There’s a huge difference in the attainment of older and younger pupils in the same year, and it’s too often misdiagnosed, says Stephen Gorard

It is well known that summer-born pupils leave school with lower grades than their peers, but research has now shown that they are also diagnosed by schools with special educational needs at a significantly higher rate than the older children in their year. It is time government took action to address both problems.

In England, the oldest child in a year group is born on or near September 1, and the youngest up to 12 months later, until August 31 the following year.

How old a child is relative to the rest of their year group has been strongly linked to attainment, later-life outcomes, and wider personal development.

In England, 49 per cent of summer-born children who start school in September having just turned four achieve a “good level of development” in their first year, compared with 71 per cent of autumn-born pupils, who are nearly five when they start.

The younger children in any cohort are less likely to pass the entrance test for a grammar school, are entered for fewer examinations, and are 10 per cent less likely go to university. By the age of 18, they have had 12 or more years as the youngest, least mature, and maybe the smallest person in their year. The summer-born pupils are less likely to be picked for competitive sports, more likely to be bullied, and to have lower self-esteem. Age-in-year clearly matters.

These differences in outcomes cannot be explained by most other characteristics. Younger children are no more likely to be boys, or from less-educated families, specific ethnic groups, or poorer areas, for example – all of which are also factors related to differences in attainment. They are, however, more likely to be labelled as having SEN.

Children with lower results at school tend to be considered for SEN labelling

New research presented at BERA 2017 showed that a pupil’s precise age ought be given more consideration in identifying ‘special educational needs’.

SEN is a legal term used to describe “children who have a difficulty or disability which makes learning harder for them which calls for SEN provision to be made available” (Section 20: Children and Families Act 2014). In order to have a statement of SEN, the specific challenge and ensuing provision is agreed by a combination of the school, local authority, social services, doctor and/or educational psychologist. Alternatively, SEN without a statement can be agreed by a smaller group perhaps including the school and parents.

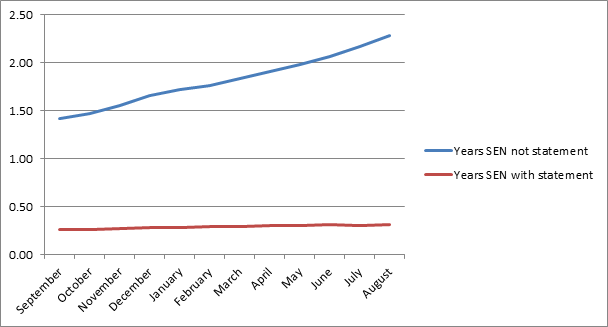

SEN labelling without statement is over 60 per cent more common for the youngest pupils than for the oldest in any year. The same happens to a lesser extent with labelling as SEN with statement, and as not having English as a first language.

SEN reporting by age-in-year, England, 2015 KS4 cohort

There is no reason to believe that genuine SEN are distributed across the population like this. It is far more likely that children with lower results at school tend to be considered for SEN labelling, which means their precise age-in-year is not being taken into account sufficiently. The distortion by age is worse when schools make the decision to label as SEN (without statement), and better when a doctor or educational psychologist is involved.

Younger children in any cohort will tend to struggle more on average, and so become visible as apparent under-achievers.

Changing the cut-off date for entry to school or allowing parents to delay starting school for their child would not solve all the problems with the system. These unfair artefacts of the school system should be amended by the age standardisation of all results, which would then form the official record for educational decisions by schools, universities, employers, individuals and family.

Stephen Gorard is professor of public policy at Durham University.

This study is based on two ongoing ESRC-funded studies and was originally presented at BERA 2017.

Co-author Nadia Siddiqui is Assistant Professor at Durham University

Unfortunately what may start out as SEN misdiagnosis can often materialise into actual problems in summer born children. See: Investigation of SEN misdiagnosis should include DfE’s role in ‘Correct but Avoidable’ diagnosis of Summer Born children

There is also a significant cost involved with avoidable SEN.

See: Money Talks: Could the publication of SEN costs FINALLY mean Fairness for Summer Born Admissions?

I agree with Stephen Gorard that allowing summer born children to begin school at compulsory school age* will not solve “all the problems” related to SEN or indeed the education system as a whole, but it is far preferable than “age standardisation of all results”.

The latter is not what parents want, and does not consider the fact that by the time some summer born children sit their exams, they are genuinely less proficient in the subjects they are being tested in than they would have been if they were allowed to begin school at age 5 instead of age 4; and adjusting their marks won’t change that fact.

The Summer Born Campaign is adamant that simply adjusting children’s scores in order to ‘pass’ them through to the next stage of their education/life is not the right answer to this problem; it doesn’t help colleges, universities or employers, and it certainly doesn’t help the child who may have had a negative experience of education for years.

Canada allows flexibility in terms of school starting age for the youngest in year, and parts of Florida also utilise grade retention for children who are not ready to move on to the next level of their primary education. A combination of these two things would help ensure all children have better results in the short and long term rather than simply adjusting their scores when they don’t.

Finally, age adjustments are used for entry exams to many grammar schools, yet there remains a disproportionately lower number of summer born children who are successful.

Could you please provide the link to the BERA presentation and the ESRC studies, as I cannot see this topic referenced at all on the BERA conference 2017 site.