 schools took longer than two years to convert, even though the government aims to make turnarounds in nine months or under.

Only 11 councils managed to convert all their failing schools within this timeframe.

In several cases, schools were left so long they were reinspected and received higher grades, leading one policy expert to argue that their academy orders should be revoked.

A lack of suitable sponsors caused problems among 11 of the councils that failed to turn their schools around in time.

Wirral council said its RSC Vicky Beer took more than two years to find a suitable sponsor for two schools. The schools are now due to join a trust, though this has not yet taken place.

Woodford Primary School in Plymouth waited almost a year before a sponsor could be found that was “acceptable” to the government, while Gloucestershire council said it had been working hard with its RSC, but that it lacked suitable academy sponsors in the area.

Buckinghamshire council similarly cited “lack of sponsor capacity” for delays of between one and two years across six of its ‘inadequate’ schools – and is now visiting multi-academy trusts in other local authorities to “widen and maximise opportunities”.

Faith schools are particularly at risk of hold-ups due to an agreement between the church and the Department for Education that only trusts accepted by the church can take ‘inadequate’ faith schools over.

St Anne’s Roman Catholic High School in Stockport waited three and a half years to convert after it was rated ‘inadequate’ in October 2014 over teachers’ “low expectations”. Salford diocese needed to find a “suitable school” to sponsor St Anne’s via a new trust, but was delayed.

The Sir Thomas Boteler Church of England School in Warrington also waited almost three years “due to the time taken to create” the Challenge Academy Trust, according to the council.

Another faith school, St Joseph’s Roman Catholic primary, in west Yorkshire, will have been delayed by two years because there was “no church multi-academy trust” to sponsor it. This trust is “now being established” and the proposed takeover is for October this year.

The structure of headteacher boards, which help approve sponsorship changes, does not improve the speed of decisions.

Pam Tuckett, a partner at accountancy firm Bishop Fleming, pointed out that headteacher boards often ask for additional information before making decisions, but the infrequency of the meetings means the process can go “backwards and forwards quite a few times” over a long period.

Commissioners are also sending out academy conversion orders late, councils warned.

In Southampton, Dudley and Surrey, RSCs only sent an academy order after many months elapsed since Ofsted published its report on a school.

At Woodside Primary School in Dudley, an “academy order was not received until 12 months afterwards” and it did not convert until almost two years after it was first put into special measures.

There was also five-month delay on an order for another school, Ham Dingle Primary.

In Surrey, an order also arrived nearly six months later, and Southampton council waited for an academy order “for many months” without specifying how long.

North Tyneside council added that its RSC only appointed an interim executive board to one of their schools after 13 months, and that this board took a further 14 months to sort out the transfer.

This “created instability for students and staff”, said a spokesperson.

One consequence of the slow drift towards academy status is that 11 schools subsequently came out of special measures even without conversion.

Foxfield Primary School moved from the bottom grade in May 2014 to ‘outstanding’ one year and four months later, but still converted to an academy, three years after the inspection. Three other schools moved from ‘inadequate’ to ‘good’ while waiting.

John Fowler, a policy manager at the Local Government Information Unit, pointed out that the education secretary has the legal power to revoke an academy order in case it closes instead.

They should consider revoking an academy order when a school is improving without converting, “especially when a multi-academy trust cannot be found,” he suggested.

Another school to improve its Ofsted grade was the Sholing Technology College in Southampton, which has been waiting for a new sponsor since it was rated ‘inadequate’ in 2016, and moved to ‘requires improvement’ last year.

Southampton council said the delay was due in part to a “lack of effective management” by its RSC Dominic Herrington.

Herrington, who oversees south London and the south-east, was the best-performing commissioner in 2015-16 according to the government’s key performance indicators for that year, including for the percentage of schools issued with an academy order and converted to academies.

If a school is judged to be progressing towards expected educational standards before it converts to an academy, then the secretary of state has the power to revoke the academy order and will consider this on a case-by-case basis, according to the Department for Education.

A spokesperson added the government is investigating “what can be done to improve conversion times.” They added the average time for school rates ‘inadequate’ to convert was 8.5 months, between April 2016 and March 2017, but the DfE recognised the process could be faster.

Case files

Swindon: Not one school converted on time

Four maintained schools in the Wiltshire local authority were graded ‘inadequate’ between 2014 and 2017. Three took more than nine months to convert and the fourth remained with the council.

Ruskin Junior School was blasted by inspectors in 2014 for poor pupil behaviour and low pupil progress, especially among boys. But the school only converted 16 months later, because the Blue Kite academy trust had to wait to “get their sponsor status confirmed”, the council claimed. This is the only school now with a new trust.

Both Abbey Park School and St Luke’s special educational needs school have waited around 18 months to convert. Restrictions on land use brought things to a halt at Abbey Park, and though these issues are now resolved, a sponsor is yet to be found. Funding issues at St Luke’s have delayed its move over to proposed sponsor the White Horse Federation.

The final school, Bridlewood Primary, came out of special measures just six months after inspectors noted declining standards. A new headteacher has a “very clear idea” of school improvement, and it was rated ‘requires improvement’ in January. The school is not now converting.

Doncaster: Four out of eight ain’t great

Four maintained schools remained with the Doncaster local authority for more than nine months, while four were converted on time.

When Edlington Victoria Primary School dropped from ‘good’ into special measures three years ago after leaders failed to “arrest a decline in standards”, the local authority asked for help from a nearby school. That school, the ‘outstanding’-rated Hill Top Primary, eventually applied to become the Exceed Learning Partnership.

The whole process took more than two years. During that time, the new executive headteacher managed to return the school to a ‘good’ grade in just a year and a half, before it finally converted and joined the new trust.

The same process was used with Scawsby Rosedale Primary School, which eventually joined another ‘outstanding’ LA school to become a trust after a 23-month wait.

Morley Place Junior School and Waverley Primary School were less successful. Both were rated ‘inadequate’ in 2015 and remained with the council for 13 months before joining the Wakefield City Academies Trust. WCAT subsequently announced plans to give up all 21 of its schools last September, leaving the two to find new homes all over again.

However, the remaining four schools all converted within the timeline, with one, Denaby Main Primary, moving to Astrea Academy Trust in a rapid four months.

Croydon: One step ahead of the game

No schools had delayed conversions in this south London patch – mainly because they’d already started converting when Ofsted arrived.

Ryelands Primary was rated ‘inadequate’ in 2014 after inspectors found teachers were giving work that was “too hard or, more often, too easy”. But Croydon said the process of academisation had already begun, and two months later the school was with Oasis Academy Trust. In 2017 it was rated ‘good’ with ‘outstanding’ leadership, and there was special praise for the trust for holding leaders to account “in an exceptionally thorough and robust manner”.

This timely transfer was matched by two other primary schools, with academisation already underway during the inspection.

However one ‘inadequate’ school was not converted at all. The Minster Junior School fell from ‘outstanding’ in 2010 to the bottom grade four years later because “too many pupils significantly underachieved”, but it remains with Southwark Diocese.

Two years later, the school was judged ‘requires improvement’. Inspectors noted the headteacher had “worked tirelessly” since the last inspection and the school is likely to keep improving.

Other councils have also reported church schools being allowed to stay with their diocese. For instance, Knowsley council simply reported of one of its ‘inadequate’ Catholic schools that “Liverpool Archdiocese do not academise schools”.

Public Accounts Committee launches inquiry into academy conversions

The parliamentary public accounts committee will grill officials from the Department for Education on whether converting schools to academies delivers “the right results” for pupils and taxpayers.

In particular, ministers will need to explain why it has taken the DfE longer than expected to convert underperforming schools into academies, despite their arguments these schools benefit the most from the change.

The inquiry, which will be held on May 2, was prompted by the National Audit Office’s report in February which noted that two thirds of maintained schools rated ‘inadequate’ took longer than ‘nine months to open as academies.

The NAO estimates that 37,000 pupils were in maintained schools in January which Ofsted had put into special measures more than nine months previously, but which “had not yet opened as academies”.

That NAO also noted “considerable regional variation” in the number of sponsors nearby to underperforming schools. In a damning analysis, the NAO claimed that while the DfE was offering grants to help sponsors take on more schools, there was no evidence the DfE had actually “assessed whether this funding is helping”.

There’s little chance of the DfE rescinding academy orders – ministers are still committed to a wholly academized system despite 100% academization by 2020 not being enshrined in law.

If inadequate schools can improve before becoming academies, then why does the DfE still promote the more expensive option of mandatory academization for such schools? Could it be ministers are more driven by ideology than evidence?