The gap in achievement between 15-year-old pupils in England in key subjects is one of the largest and most unequal among developed countries, a release of international test data showed.

But a government report on the results of the tests taken last year by over 5,000 pupils across the country, plays down the importance of grammar schools in resolving the situation – despite ministers choosing to highlight the policy this morning.

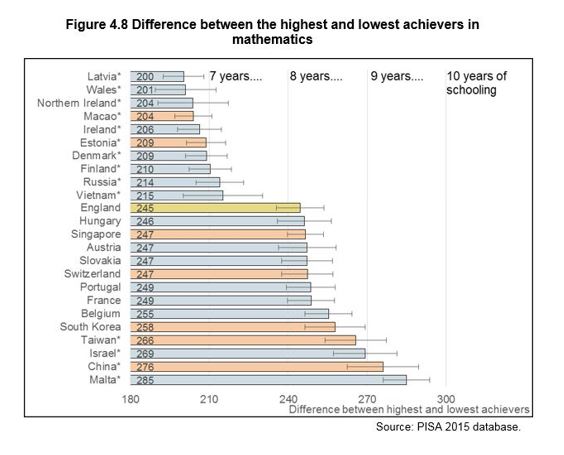

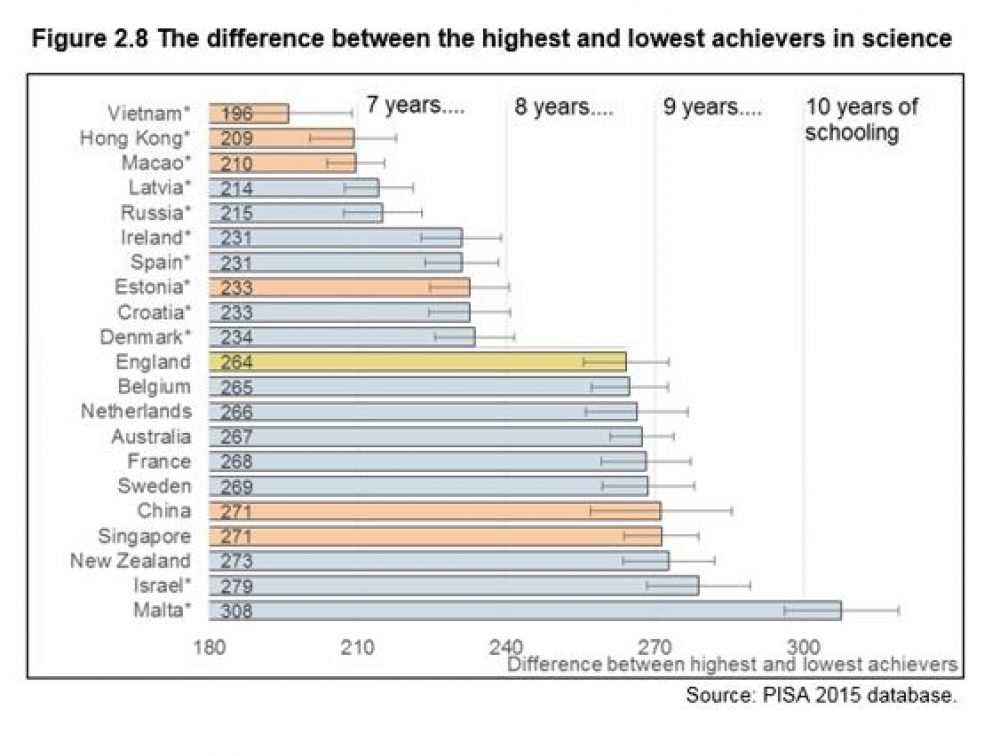

Pupils scoring in the bottom 10 per cent of the Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) are nearly nine years behind in science – and just over eight years behind in maths – than those in the top 10 per cent, according to data released this morning.

Of countries with similar average scores, only four had bigger gaps for maths than England, and only two in science.

Much of the gap is accounted for by socio-economic disadvantage, with pupil performance also differing depending on whether they attended independent schools, grammar schools or comprehensive schools, said a national report by the Department for Education (DfE).

Yet despite the DfE report stating that the PISA data “provided little support” to arguments that academic selection boost the progress of the most disadvantaged pupils, ministers said the PISA results support plans for more grammar schools.

There’s little evidence disadvantaged pupils are more likely to succeed when academic selection used

Nick Gibb, minister for schools, said in a statement: “Today’s findings provide a useful insight as we consider how to harness the expertise of selective schools in this country in the future.

“We know that grammar schools provide a good education for their disadvantaged pupils, which is why we want more pupils from lower income backgrounds to benefit from that.”

The government report said the data shows England has “some of the best young scientists in the world”, with only nine countries significantly ahead, but the high-performing cohort is drawn disproportionately from the country’s independent fee-paying schools and its selective grammar schools.

Independently-schooled pupils made up 23 per cent of PISA “top performers” in science, despite making up only seven per cent of the population. Pupils at selective state schools made up even more than the independent sector, at 32 per cent for the top end of science.

By contrast, “low performers” made up nearly 20 per cent of pupils at comprehensive schools by PISA science standards. Pupils from the most socio-economically disadvantaged 25 per cent of families were also behind by almost three years’ worth of schooling than their counterparts in the top 25 per cent.

Yet the report warns that, since pupils’ prior achievement before attending a certain type of school is not accounted for, the results “cannot be interpreted as providing evidence of school effectiveness”.

Moreover, the argument that selective school systems may help pupils overcome their low socio-economic background is not upheld by international comparison, according to the DfE’s own report.

“We have investigated how the socio-economic gap in 15-year-olds’ PISA scores compares across selective versus non-selective school systems. There is little evidence that pupils from low socio-economic backgrounds are more likely to succeed against the odds when academic selection is used to sort pupils into different secondary schools.

“In fact, the opposite may be the case; in countries where academic selection is prominent, the socio-economic gap in science scores tends to be greater.”

The report also stated there was little support for the “notion that pupils from disadvantaged backgrounds are more likely to succeed if they live in a country with an academically selective secondary education system”, based on the OECD’s definition of resilience [which measures how many pupils in the bottom quarter of socio-economic status are in the top quarter of attainment].

The report continued: “Rather, if anything, the opposite may hold true – countries with more academic selection into secondary schools have the same amount of, or fewer, resilient pupils.”

Countries with low levels of selection, such as England and Canada, have similar levels of pupils who attain strong academic results despite their socio-economic disadvantage, as countries with highly selective systems such as Germany, according to the data.

Gibb (pictured right) added: “We have set out plans to make more good school places available, to more parents in more parts of the country. This includes scrapping the ban on new grammar schools, and harnessing the resources and expertise of universities, faith schools and independent schools.”

PISA, which is led by the Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development (OECD), tests 15-year-olds every three years in more than 70 countries on their ability to apply academic knowledge to real-life situations in science and mathematics, as well as their reading and collaborative problem solving skills.

In England, PISA was conducted from November to December 2015 with a sample of 5,194 pupils from across 206 schools, with roughly the proportion of each school type represented.

£12m pot for science teaching announced

The government has also this morning announced a £12.1 million investment to support the teaching of science in schools until 2020.

The pot of cash will support continued professional development for science teachers, support schools to share best practice and offer tailored in-school support.

The programme will be delivered through a network of national science learning partnerships and also support schools to encourage more teenagers to take GCSE triple science – physics, chemistry and biology.

The government pointed to PISA data that showed more than a quarter of pupils (28 per cent) in England hope to be working in a science-related career by the time they are 30, a “significant increase” compared to 16% in 2006.

Gibb added: “Studying science offers a wide range of options following school – whether that’s a career in medicine, engineering or teaching science in the classroom these are the vital skills needed for the future productivity and economic prosperity of this country. This extra funding will further support high quality science teaching in our schools.”

Save

Your thoughts