Sam Gyimah has just moved into David Laws’ office in the Department for Education’s Sanctuary buildings – a fact he points out with nervous laughter.

But the junior minister laughs less when he talks about working with his Liberal Democrat counterparts in the coalition.

“We achieved certain things together, but what was deeply frustrating sometimes is that we had coalition partners who always wanted to claim that they were the good guys and they cared about social justice . . . and that everything that was not about social justice was us, when actually we were as one on social justice.”

Gyimah is warm, but seems a tad anxious. His family life is clearly very precious, and he is keen to keep those closest to him out of the spotlight – “they are not politicians”.

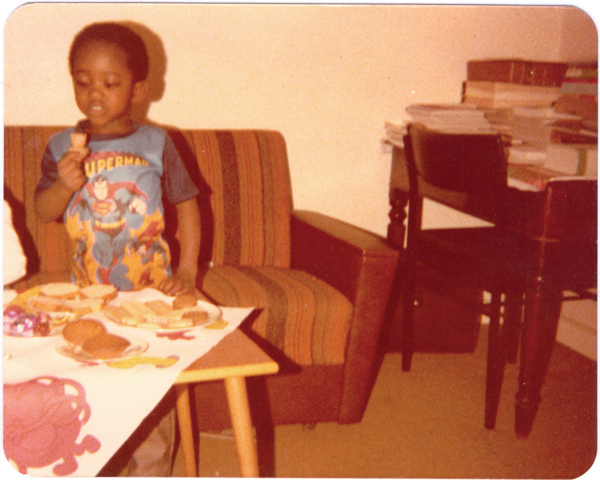

He nevertheless opens up about his childhood, and a life full of huge transitions. The first taking place when he moved to Ghana’s bustling capital Accra when he was six. Quite a different place to the town where he was born and had always lived in: Beaconsfield in Buckinghamshire.

The move was spurred by his parents’ separation. His mother relocated him, his younger brother and sister (a baby at the time) to Ghana, where she worked as a nurse at the university hospital.

“She did a good job of shielding us from what was otherwise quite a difficult transition for the family and difficult for her – finding herself in her 30s with responsibility for three children.

“She was very good at focusing us on our education, because I ended up starting school later [at six and a half] than I would have otherwise.”

The subject of his relationship with his father appears a sensitive subject. Gyimah says for many “complicated reasons” he doesn’t want to go into his involvement with him after the relocation.

Did he notice a lack of a male role model in his life?

“You don’t think of who your role models are as a kid, but it was hard because I am the eldest.

“I could see the strain my mother was under and the effort she was going through to be the breadwinner, primary carer, chief motivator and driver all at the same time, and to try to give us the impression that life could continue as normal.

“She was brilliant – she gave us a sense that a thing might happen but you can still do well in life. She was also really keen to push us at school and keen that we couldn’t use that [the separation] as a reason not to do our homework, for example. And she was, by and large, successful.”

His mother even pawned her wedding gifts to make ends meet.

Starting school in 1981, each class contained about 50 children and he describes a sense of knowing that education was the “passport” into life – although Ghana “was not much fun” at the time and it was “tough”.

“Rawlings had just got into power for the second time and there was political unrest. I remember we had power cuts because there had been a drought. The electricity in Ghana is driven by the dam and if there is no water in the dam, there is no electricity.”

Despite this, he says his childhood was filled with happy memories.

A lack of secondary schools, bar for a few state boarding schools, meant a secondary education was not an option for everyone. He doesn’t think about what “could have been”, but he was very conscious of needing a secondary education.

Gyimah got a place at Achimota School, an hour and a half from home, which had piano keys as its crest. Its motto read: “You get perfect harmony when you play the black and white keys.”

“For a country that was trying to escape its colonial past, saying to people they could be successful – and working together was the way to do it – was incredibly powerful. I’ve worked in many environments that are diverse, and when you have got diversity the sum is greater than the individual parts.”

He hated the school at first, until he “made friends and realised, like most teenagers, you enjoyed being with friends rather than being at home”.

It was then that his father “suddenly decided [he] was doing well at school” and given that Gyimah already had citizenship, he returned to England to Hertfordshire – to do his A-levels at Freman College, a state school.

He was now one of only three non-white students and facing what he describes as a more “flexible” approach to learning. His school shorts had to be an exact length, for example, in Ghana; his uniform there was merely a suit-based “dress code”.

His history teacher, Mr Greenhalgh, inspired him and put effort into encouraging his Oxford application.

“I think I am lucky to always have had people who are incredibly supportive . . . that’s what makes the difference.”

Gyimah got a place at Somerville College in 1995 and studied politics, philosophy and economics – something his mother took a while to forgive, expecting him to become a lawyer, a doctor or an engineer, not study “this philosophy stuff”.

His first election “itch” came when putting himself forward for president of the Oxford Union. He won, becoming the first black president for a half a century. “It was overwhelming . . . but overwhelming is never a reason not to try.”

He struggled to support himself at university and could have been kicked out had he not negotiated a loan with the college bursar on the basis that he would pay it back after he finished university.

A job as an investment banker at Goldman Sachs – “someone has to do it,” he shrugs – secured this repayment. But he regrets now that he didn’t continue with his education and become a barrister.

He liked the sound of David Cameron when he was made leader of the party and decided to make a foray into local politics. He unsuccessfully ran for a council seat in Kilburn and in 2010 was elected as MP for East Surrey.

He laughs when asked about how he and his wife met. They met at university but it wasn’t until 17 years later they got together. “She claims it took me 17 years to pluck up the confidence but I say she wasn’t ready for me.”

They married in 2012 (he almost forgets), and their son is now 14 months old. “He is walking, and he thinks he can run away from you!”

Like many others, the couple has to balance childcare with full-time jobs.

Having a son has “sharply focused” his views on childcare and education. “You are making policy decisions. Then you go home and you can actually think ‘if my little one is in this position would I be thinking about it in the same way as I would in the office’?

“Thinking about [childcare responsibilities] means that your feel for this subject matter is not just an intellectual one. It’s one that you are living, but you ultimately have to make policy decisions based on the evidence.”

IT’S A PERSONAL THING

What was your favourite childhood toy?

It’s not an abacus or Rubik’s cube! Running around and playing outside is my favourite childhood memory. We invented all sorts of adventures and occasionally I hurt myself, but it was immense fun.

Where would you like to go on your next holiday?

Looking forward to my next trip to San Francisco to see my wife’s family.

What do you eat for breakfast?

I’m a creature of habit. It’s cereal, a cup of tea and an orange juice most mornings.

What is your favourite book?

Birdsong by Sebastian Faulks. I tend to like novels set in a historical context.

What did you want to be when you grew up?

Depends on what age you would have asked me! I think a lawyer, most of the time. That was the ambition that persisted the longest.

If you could live in one historical era, when would it be?

I loved history. The French revolution and nationalism in 19th-century Europe I just loved, partly because of the issues of identity that Europe was going through. If you are born in one country and spent a little bit of time growing up in another, you are very conscious of what makes identity and how it is defined. I always wondered why Louis XVI didn’t concede things in the revolution . . . why did he allow things to run for so long? He should have called the Estates-General the moment people asked for it. That’s when I began to think about politics; how it’s conducted and shaped.

Your thoughts