Education’s best-known illustrator, Oliver Caviglioli, is a one-time Olympics trainee, bodybuilder, sandal-wearing PE teacher and son of a Corsican communist. He talks to Jess Staufenberg about quitting headship for his pens

Oliver Caviglioli is one of the only people I instantly recognise on Twitter from a logo-like drawing of themselves, rather than their actual photo. So I’m not sure what to expect on my screen when an inquisitive face in trendy glasses looks curiously back at me, surrounded by evidence of a love of design.

A Stuart Davis painting (an American modernist) hangs beside him, and an abstract hanging mobile spins overhead. Caviglioli crackles with energy and barely draws breath in over one hour of us talking.

You may know Caviglioli for his illustrations in education books, most recently in collaboration with teacher Tom Sherrington. His standing desk is where the magic happens – on a 27-inch Mac, at home in Basildon, Essex, where he grew up. A career move from special educational needs headteacher to illustrator already sounds like a fascinating story, but I’m not prepared for quite how fascinating.

“I was born in Algeria to a French Corsican father and a Scottish mother,” he begins. “My mother had escaped her upper-middle-class background to live with this bearded, divorced, communist. And my father was politically active in supporting the liberation of Algeria from French oppressors.”

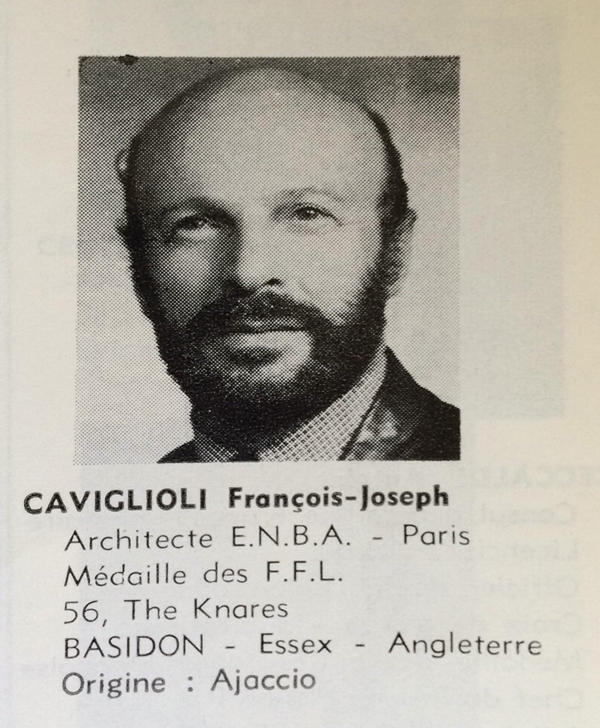

Caviglioli’s father was an architect, doing drawing work for the mujahideen who were fighting the French Army – “it’s work that would have got him arrested, if not murdered, if he’d been discovered”.

Caviglioli was only young, but some of his siblings – he has two sisters and a brother – remember his parents destroying his father’s work in haste one day, and applying for British citizenship. Caviglioli found himself relocated to Basildon, aged just four, with a “well-known communist” for a father.

“We know all about McCarthyism in America, but we forget what was going on here. He found it very hard to get a job.” To make things tougher, his father couldn’t speak any English, and so extraordinarily, when he got a job at the University of London, his mother rewrote his lectures phonetically, so he could read them out loud, non-comprehending, in his thick French accent.

The family were outsiders in their new Essex neighborhood, and Caviglioli was a “mini anthropologist”, as he puts it. “I went to school and they didn’t understand what I said, and I looked different – I had hair over my ear, and theirs was short. I didn’t understand the habits.”

But standing on the outside and looking in, with a critical eye, would go on to define him. As do his parents’ values.

“Everything was subject to aesthetic evaluation,” he explains. “Everything: newspapers, clothes, socks, TV programmes. It would be, ‘that’s too big, they should have done it like this.’” Caviglioli recalls with admiration his father’s design abilities.

Everything was subject to aesthetic evaluation

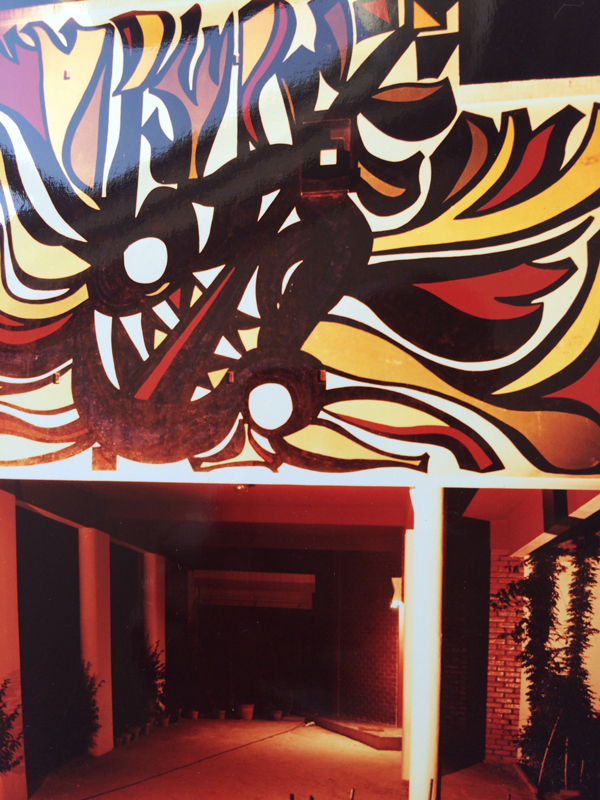

The light switches, for instance, were in the skirting boards, so that if your hands were full, you only had to nudge it at foot level. All the doors slid back into the walls. His father even made a huge mural of Yuri Gagarin’s flight into space in the house, which “completely bamboozled” visitors.

It explains why, when a tree crashed into his garden as an adult, Caviglioli sought a way keep it as a work of art.

“I was used to looking in different ways. There was a domain called creativity, and you carved that out.”

This influence, coupled with the 1960s hippie movement, would lead Caviglioli to seek out unusual contexts. At grammar school, he and his peers followed an “alternative curriculum” of their own devising, he says, bringing in records and reading Marx, psychologists and philosophers.

When his schooling ended, Caviglioli tried out everything from training for the Olympics to becoming a bodybuilder in a “shady underground gym”. Eventually, a nudge from his languages teacher mother saw him join a teacher training college in Brighton, doing PE and French.

“I hated the culture in the PE department – it was like the bloody army.” Caviglioli has a delightful way of phrasing things in extreme terms, while sounding completely even-keel and entertained at the same time. “They had no regard for anyone not PE-oriented.” His popularity with the PE staff wasn’t helped by him wearing flares and bright green sandals.

But then he got a job in a special educational needs school, and “suddenly my view completely changed”. In those days, “it was like a circus – no rules, no curriculum, nothing. It was embarrassing”.

But Caviglioli had found a domain of creativity. By 1994, he was headteacher at Woodlands special educational needs school in Chelmsford. The passion with which he talks about it is infectious.

One enjoyable aspect of Caviglioli is he does genuinely defy categorisation in the tribal world of education beliefs. At first, he tells me how working with pupils with additional needs led him to become “obsessed” with cognitive science, an interest that deepened further when his son was born with Down syndrome. But this hasn’t made him a zealot for a knowledge-retrieval-oriented curriculum.

“I think the only criteria for special needs schools is post-school life. I recognise that in mainstream school, learning something and parroting it back is bloody useful, because it gets you through exams. But it has absolutely no value in special schools.”

Instead, Caviglioli introduced a curriculum in which pupils built up “evidence of success” of them applying their learning in real-world situations, through videos and annotations. “Everything else I did subsequently, which brought me more fame and fortune, was nothing compared to the profundity” of that work, he says.

And it speaks for a wider system issue, too. “I suggest we take seriously an educational trajectory that is not heading towards university.”

He points to the “magnificent” work done in FE colleges with students “hurt and disenchanted with their experiences in mainstream schools”, and says we are “lily-livered” around allowing pupils earlier choice about their education pathways.

“The conversation about cultural capital is a legitimate conversation, but it is at the expense of other more tractable conversations. We harm children by refusing to make a choice sooner.”

But after ten years there was “too much admin” in the headteacher role, says Caviglioli, and he went firstly part-time, and then in 2004 left the role altogether, to pursue an interest in writing and illustrating books. His first two books, called Mapwise and Thinking Skills & Eye Q, were on visual teaching strategies.

There’s this phenomenon of teachers buying books and never getting round to reading them

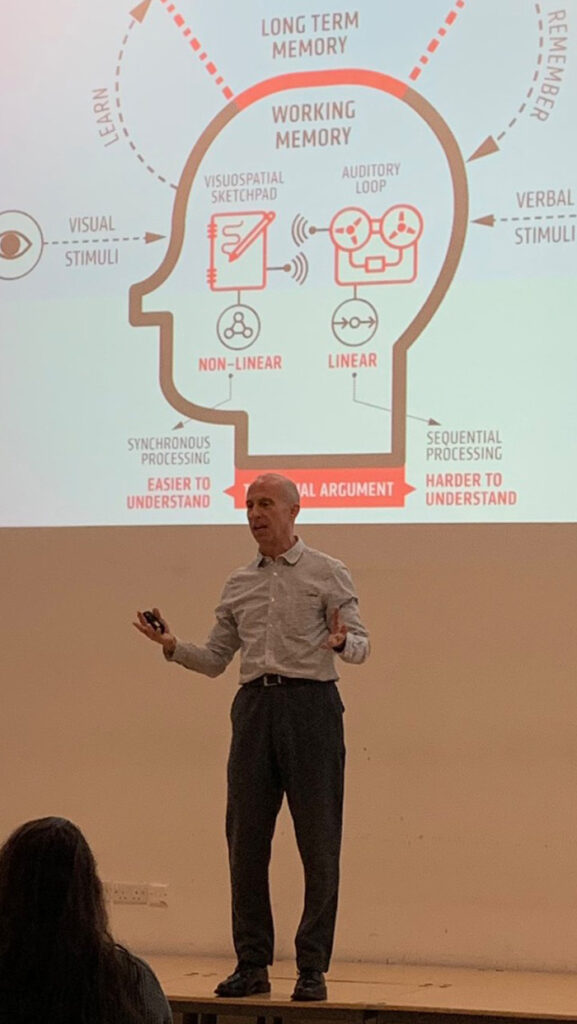

Then he developed the ‘How To’ series, which depicted different teaching techniques, and also wrote and illustrated his Dual Coding With Teachers book, which shows teachers how to combine words with visuals in their teaching.

A key drive for Caviglioli has been subjecting books for teachers to the keen “aesthetic evaluation” he learnt as a child. “We all want teachers to be evidence informed, but there’s this phenomenon of teachers buying books and never getting round to reading them. Obviously there’s something wrong with the books!”

So Caviglioli studied magazines such as Wired and Monocle for inspiration on page layout, noting the “aspirational” and non-patronising style of the content. “I was in pursuit of the magazine-ification of books,” he grins. The work lets him join up his multiple loves: cognitive science, teaching and aesthetic perfection.

I was in pursuit of the magazine-ification of books

The approach has clearly worked. The first two volumes of the popular ‘WalkThru’ series with Tom Sherrington (the third is out next month) give “modules” of teaching techniques. Each is illustrated so the teacher can clearly remember the approach, such as ‘checking for understanding’ or ‘cold calling’ on pupils for answers.

The idea, says Caviglioli, is that an A-level teacher in school, or a teacher of horse husbandry in FE, both have a common language to discuss the “core essentials” of teaching, no matter their context. Now 2,000 organisations use the WalkThru volumes, across 36 countries.

From headteacher to illustrator, Caviglioli is by far one of the most interesting interviewees I’ve sat down with. It only seems a shame he’s not still leading what would presumably be the most colourful special educational needs school around.

Yet his blunt response that “too much admin” caused him eventually to leave headship shows that even outside mainstream, the domain for creativity is squeezed in teaching. Caviglioli has moved to a space where he is freer – and able to explain how other teachers can be, too.

Your thoughts