As the EU referendum debate continues to rage on, a new report published today hopes to shed some light on the impact of immigration from European countries on England’s schools.

Concerns over the impact on schools of a Brexit vote has taken a number of forms in the last few months – from loss of access to loans to build new schools from the European Investment bank, to the risk of losing native French, German and Spanish teachers in classrooms, which could further exacerbate anticipated problems with the new “migrant salary thresholds” on schools.

Immigration is said to be one of the foremost issues of those planning to vote to leave the EU on June 23.

SchoolDash, an education data company, has attempted to inform the debate by establishing what official government figures tell us about schools and immigration in a report published today.

The Department for Education figures do not include nationality, only ethnicity – such as “white” or “Asian”. SchoolDash was therefore unable to specifically find EU immigrants and has instead used the category “non-British, non-Irish white” (NBW) to categorise children who are most likely to be from EU countries.

Schools Week has rounded up the key points from the analysis:

The overall proportion of EU immigrant pupils is low

Nationally, 4.9 per cent of children at primary schools are NBW, and at secondary schools the proportion is 4.2 per cent.

And the increase in NBW pupils, overall, since 2011 is just 1.2 per cent.

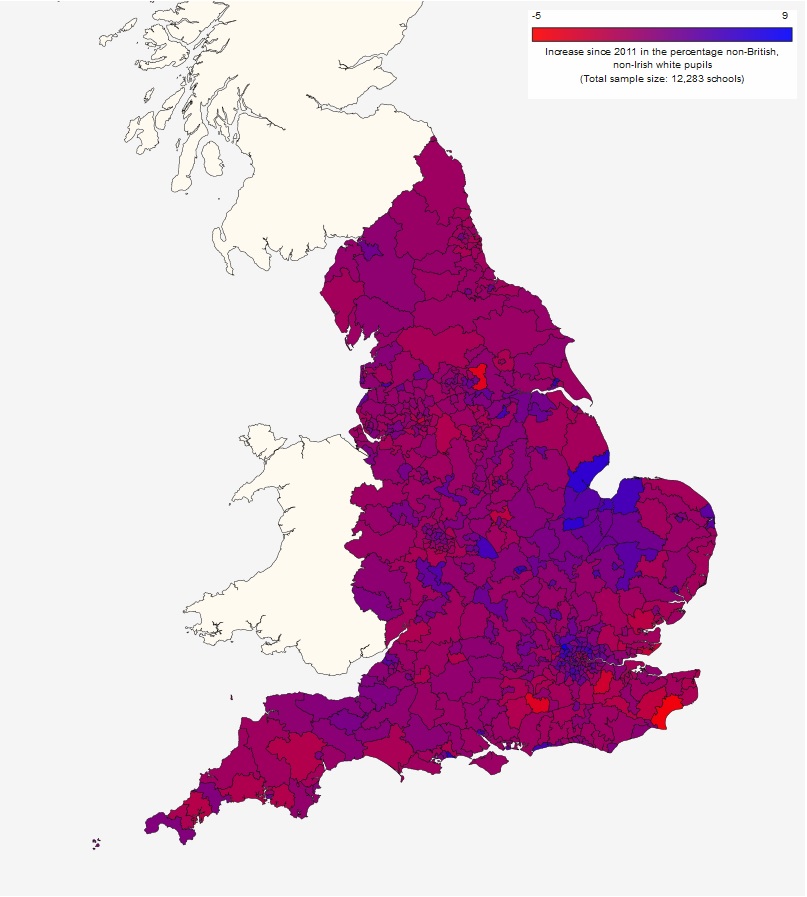

But, unsurprisingly, some parts of the country have seen larger increases (and decreases) than others during that period – as shown in the below map.

London, Boston and Peterborough, for example, have seen between a 6 to 8 per cent increase of NBW pupils, some of the largest in the country.

Conversely, in Folkestone and Hythe, there has been a decrease of 3 per cent.

Not all schools are impacted equally

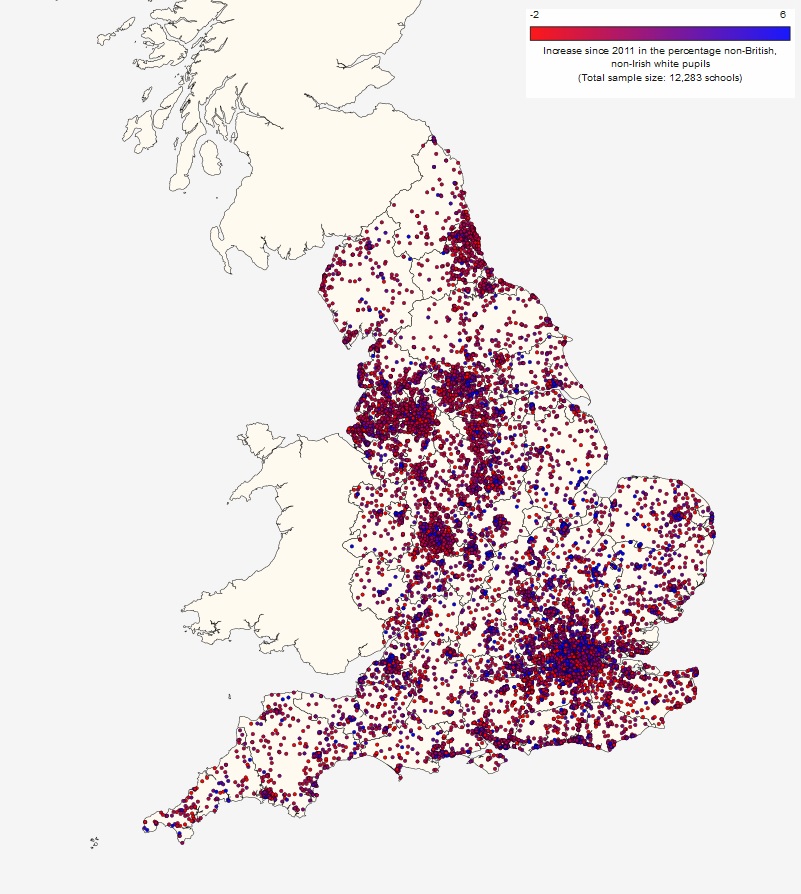

Common sense tells us that just because an area has seen an increase of children from the EU (or even elsewhere) it does not mean ALL schools are affected.

The map below shows one school may have had an increase of NBW pupils by up to 6 per cent (blue dots), but the school in the next town might have actually had a decrease by 2 per cent (red dots).

The impact, then, is generally “hyperlocal”.

Attainment – a mixed, but positive picture

SchoolDash looked at how the performance of primary schools is impacted by having greater or smaller proportions of NBW pupils.

It analysed the difference in attainment in last year’s key stage 2 SATs using four metrics: at national level; schools with high proportions of NBW pupils; schools with low proportions of NBW pupils; and schools with low NBW proportions but with similar characteristics (socio-economic etc) to high proportion NBW schools.

Here’s what they found…

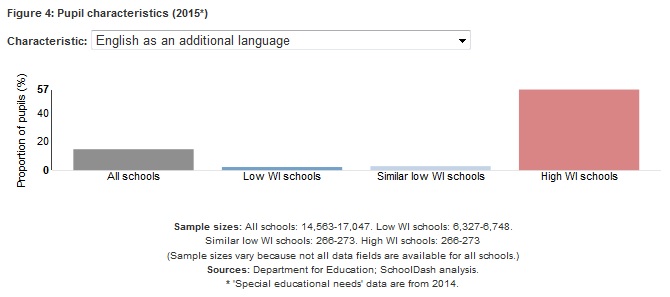

First, the make up of the schools analysed

Schools with more NBW pupils have much higher numbers of children classed as having English as an additional language (EAL) – 56.6 per cent, compared with a national average of 14.7 per cent, and just 2.2 per cent in low NBW schools.

High NBW schools also have higher proportions of children in receipt of free school meals (FSM) – about one in five, compared with one in ten in low NBW schools.

What does this mean for attainment?

On average nationally, 81.4 per cent of children achieved a level 4 in reading, writing and maths (the national benchmark). Schools with higher numbers of NBW pupils, and therefore higher numbers of pupils with EAL, do less well in meeting this target than schools with low numbers of NBW pupils (79.3 per cent compared with 82.4 per cent).

But, schools with high proportions of NBW pupils do better than those schools most similar to them, but with low proportions of NBW pupils (79.3 per cent compared with 77.1 per cent).

Put simply: pupils at schools with fewer NBW pupils generally do better. But schools with few NBW pupils but with a similar make-up of pupils (i.e. FSM/non-FSM) do worse than schools with lots of NBW kids.

What about immigrant children on free school meals?

Disadvantaged pupils (those on free school meals) in high NBW schools do better than their peers across the spectrum of schools – 73.3 per cent achieving level 4 in RWM, against 67.9 per cent in similar low NBW schools.

This is higher than the national average (71.4 per cent) and at low NBW schools (70.4 per cent).

Why?

The author suggests the impact of EAL pupils is what factors into this, and that such children come from families who place more importance on education.

This is backed up by research from Professor Louise Ryan and colleagues at the Social Policy Research Centre (Middlesex University, London).

They said: “Migrants to Britain often originate from countries where there is a high regard for education and great respect for teachers. These migrants place a high value on education and encourage their children to work hard in school and listen to their teachers.”

But London has quite an impact on the above results

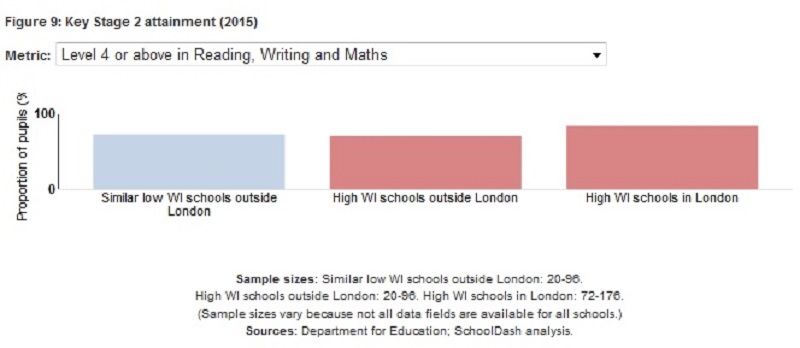

London is, as always, the outlier in these statistics, as shown by the following graphs and figures.

The graph below shows how schools with high NBW proportions in London compare with those outside. For KS2 SATs, 84 per cent of pupils at high NBW schools in London achieved a level 4 in RWM, while just 70.8 per cent of pupils outside London did.

SchoolDash calls it “Laudable London” and says “if you believe (as some do) that London’s educational strength comes in part from its ethnic and linguistic diversity then you could reasonably conclude that having a lot of white immigrant children at a school is likely to help rather than hinder its academic progress”.

Schools Week has previously reported about the impact on EAL pupils and London in national figures for attainment. While overall EAL figures will include pupils from a large number of countries outside the EU, it does show how the difference in provision in schools could be what has more of a bearing on results.

Dr Antonina Tereshchenko, research associate at King’s College London, found, by analysing the National Pupil Database for the GCSE results of pupils whose first language is recorded as either Bulgarian, Czech, Estonian, Hungarian, Latvian, Lithuanian, Polish, Romanian, Slovak, Slovenian, or Russian that there has been a marked improvement in results.

She said: “Over the last five years, pupils speaking the above Eastern European languages as their mother tongue have seen a steady improvement of their KS4 results. For example, between 2009 and 2013 the proportion of these pupils leaving secondary education with five GCSEs at grades A*-C increased by 22.2 per cent, compared with an average for the national cohort of 11.8 per cent.”

Her research also found the gap between disadvantaged Eastern European pupils achieving five A*-C GCSEs, including English and maths, and their non-FSM pupils was just 3.2 percentage points in 2012-13, compared with a national average of 26.9 percentage points.

What the author says

Dr Timo Hannay, SchoolDash founder and the son of a Polish immigrant, said it was “not surprising” he was in favour of free movement, but said the findings were analysed and presented “objectively”.

Dr Timo Hannay, SchoolDash founder and the son of a Polish immigrant, said it was “not surprising” he was in favour of free movement, but said the findings were analysed and presented “objectively”.

Hannay added: “The effects of EU immigration in terms of both numbers and their effects on academic attainment therefore appear very local, with most areas largely unaffected, a few areas heavily affected and London positively thriving, at least in terms of academic outcomes.”

In the late 1990s my headship school admitted about a dozen Kosovar children across all years of the school. The families had been granted asylum and given temporary accommodation in Ulverston as part of a national scheme reacting to the Balkan conflict. The numbers in each year group were small, so no extra classes had to be created. The Cumbria LA created an Officer post in the Barrow Education Office and we liaised with her very effectively. She may have provided some out of school support for the families and the children, but we provided none, other than through the extensive support systems we had for all our pupils. All the Kosovar pupils and their families were Muslims, not that anyone would have noticed. Neither the parents nor their children wore any kind of distinctive clothing. I cannot remember if the mum’s wore head-scarves even. All of the pupils had English as a second language. By the time they were admitted to our school they had been in England many months and their English was already good. Some extra support was given but this did not make much in the way of extra demands over the huge amount of support we provided for our native pupils.

The parents were hugely supportive of their children. They were also organised and negotiated the school places with the LA as a group, not individually. They wanted to know a lot about our school before they agreed to admit their children. They visited other schools in the town that got far better GCSE results than us.

So how did it go? Brilliantly. All the children settled very well, made good friends and made excellent academic progress – far better in fact than the average for our inner urban working class intake. One Kosovar family moved away to Manchester, but after a few weeks returned, giving the ‘poor school’ and bullying as the reason. Some of the children were still in our school when I retired in 2003. Others had taken GCSEs, got good results and progressed to the Sixth Form College and later to University.

I did have a personal role in this because as the conflict in Kosovo settled they were put under pressure by the immigration authorities to return to Kosovo. Most wanted to stay and I successfully supported them in immigration tribunals held in Leeds. Why did I do this? First, because as a teacher I always felt a duty to be on the side of children and their families. Second, because these children and their parents were a huge asset to our school, both academically and socially. Why would our school want to lose them? They were fully integrated and involved in our School Council. Third, because the families were clearly an asset to Barrow.

I realise it is not possible to generalise from our very positive experience, but I do think that all this talk of immigrant families putting a strain on services like schools is much exaggerated. Our Kosovar families were well educated and the parents held good jobs back home. However they and their children had certainly seen some terrible things in the conflict with the Serbs. But, all of this this is generally true now of the majority of asylum seekers from the conflict in Syria.

Our experience was overwhelmingly positive.

It would be a tragedy to turn any local logistical problem into a crisis, or worse, create community tensions where none need arise, as a result of the exploitation of fears through the EU referendum.

At the end of WWII Leicester received huge numbers of Polish refugee families and some from other Eastern European countries. By the 1970s these families were well established and integrated into the life of the city. From 1973 to 1975 I taught physics at Wyggeston Boys School, one the most prestigious grammar schools in the country (the Attenborough brothers were former pupils). Polish and Balkan surnames were over-represented in the school compared to the local population, and were always especially numerous amongst the school’s highest achievers.

A few weeks ago the CEntreForum annual report caused a deal of controversy. I take issue with the true nature of the ‘attainment gaps’ that they discuss, as explained in this article.

https://rogertitcombelearningmatters.wordpress.com/2015/01/07/closing-the-gap/

However, the raw data from the CentreForum report shows that ‘white British’ pupils are amongst the poorest school performers on a wide variety of measures compared with a large range of children from other ethnic/national backgrounds. This suggests that the positive experience of our school and our Kosovar children may be closer to the truth than the stories of schools and ‘native’ children disadvantaged by the influx of children with English as a second language. I can’t find the sources, but I don’t believe that hard attainment evidence shows any disadvantage at all. A lot of this is simply mistaken ‘common sense – driven’ prejudice: the idea that such children will ‘take up more of the teacher’s time to the detriment of my child’.

It could be that the influx of English as a second language pupils into state schools is actually on balance a bonus, with positive outcomes well worth the small amounts of extra provision needed.

My book, ‘Learning Matters’ is as much about dispelling ‘common sense’ myths about education as anything else.