Ministers face swapping a “crisis of quantity for crisis of quality” in teacher recruitment after providers were told to accept more applicants.

Susan Acland-Hood, the DfE’s permanent secretary, asked teacher trainers in April to “respond” to a “high level of interest” by considering more offers and expanding training cohorts, shows a letter seen by Schools Week.

The government is under pressure to deliver on its flagship promise to recruit 6,500 more teachers.

No provider will turn away good-quality applicants on a whim

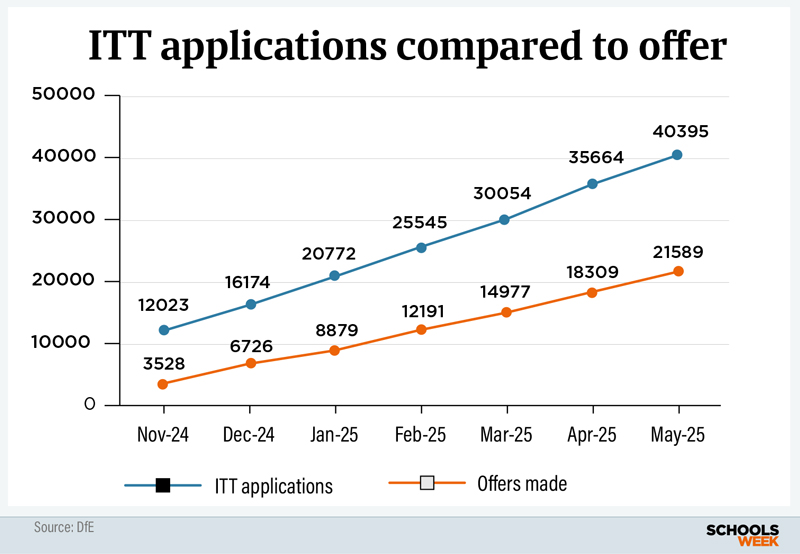

Recent figures show applications to train as a secondary school teacher are 12 per cent up on last year.

But Acland-Hood told providers that the “number of candidates who have received a rejection remains high”.

She pointed to an 11 per cent rise in domestic secondary applicants this year, while offers had risen by only 5 per cent.

“I would like to encourage you to consider whether you could increase your offer-making and take a larger number of trainees on to your course,” she urged providers.

Nine in 10 ‘concerned’ about quality

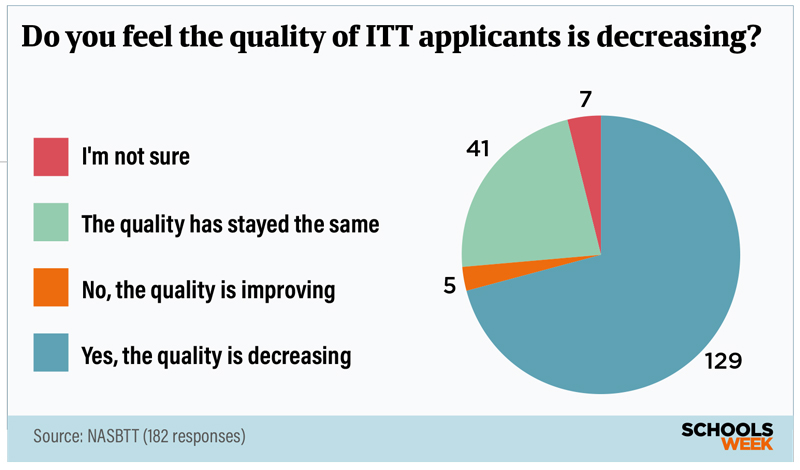

But a snap poll by Schools Week of 182 school-based teacher training providers (SCITTs) this month found nearly 90 per cent “concerned” about applicant quality.

More than 70 per cent said quality was “decreasing”, while 22 per cent said it remained the same.

Emma Hollis, the chief executive of NASBTT, which represents SCITTs and which ran the poll, said pressuring trainers into accepting unsuitable applicants “risks swapping a crisis of quantity for a crisis of quality”.

Schools Week commissioned the poll after the issue was flagged in a recent NASBTT member survey.

Eleven of 34 providers involved raised specific concerns about “deteriorating applicant quality and rising support needs”.

One said there were “no phases or subjects where we are seeing a steady supply of sufficient high-quality applicants”, adding primary was “particularly concerning”.

One SCITT said it was receiving “huge” numbers of maths applicants, but “the quality of candidates is very poor”.

Another said applicant numbers were “similar to two years ago”, but the quality was “sometimes lower with qualifications from abroad or degrees in different subjects so takes a lot of time to check subject knowledge meets our require[ments]”.

Hollis said concerns focused on “qualifications, subject knowledge, and candidate preparedness”.

One ITT provider suggested a lack of financial support and the reputation of teaching could be factors.

However, it appears to be a different picture among university training providers.

James Noble-Rogers, the executive director of the Universities Council for the Education of Teachers (UCET), said anecdotal reports showed the quality of applicants “is actually increasing this year”.

Drop in higher degrees

While it does not necessarily dictate teacher quality, the percentage of postgraduate trainees with a 2:1 degree or higher has fallen from 74 in 2023-24, to 72 per cent of those starting training in September – the lowest level in a decade.

Meanwhile, the percentage of new trainees with an “other degree class” made up 7 per cent of those who started training this September, up from 6 per cent last year and between 3 to 4 per cent for ever year before that since 2015.

The DfE said “other” degrees included those below a 2:2 and those that did not fall into the standard UK classification system, such as overseas degrees.

Hollis said any pressure on providers to “extend offers outside of their usual decision-making frameworks” could mean “diluting the quality of training” as well as putting strain on mentors and other staff, and “potentially affecting retention rates over time”.

‘Overwhelming schools’ concern

“No provider will be turning away good-quality applicants on a whim. The danger is that if pressure is put on to increase offers on an arbitrary basis…you’re asking providers to accept somebody that they would otherwise have felt wasn’t right for the profession.”

One SCITT, which did not want to be named, said while it was “flexible and optimistic” about applicants and their suitability, it was “cautious about not overwhelming” schools with high numbers of “trainees who need significant additional support”.

Hollis said that any growth in recruitment must be matched by the ability of schools and providers to maintain the quality of training, mentoring and support.

“School capacity – which is already stretched – must be a key consideration in any strategy for expansion.”

NASBTT, responding to Acland-Hood, said many providers reported a “significant increase” in applicants for the postgraduate teaching apprenticeship – particularly for primary spots, which do not have a postgraduate bursary.

However, the capacity of primaries to support apprentices – who are paid on the unqualified teacher pay scales at least – “remains extremely limited”.

“As a result, providers are having to reject many otherwise promising applicants where suitable employment cannot be secured,” Hollis said.

“This mismatch between candidate expectations and employment realities is an area where a broader conversation would be valuable.”

Long wait for response’

But Acland-Hood was also critical that about 11 per cent of candidates waited more than 30 workings days for an application response.

“The longer a candidate waits for a decision, the more likely they are to drop out of the recruitment process,” she said, urging providers to respond “as quickly as possible”.

Hollis said NASBTT has investigated the reason for the lag, and believes providers often communicate with trainees outside the application system.

Acland-Hood also revealed the government would soon trial a new tool that allowed providers to find local applicants who had been rejected.

This would help “ensure that promising candidates are able to secure places even if their first-choice institutions cannot accommodate them”.

Paul Stone, the chief executive of Discovery Schools Academies Trust, said applicants tended to have good subject knowledge, but many lacked “practical knowledge” and appeared “unprepared to be adult learners”.

“They are often waiting for somebody to tell them what to do…There’s no self-led leadership in them. They don’t have those skills.”

He also said financial incentives meant people choosing certain subjects “because it’s got a bursary, not because they’ve got a love of [the subject]”.

Covid consequences

Annie Gouldsworthy, the director of ITT at The King Edward’s Consortium in Birmingham, said there had been “no decline in the calibre of applications” at her SCITT.

But since Covid disrupted and stalled some university experiences, trainees sometimes needed more support with the “more outward-facing aspects of teaching”.

This involved “interpersonal communication and coping with workload/time pressure”.

Some providers have called for the reinstatement of a fully funded subject knowledge enhancement (SKE) programme to ensure that teachers were well-prepared and passionate about their subjects.

SKEs help trainees top up their knowledge on specific subjects before starting their training, but the government recently cut the number of courses from 10 to five subjects.

Gouldsworthy said “negative rhetoric” had “dominated the conversation for too long when it comes to the so-called ‘quality’ of applications” and teaching in general.

She said a positive change in recruitment could only happen if the profession was given due credit and celebrated its potential as a rewarding career. That included making it “financially rewarding”.

The DfE was approached.

Politicians do not want to pay teachers as professionals. They do not see teachers as professionals. This years 4% says it all. Completely inadequate in light of the recruitment and retention crisis. They still do not get it, because so many do not send their children to state schools.

The total applicant to offer ratio can be misleading. Simple primary/secondary breakdown of ratio is better but still misses the fact that some subjects such as music often only attract applicants with qualities that provide high applicant to offer ratios whereas in other subjects the range of backgrounds and subject knowledge is much wider and produces a much greater ratio.