Private schools are bumping up their fees while state school funding remains flat, widening the attainment gap between the state and independent sectors, academics have claimed.

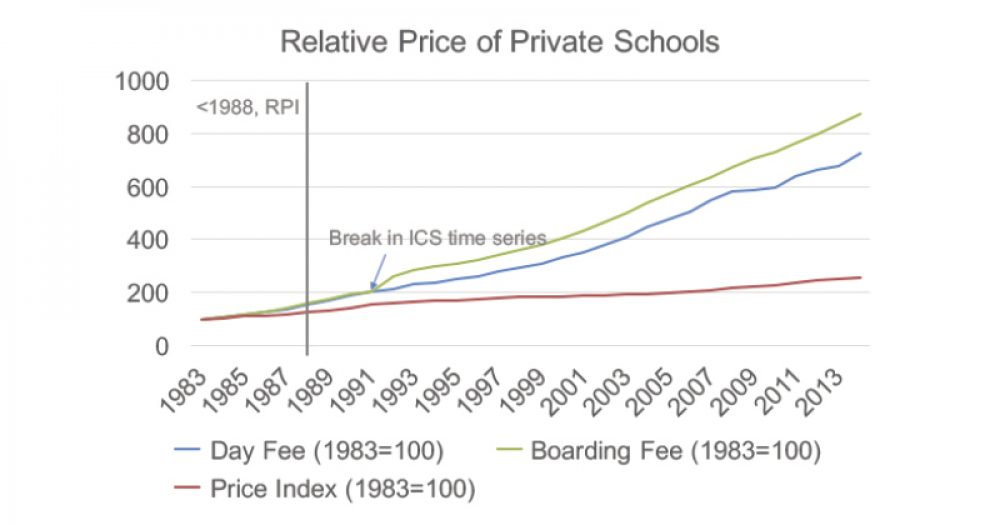

Research published this week by the UCL Institute of Education, titled The labour market benefits of private schooling, has found that fees within the private sector have increased well above the rate of inflation (see graph).

Researchers said private schools had used some of the extra cash to modernise facilities – resulting in private school pupils having three times more spent on them than their state school counterparts.

Anna Vignoles, professor of education at the University of Cambridge and a co-author of the report, said: “We’ve been looking at adults whose private schooling happened two decades ago. But what we can see is that the resourcing levels within private schools have increased exponentially since then.”

Her research found adults in their 40s who had been privately schooled on average earned 35 per cent more than those from the state sector.

“The advantage 20 years ago was big, and if resourcing is increasing we can expect that advantage to become greater too.”

Previous research by Professor Francis Green of the UCL Institute of Education, who also contributed towards the new report, found private schools were investing more in their facilities.

£12,200 is spent annually on a privately schooled pupil, compared with £4,800 on a state school pupil

According to his research, about £12,200 is spent annually on a privately schooled pupil in primary school, compared with £4,800 on a state primary school pupil.

At secondary, £6,200 is spent on each state school pupil a year, while in a private school that figure is £15,000 for a day pupil, and £30,000 for a boarder.

Green said parental demand had led private schools to modernise their facilities to keep up with the competition, pushing up fees to a level that only the very wealthy could afford.

“Parents are prepared to pay these higher and higher fees. So schools compete with each other to provide better facilities – a state-of-the-art theatre or Olympic size pools.”

Green also said the extra cash coming in to private schools allowed them to employ more teachers, meaning more time on developing pupils’ “non-cognitive skills”, such as confidence.

Vignoles said: “There is no evidence that teachers in private schools are necessarily better. But the class sizes are two-thirds of what they are in a state school. Better teacher pupil-ratios are crucial.”

A spokesperson for the Independent Schools Council, which represents more than 1,200 private schools, said citing money as the reason for higher educational outcomes was “over simplistic”.

“Fees have increased but schools are very mindful of the struggles hard-working families can face in paying them.

“That said, pupil numbers continue to increase, both those paying full fees and those receiving fee assistance, often paying nothing at all. The more pupils who pay, including those from overseas, the more bursaries can be offered. This creates demonstrable social mobility.”

‘…demonstrable social mobility’: offering a few bursaries, many of which are means-tested, to a small number of ‘poor’ pupils is not ‘demonstrable social mobility’. In any case, education’s contribution to social mobility is over-stated. It’s more to do with the supply of jobs which pay well enough for young people to live at least as well as their parents and social policies which lift people out of poverty.

If the “attainment gap” between private and state schools is not a consequence of spending 3 times as much on privately educated students, I suggest reducing the fees at private schools to the same level as that of state provision. Then the private schools could educate more of the students that they claim they want to assist.

State schools are constantly criticised for not achieving the same results as private schools. Imagine criticising a farmer for not achieving high yields when he was allowed one third the plant growth fertiliser of his neighbours. The poor farmer not only has to accept the criticism, he has to work harder to get a reasonable yield, and his seed corn is of a much more variable nature. The parents who pay for educational privilege know this full well. It would be a step forward if paying for advantage was acknowledged and the hard work of the “poor farmers” was recognised.

At a very high level of wealth the fees are irrelevant. What is interesting is why at more modest income or wealth levels iwhy so much is paid for a service that is available free of charge? Either the service is of very high quality or the free service is well below par. Or both. The debate should not be about explaining differences in performance because of finance but about how that situation arises in the first place. If those on lower incomes could use the state resources towards private fees it would revolutionise the educational market place. The legacy of decades of political interference is profound. We should either make Prvate education illegal or allow every family to use a voucher from the state towards private exucation, Either would shine a torchlight on the root cause of the problems. The status quo is not working and neither the right nor the left have the stomach to to really open up the issues.

.

Maintains the status quo will, I am afraid, maintain the status quo!

The reason middle income households pay so much is that they believe it offers a better education, better prospects, better connections, better facilities ect.

ds