Her Majesty The Queen has today set out plans to force “coasting” schools to become academies.

A new education and adoption bill was one of the first pieces of legislation announced in the Queen’s Speech this morning, and sets out the legal means by which the government will tackle schools labelled as “coasting”, a new status not yet properly defined by the government.

The bill will give regional schools commissioners (RSCs) powers to bring in “leadership support” and will “speed up the process” of turning schools into academies.

A briefing on the bill talks about removing “barriers” to conversion of inadequate schools.

But it also said schools which meet a new “coasting” definition, for example, if they show “a prolonged period of mediocre performance and insufficient pupil progress”, would be eligible for forced conversion.

The briefing added that a coasting definition would be set out “in due course according to a number of factors”.

The Queen’s Speech also included previously-announced plans to offer an extra 15 hours of free childcare a week to working parents, on top of the 15 hours currently offered universally.

Unions raise concerns

Unsurprisingly, the coasting schools initiative has not been warmly welcomed by union leaders.

Dr Mary Bousted, general secretary of the Association of Teachers and Lecturers, described what she called the “forced academisation programme” as “policy-making without evidence that it will work”.

She added: “There is no proof that academies perform better than other types of school and there is great variation in the effectiveness of different academy chains.

“If Nicky Morgan was serious about evidence she would allow academy chains to be inspected on the support and challenge these chains provide for their schools. It is remarkable that she has prevented Ofsted from inspecting chains – what does she have to hide?”

She said the announcement was a concern, as the government had still not defined what a “coasting school” is, and said it remained unclear what interventions those schools considered to be coasting would face.

Russell Hobby, general secretary of the National Association of Head Teachers, warned that the government would need

more than new powers of intervention to tackle the “clear challenges” facing education over the next five years.

He said: “The number of children is rising at the same time that recruitment of teachers is becoming harder. Unless the government develops a clear plan to fund and organise places in already over-subscribed areas, and to make teaching a more attractive profession, these problems will grow.”

Mr Hobby said free schools alone would not meet the need for places, and called for funding for better training and development.

He also said forced academisation was “not guaranteed to work”, and said the government needed a “wider range of strategies”.

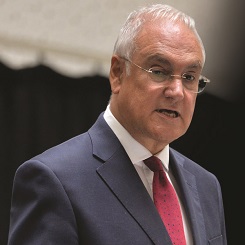

Wilshaw backs intervention plan

Ofsted chief inspector Sir Michael Wilshaw backed government plans to intervene in “coasting” schools.

The BBC has reported that Sir Michael has thrown his weight behind the government’s plans, but raised doubts about whether enough outstanding headteachers could be found to replace leaders at weaker schools.

He is also said to have expressed concerns about an apparent postcode lottery of good and bad provision, adding: “Why should a child in London, or parts of Liverpool or Newcastle have a better chance of going to a good school than a child in Suffolk or Norfolk?”

The Confederation of British Industry has also come out in favour of government plans.

Deputy director general Katja Hall said: “The government is right to take steps to ensure that our education system does not tolerate underachievement.”

‘Coasting’ will mean whatever the DfE, politicians, academy brokers, regional commissioners and Ofsted say it means. And what is ‘mediocre’ performance? Is it 50% of pupils reaching the benchmark in a school where the intake is skewed to the bottom end? Or would 85% reaching the benchmark be ‘mediocre’ if it’s a grammar school?

Ah, the definers of ‘coasting’ will say, ‘We’ll look at progress’. But progress is an unreliable measure. Children don’t progress uniformly. Learning isn’t unrelentingly vertical: there are peaks, troughs and plateaus. Children could be anywhere on this wobbly path and all at different times.

Even if it were possible to accurately measure ‘progress’, academization is not, as the Government claims, the best way of raising standards in underperforming schools. The Education Select Committee told politicians to stop exaggerating academy success. And the National Audit Office found informal interventions such as local support were more effective than formal interventions such as academy conversion (and cheaper, of course).

Yet Morgan, like Gove before her, ignores the evidence and presses on with an expensive and ineffectual policy.