Less than one in four primary pupils reached the expected standard in science last year, according to figures buried in a data release at the end of the last academic year.

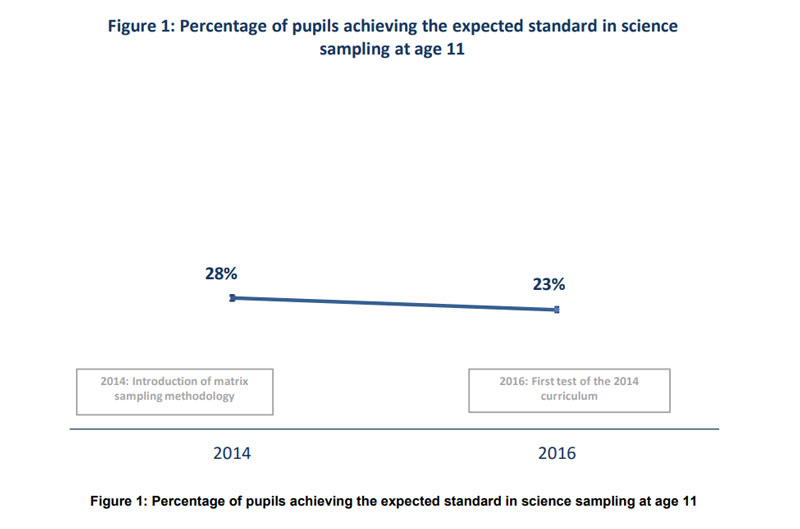

In July, the Standards and Testing Agency released the key stage 2 science sampling results for 2016, which showed that just 23 per cent of 11-year-olds were performing sufficiently well in science. This was down from 28 per cent in 2014.

The test is taken by a small sample of key stage 2 pupils to monitor national performance in science.

Allana Gay, deputy headteacher of Lea Valley Primary School, said the results demonstrate that science is “the poor cousin to reading, writing and maths”.

“While the curriculum for science encourages an excellent foundation, as long as it is not a target-measure for schools, no improvement is expected,” she said.

The sampling method is simply “too random”, she claimed, and schools are “willing to hedge their bets that they will not be tested”.

Science is never going to have the same focus, teaching time or scrutiny

The limited time given to science compared to English and maths can also mean it is hard to drive top results, according to Ian Goldsworthy, a year 6 teacher and science coordinator at Oakmere primary school in Potters Bar.

“All the focus is driven through what has to be done in maths, reading and writing,” he said.

“While the assessment burden is always pointed in the direction away from science, science is never going to have the same focus, teaching time or scrutiny.”

The sampling showed a marked drop in chemistry performance for both boys and girls, which the STA put down to the fact that it is taught in years 3, 4 and 5, but not 6.

This could mean pupils did not receive “chemistry teaching in year 6, nor might they have experienced the new chemistry curriculum in full”, it said.

Biology results for boys and girls were similar to the prior round, while in physics boys outperformed girls and did better than in 2014, but girls did worse.

Pupils were also assessed on “working scientifically”, in which girls did better.

A random sample of approximately 9,500 pupils across 1,900 schools participated in the latest round of the biennial assessment, in which they took different combinations of test booklets.

Marianne Cutler of the Association of Science Education, said she was “not unduly worried” about the results and supported the methodology, which needed time to “embed”.

She pointed out that several factors could be influencing the results, including children realising the tests are “low stakes”, compared to maths and English SATs.

Jane Turner, the director of Primary Science Quality Mark, said the results “need to be looked at alongside the teacher assessment data”, which can cover “a much broader range of evidence” from the classroom.

“It’s clearly indicative of children not being prepared for a test, I don’t think it is indicative of children’s capacity in science,” she said.

The results contrast with the sharp increase in performance seen in English and maths at key stage 2, which has been touted by the government as an indicator of genuine progress in learning.

A DfE spokesperson told Schools Week: “These results represent a snapshot of national performance in science at key stage 2. They should not be used to judge individual pupil performance or for school accountability.

“We want all children to have the opportunity to enjoy science which is why it is a compulsory subject from key stage 1 to 4.”

The current sampling methodology was brought in 2014, after the introduction of the new national curriculum. The next round is expected to take place in June 2018.

Your thoughts