Twelve months into the job of CEO at The Active Learning Trust (ALT), Stephen Chamberlain talks to James Carr about a year that has been more tumultuous than anyone could have expected

Stephen Chamberlain has always enjoyed a challenge. But, as we have all collectively learned, there is a stark difference between the challenges of old and the challenges of a global pandemic that seems to produce daily conundrums each more testing than the last.

Chamberlain took the helm as chief executive of The Active Learning Trust (ALT) in November last year. The first year in any new job can be daunting at the best of times, but within 12 months of taking the role he has navigated nationwide school closures, school reopenings, government flip-flopping on free school meals, the move to online learning, shortages of laptops for vulnerable pupils, national lockdowns, local lockdowns and one of the most controversial exam series in history.

This also came on top of the, thankfully, incredibly rare circumstances of taking on a trust in the wake of tragedy: its popular leader, Gary Peile, who had served as CEO since 2015, passed away in February 2019 aged 63 following a long battle with cancer.

CEO seems to be the role where I can have the biggest impact

It is surprising then when we chat to find Chamberlain is so upbeat, an eternal optimist determined to find solutions to the constant obstacles thrown his way. “We forget the list of challenges the sector has been having to face as there have been so many,” he explained, “we just resolve it and move on to the next issue.”

Chamberlain grew up in Tottenham, attending an inner London comprehensive during the 1970s in what he calls “quite a challenging time”.

It was during this period he learned a valuable lesson that continues to shape his approach to education.

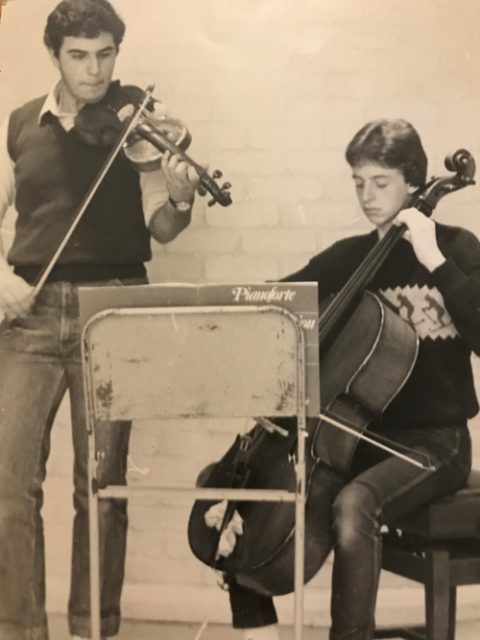

Aged eight he picked up the cello for the first time and a lifelong love affair with music began. By 11 he had joined a junior orchestra in Haringey and by 16 had earned a Grade 8 with distinction from the Royal Schools of Music. He went on to play across the UK and Europe with semi-professional orchestras, performing at outdoor evening concerts in Barcelona and in major concert halls in Prague and Budapest.

Chamberlain discovered that music and the arts have the power to be “transformational”. He explains music allowed him, the son of a builder and local office worker, to play in orchestras with people “from all walks of life” and became “quite a leveller”. He added: “Music and art has the power to transform schools and communities.

“It was music which got me through school. When education was difficult, music was the thing that made a difference. When I came into teaching I always looked for jobs where I could make a difference, either in the classroom or wider community.

“CEO seems to be the role where I can have the biggest impact on the largest number of children.”

Starting his career as, you guessed it, a music teacher in 1987, Chamberlain saw this impact in action first hand and since becoming a headteacher in 2005 he has made the arts a key feature of his leadership.

In 2009 he joined Academies Enterprise Trust as regional director of education for the east of England and became founding principal of the Clacton Coastal Academy.

Many of the academy’s pupils resided in nearby Jaywick ̶ still one of the most deprived areas in England and “at the time one of the most deprived wards in Europe”.

Chamberlain explained he was keen to “provide a strategy for all those young people who were experiencing poverty” and ensure their experience of school was “enriched” beyond the usual mainstream curriculum.

For example, engagement with extra-curricular activities after school was extremely low as pupils were unable to get home without the aid of school transport.

To make sure pupils did not miss out, Chamberlain introduced an “elective period” during the school day in which pupils could immerse themselves in arts and music.

The strategy worked and between 2011 and 2014, during which time he switched to an executive principal role, the academy progressed from ‘Satisfactory’ and ‘Requires Improvement’ to being rated ‘Good’ by Ofsted.

The schools watchdog even highlighted Chamberlain as the academy’s “key strength”, whose “leadership and vision…raised the expectations of staff and the aspirations of students”.

We stand on the shoulders of giants in many ways

A role as CEO at the Challenger Multi-Academy Trust (CMAT) followed in 2015, with Chamberlain continuing to focus on character education and broadening the curriculum outside the classroom. The trust leader spoke of his belief the sector needs to “revalue a broader curriculum across the arts” as the “more things pupils take on outside mainstream curriculum the richer their lives will be”.

Then last November, Chamberlain made the leap from the eight academies of CMAT to the 21 at ALT. At the time ALT was at something of a crossroads. Just nine months earlier Peile had passed away – the loss cast a long shadow over the trust and led to schools suffering from “gaps in the continuity of strategy”.

Kingsfield Primary School saw its Ofsted rating drop from ‘Requires Improvement’ to ‘Inadequate”, with Chamberlain stating problems at the school and its revolving door of leadership were not “at the forefront of the trust’s mind” in the wake of the tragedy.

However, work to “drive standards” soon began, with the trust working to support leaders at its most challenging schools and engage in forensic deep dives into problems.

Chamberlain describes his predecessor as “a very talented man” who always put the trust’s pupils first and admitted “they were big shoes to fill”.

“Gary had been very successful and the trust had been very successful and I’m always mindful of building on that legacy. We stand on the shoulders of giants in many ways”, he added.

But just four months after taking the role the coronavirus pandemic hit the UK – changing what it meant to be a school leader.

“There’s no training for CEOs that prepares you for this one. Normally in this kind of role you are more focused on the long-term strategy. This [the pandemic] obviously changes the work we are doing.”

Chamberlain said the sudden change of circumstance was initially testing but the “ultimate test of leadership” is how you deal with a crisis.

“I see being a CEO as more of a service role, I’m there to serve the heads and make sure they can do their job.

“I see being a CEO as more of a service role, I’m there to serve the heads and make sure they can do their job.

“If the heads feel I’ve got their backs then at this time that’s the best kind of leadership I can offer.”

The CEO is quick to shift any praise on to the teachers and pupils within the trust who he says have gone above and beyond at every turn.

Ever the optimist, he is also eager to highlight some of the positives that have been born out of the disruption, highlighting how the sector came together and collaborated outside normal structures to solve problems.

He added: “I wouldn’t wish a pandemic on anyone but the impact can be used as a positive to drive things forward at pace.

As the CEO, it is not my trust. I am just the custodian

“It has allowed us to look at our systems and processes in much more depth than we would have in normal circumstances and it has allowed us to make changes that will actually be sustainable and have an impact in the future.

“Even though this crisis is still continuing, you still have to have an eye on where the organisation is going and continue to develop.”

Prior to the pandemic a key area of focus for the trust was the retention and growth of staff through professional development.

Since the disruption began this development, much like the trust’s curriculum, has moved online, allowing easier access and engagement for busy staff who were previously forced to travel long distances to receive the training.

Chamberlain added: “There’s a sense that the heads think it is their trust ̶ theirs and the communities’ and the children’s.

“As the CEO, it is not my trust. I am just the custodian, it existed before me and it will exist after me.”

Your thoughts