The poorest pupils have made more progress than their better-off peers at just three per cent of secondary schools, new analysis shows.

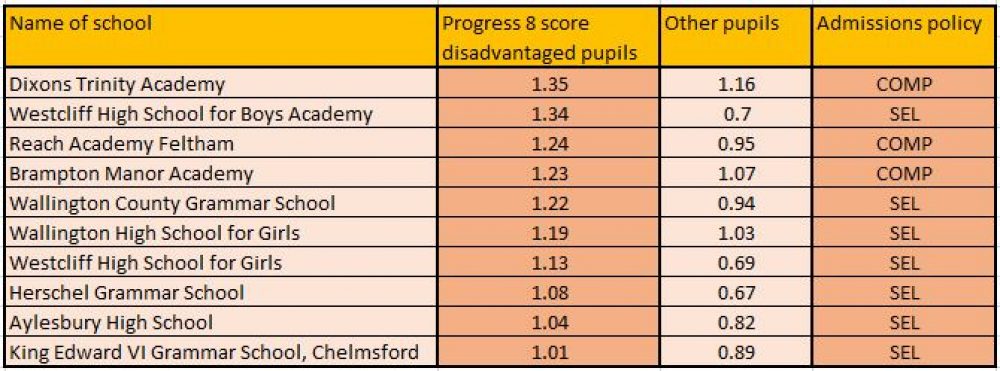

About 100 schools posted a positive Progress 8 score for their pupils on free school meals, or who were on free school meals at some point in the last six year, which beat the positive score of more affluent pupils – and nearly a third are selective.

Researchers at Impetus-PEF, an education consultancy, said “very few schools” are ensuring these pupils, whom the government classes as ‘disadvantaged’, make enough progress to catch up with their peers.

Andy Ratcliffe, its chief executive, said the school system should want to “bottle up” the work of these schools and emulate it, pointing to “brilliant leadership” and “constant focus on success”.

But experts in value-added measures insist that Progress 8 is fundamentally flawed, and said the data could favour grammars.

Just 102 schools out of the 3,526 secondary schools for which data was available posted a Progress 8 score that was better for disadvantaged pupils than non-disadvantaged meal pupils, and in which both groups also scored above 0.

The pupils with top scores were those with rich relationships with staff

The figure, from government performance data released last week, is a slight drop on last year, when 107 schools improved the poorest pupils the most. Overall this year 687 schools posted positive progress scores for both disadvantaged and non-disadvantaged pupils, but the majority, bar the magic 102, still recorded better progress scores for wealthier pupils.

Headteachers have pointed to a culture of “high expectations” for achieving top scores.

Dixons Trinity Academy in Bradford came top for the progress of its poorest pupils, with a score of 1.35 for disadvantaged pupils compared with 1.16 for the rest.

Luke Sparkes, the executive principal, said the result was due to the “whole school being designed around our most vulnerable student”, with strategies such as morning and afternoon feedback sessions every day, and double-staffing core subjects so one teacher could always give dedicated support.

An “achievement-oriented culture” and a “razor-sharp focus on data” is also vital, he said.

His words were echoed by Ed Vainker, principal at Reach Academy Feltham in west London, which came third with a score of 1.24 for disadvantaged pupils compared with 0.95 for other pupils.

Both schools opened in 2012 and had their first GCSE cohort last year.

“Starting from scratch” allowed the school to focus on “powerful relationships” between teachers, pupils and their families. Home visits before the start of term and using teachers’ first names, as well as a team of counsellors available daily for mental health issues, also helped.

The pupils with top scores were “those with rich relationships with staff”, he said.

Progress 8 is a flawed measure because it relies on error-prone assessments of pupil attainment

A spokesperson for Harris Academy Chafford Hundred in east London, which posted a 0.99 score for disadvantaged pupils and 0.8 for non-disadvantaged school meal pupils, said the higher score was down to the school’s intervention strategies “tending to benefit” the poorest pupils most.

But the data also showed many grammar schools made better progress with the poorest pupils than their more affluent peers. Schools Week analysis revealed 27 per cent of the 102 schools are selective, and 29 per cent are single-sex.

Professor Stephen Gorard of Durham University, who has studied value-added measures, said it would be better to use a measure which showed the proportion of years a pupil has been eligible for free school meals.

He said “this measure of disadvantage recognises the chronic nature of poverty in some areas and some types of school.”

Meanwhile Progress 8 is a “flawed” measure because it relies on “error-prone” assessments of pupil attainment, and so tends to produce “unstable” results over time, he added. This is backed by Schools Week analysis which shows 15 schools cropped up in last year’s data set as this year’s. All other schools were new.

The data should be run for at least five years before the schools which work best with pupils on free school meals can be determined, said Gorard.

Actually, I was proposing the use of the proportion of years any pupil is known to have been eligible for free school meals. This measure of disadvantage recognises the chronic nature of poverty in some areas and some types of school. It leads to stronger predictions of KS4 attainment than either current FSM or FSMEver.

Quite right to look at what these schools are doing to enable disadvantaged pupils to succeed but a crucial element is missing from the table – what is the proportion of disadvantaged pupils in each school?

You’re right. Selective schools for example have a much lower percentage of FSM pupils than comps.

Studies have shown that flipped classrooms improve school standards in poor areas. Can anyone name any other technology (or method) that gives poor children such a big boost for a relatively low cost?

And which studies would they be?

Well done Dixon’s- a brilliant achievement. But I do think that this analysis really should have the number (& proportion) of disadvantaged pupils published too. For example, the top 5 selective schools recorded here have a very small proportion of disadvantaged children (c.6% to 17%). This is not an attack on the achievements that these schools have made for these kids. However, if we put small numbers of disadvantaged pupils into these schools the kids will do better. If selective schools want to make a greater difference, then we need more disadvantaged kids to be offered this provision (& stay & succeed).

Interesting that the two free schools started from scratch allowing them to build up the school gradually. This is one factor that can’t be replicated in existing schools.

That said, congratulations to the comps in the top list. Selective schools don’t counted – there’s no gap to close.

Given the most under-performing group of students nationally are white, british, pupil premium boys, any chance schools could be identified where such students outperform all others? Would make the article much more interesting and useful. Surely SOME schools must manage it? Surely…

I wonder why no-one has had a look at the difference between LA-run community schools and academies/free schools in the context of this story…

The result of my quick fag-packet calculations (which I’m sure aren’t 100% correct, but I think are probably pretty much on the money): the percentages of schools which have higher FSM than non-FSM Progress 8 scores are:

Free Schools – 6%

Academies – 3.2%

Community Schools – 0.8%

The only reason I had a look is because I was pretty confident that if the figures had been the other way round it would have featured heavily in the article. No comment on what this means, or if it should be seen in any way as a positive thing for academies. Just thought it was interesting.

There are seven selective schools in the ‘top’ list. Thus, the best way to close the gap is to ensure there isn’t one to start with. http://www.localschoolsnetwork.org.uk/2016/11/attainment-gap-between-better-off-and-poor-pupils-disappears-when-schools-select-only-the-brightest-poor