The government’s decision to freeze pay for most teachers means experienced staff will earn 8 per cent less in real terms next year than they did in 2007 before the financial crisis, the Institute of Fiscal Studies has warned.

Ministers confirmed this week that only teachers earning less than £24,000 outside London or below slightly higher thresholds in the capital would receive a £250 pay rise next year, meaning the vast majority of teachers are ineligible.

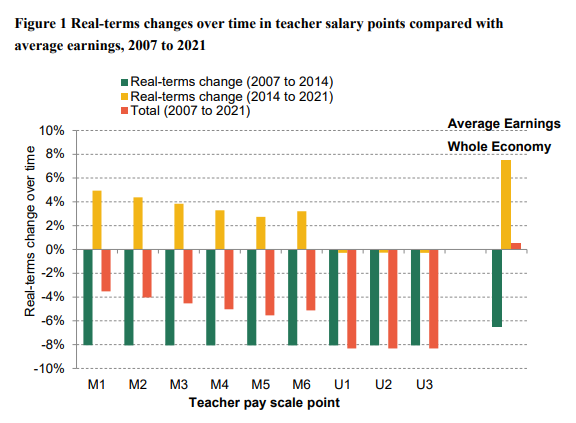

Analysis by the IFS found that as a result of the decision, pay levels for teachers on the upper pay range, around half of the profession, will have decreased by 8 per cent in real terms between 2007 and 2021.

Over the same period, pay for those on the main range will have fallen by between 4 and 5 per cent in real terms, despite recent increases in starting salaries.

In comparison, average earnings across the whole economy will have risen by around 0.6 per cent in real terms since 2007.

Researchers found most decreases in teacher pay over the past 14 years resulted from pay freezes and caps implemented between 2010 and 2014.

The IFS said there were “clear signs” that these pay drops “have been associated with a worsening in teacher recruitment and retention, particularly since about 2015”.

While the pandemic has provided a “temporary improvement”, there are “already signs this is starting to fade”.

The government froze public sector pay in 2010, and rises for teachers were capped at 1 per cent from 2013 until 2018.

Pay rises of 3.5 per cent for newer teachers and 2 per cent for experienced staff were announced for 2018-19, while a 2.75 per cent across-the-board rise implemented in 2019-20.

Last year, the government announced a further 5.5 per cent rise for newer teachers and another 2.75 per cent increase for others.

These rises have led to a 5 per cent real-terms increase in starting salaries between 2014 and 2021, the IFS said, and this was mainly driven by the 2020 rise to move towards the Conservatives’ pledge to increase starting salaries to £30,000 by 2022-23.

However, the government confirmed last year that its pay freeze meant the pledge had been pushed back a year, and will now not be met until 2024.

The IFS said while there was “some logic” for the public sector pay freeze this year, it “does not seem sustainable or wise for 2022 and beyond”.

It comes after the school teachers’ review body also warned that a pay pause of more than one year “risks a severe negative impact on the competitive position of the teaching profession”.

Luke Sibieta, IFS research fellow, said it was “astounding” teacher pay levels remain “so far below what they were before the financial crisis”.

“The fact that it has taken a global pandemic and economic crisis to ease the pressures on the teacher labour market illustrates the scale of the challenge.

“To stop these problems getting worse, the government will need to provide above-inflation awards from 2022 onwards.”

IFS said if starting salaries did reach £30,000 in 2023, they would be about 8.5 per cent higher in real-terms than in 2007.

While it only equates to annual growth of 0.5 per cent per year over 16 years, the increase will “probably still be faster than average earnings over the same period”.

But unless salaries for experienced teachers grow by 13 per cent in cash-terms over the next two years, they will still be lower in real terms than in 2007. The IFS said this was a “remarkable squeeze on pay over 16 years”.

Paul Whiteman, general secretary of school leaders’ union NAHT, said government “must pay as much attention to retention as to recruitment” to keep great teachers in schools and “take action to create a truly positive proposition for a long-term career in teaching”.

A Department for Education spokesperson said the pause to pay rises “ensures we can get the public finances back onto a sustainable path after unprecedented government spending” on the pandemic.

The DfE said while it remains committed to increasing the teacher starting salary to £30,000, progress “towards this commitment will be slower”.

Has implications for pensions for older teachers- I just found out I should have retired last year, aged 57, as my pension has decreased in the last year. Reason is that due to zero or below inflation wage rises over the last ten years, I was actually earning more in 2010 than now when index linking is taken into account. Main part of my pension is based on best 3 years in last ten and I have just moved out of my best 3 years, which, with index linking were the years around 2010. Not a great way to retain experienced teachers.

Also has implications for pensions for older teachers- I just found out I should have retired last year, aged 57, as my pension has decreased in the last year. Reason is that due to zero or below inflation wage rises over the last ten years, I was actually earning more in 2010 than now when index linking is taken into account. Main part of my pension is based on best 3 years in last ten and I have just moved out of my best 3 years, which, with index linking were the years around 2010. Not a great way to retain experienced teachers.

The government does not want to increase wages of experienced teachers because it does not want to retain them. I am quite convinced it is a ploy to get out of paying pensions to teachers.

When schools effectively privatised education through academisation it was the end of fair pay and conditions for teachers. Too many stories of experienced teachers being forced out to reduce pension deficits – or simply becoming too expensive. Furthermore new staff are coming into the role solely for the amazing financial initiatives laid before them, but sadly a shocking number withdraw from the profession within 3-5 years.

It surprises me how as a profession we go from being indispensable to being castigates and vilified depending on the mood of the press and political establishment. Since the advent of academisation education has meandered its way towards a quasimarketised system with MAT’s driving down costs to achieve an acceptable level of education as cheap as possible. We have one of the least experienced teaching populations in Western Europe. The unions are spineless and toothless we a barely audible voice so there is no surprise to see the figures quoted here.