Steve Lancashire is the first person I’ve met who’s wanted to be a headteacher from his school days. As chief executive of one of the largest academy chains, REAch2, and interim chief of its offspring chain, REAch4, you might think this is because he’s a power-hungry megalomaniac. Actually, it’s all because of his chemistry teacher.

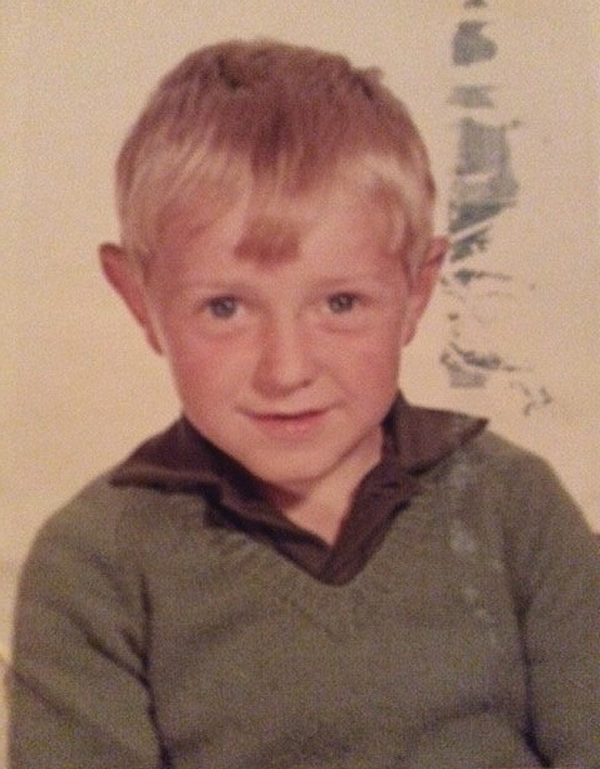

Raised in Renishaw, a village just outside of Sheffield, Lancashire had a wonderful time at primary school. It was a small village school with a few difficult hours of maths and literacy teaching in the morning, and wonderful afternoons of creative endeavours.

But his secondary school didn’t care much for what he loved. In maths, while other pupils talked of long division, he didn’t know what it was. He struggled to make sense of the numbers. And then, the chemistry teacher.

“I was scarred by that one poor teacher who makes a comment to you that he probably thinks nothing about, but which has a profound impact.

“I remember saying to him, ‘I don’t understand’, and he said, ‘In your case that’s a probability, not a possibility’. It was a chemistry lesson. I remember the actual lesson . . . to this day. It made me feel so bad.”

The comment knocked Lancashire’s confidence. It took time, and his parents’ continued belief, before he felt like an academic achiever who could go on and do well.

His father was a coal miner, his mother a dinner lady. Later, his self-educated father became manager of the pit. He was fearsome about taking control of your own learning and was determined Steve would not become a miner.

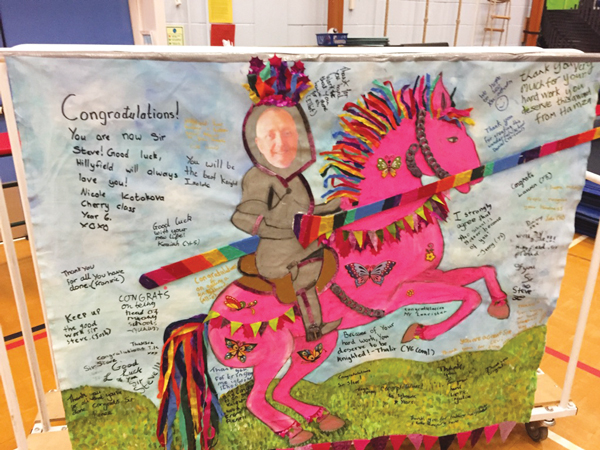

Lancashire pauses for a moment: “I’m sad he didn’t see the recent announcement, because that would have thrilled him,” he says. In the New Year’s Honours, Lancashire received a knighthood and will officially become Sir Steve once the ceremony has taken place.

“My mum’s reaction was, ‘Well it does happen to people like us’, which I think is just great. Just great.”

It’s a world away from the oft-painted (but wrong) picture of academy chain chief executives as money-grabbing business bodies. The primary school room we are sitting in also belies the idea of an impersonal “chain” – plastered as it is in posters, reminders, and pupils’ work.

“I thought plain walls were very vogue for primaries that claim to be ‘rigorous’,” I tease.

“Nonsense,” Lancashire says, and wrinkles his nose.

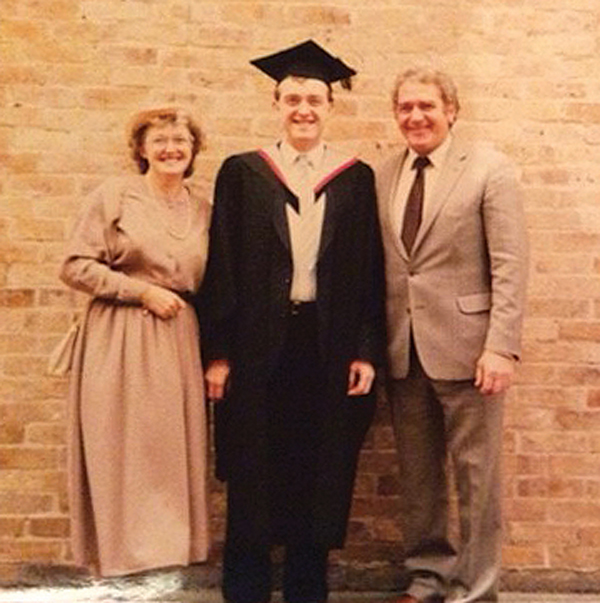

Perhaps this is because he, unlike many academy chain leaders, trained as a primary teacher. He chose his first degree, English at Lancaster University, in case he wanted to be a secondary teacher but by the time he left he decided on primary.

Studying at Liverpool’s Edge Hill University (then Polytechnic) his first teaching placements were in Skelmersdale: “And that was an education in itself!”

As difficult as the placements were, it made him realise that he wanted to work in challenging urban settings, which he has done for most of his career.

“We call Reach2 and Reach4 a family, and it is”

His first teaching job was in a Catholic school in Barking, Essex. “That was a very unexpected start, because I’m not a Catholic and I wasn’t allowed to teach RE. I taught PE when they taught religion to the children in my class.”

From “day one” he wanted to be a head and was frustrated by the pervasive view that headships didn’t happen until people were in their 40s.

“I did a lot of time thinking about how to challenge that, because I was ready to be a head . . . I just had to find a governing body prepared to appoint me. I found that governing body [when he was 30] and it was a great place to start.”

It was in Canonbury, north London and on the school’s first inspection it received a good overall, with an outstanding for leadership. But Lancashire wanted more.

For his second headship he moved to another school in Islington, north London, which had been in special measures for a long time.

“There were kids getting hit with snooker balls when they were walking down the corridors. On one occasion when I was walking around the school a chair went past me. I mean, extreme behaviour. The local authority had been struggling to find a head to take this school on, but the moment I walked in I knew I had to do it.”

Again, in contrast to the popular media image, he didn’t send children home for minor uniform infractions or make theatrical exclusions: “Absolutely not, no. No, no. I hope I’m more sophisticated than that. I hope!”

Instead, he makes behaviour management sound like common sense: “You make your expectations clear, you put in systems and procedures to support good behaviour and actually to challenge behaviour.”

Not a fan of pussy-footing, he believes that where teacher or pupil behaviour is below expectation it must be challenged.

“I’m not the kind of leader who would ever send you an email about something if I need to have this kind of conversation with you, good or bad.”

His compelling vision for schools comes across as he talks. Before headship he spent a lot of time thinking about what would make a school a good place to learn and work. It’s clearly in the forefront of his decision-making at all times.

He has also constantly looked to mentors to help stretch his thinking – naming Professor John West-Burnham as a recent inspiration: “He was one of those people who taught me to lead the way that you want to lead. Forget about leadership styles, yours will emerge, and you will know what kind of leader you want to be.”

There’s almost something tribal about the way he talks of his staff, and of the schools that now come under the REAch2 umbrella. He gurns at the phrase.

“It’s a family. We call REAch2 and REAch4 a family, and it is. I’ve got two sisters, and you couldn’t get three more different children in one family, but when things go well – like when you get a knighthood! – you get together and celebrate.

“Families fall out sometimes. But they’re there for each other. Good times, and bad times. And you . . . well, the principle I have always operated is that you must have the other person’s best interests at heart – and sometimes that means a great conversation, sometimes it means a difficult conversation, but it is always with good intent. As long as it’s got good intent, you can’t go too far wrong.”

It is this need to do good through education leadership that spurred him on to set up the second academy chain. It is the first time a chain has created a sister spin-off, and it’s an exciting development for areas such as South Yorkshire – where Reach4 will be based – as they have long struggled to get established southern chains to move north.

“I have this phrase when people ask, ‘why are you doing more?’ and my answer is: because we should.”

Asked to expand into the north, Lancashire worried that REAch2 already had so many schools that capacity was nearing its limits. But, he hypothesised, why not set up a new set of trustees and leaders using the DNA of the old trust – that is, himself and a few of the trustees?

“It’s very much about taking what we have learned and let’s start to really develop this system. This idea of a replicable model of what a trust looks like is a good one.”

He is also delighted to be back in South Yorkshire. “There have been one or two little digs about what does a London-based boy know about coming to Sheffield?

“Ah, well, actually, I know quite a lot.”

Somewhere in Yorkshire a chemistry teacher, possibly looking for a future job at a REAch4 academy, may also regret the lack of faith he once showed in him too.

IT’S A PERSONAL THING

What’s your favourite book?

For me, it’s the battle of the great women writers, so it’s either Pride and Prejudice, or Jane Eyre, or North and South.

But if the house was burning down . . .

(interrupts quickly) Pride and Prejudice!

What was your favourite childhood toy?

Definitely my Chopper bike. If you were young, you only had a Chipper. When you graduated to a Chopper it was like a rite of passage.

Where is a place you would love to go on holiday?

I’ve been to it. I’m a big fan of Australia and when I retire, disgracefully, I am going to be a beach bum in a place called Byron Bay. If I’d got long hair I’d be a hippie, but I haven’t, so I’m not going to be!

What’s your morning routine?

Up between 5am-6am. I have to have a coffee, then it’s into work.

What do you listen to in your car?

I should be telling you that it’s some fantastic symphony or something, but it’s usually Kylie.

Dream dinner party guests?

Jane Austen, Christopher Hitchens, Debbie Harry and Professor Adrian Furnham – he’s a psychologist, and I’d like him to be there to analyse my three icons and explain to me what’s going on.

Your thoughts