Mums returning to teaching from maternity leave are more likely to stay in their jobs if they work part-time, a major new study suggests.

It also reveals how the first 12 months back are crucial for retaining new mums.

The Key Group report – believed to be the first large-scale study into what happens when teachers return from maternity leave – also found mothers are less likely to quit in the medium-term than their peers.

The study was based on 150,000 teachers across a four-year period at more than 6,700 schools in England, including nearly 3,000 teachers who went on maternity leave.

Part-timers more likely to stay

Overall, teachers starting maternity leave in 2020 were slightly less likely to leave their school over the following four years (39 per cent), compared with all teachers (42 per cent). This includes teachers who move to another school, rather than leave the profession.

The leaving rate dropped to 32 per cent for returners who worked part time. This went up to 45 per cent for those who went back full time.

Researchers say this suggests that offering part-time roles is “one way to retain females, and to retain them at higher levels than average”.

Women in their thirties make up the largest single demographic to leave teaching each year, so this should be “prioritised if we want to really improve retention rates overall”, they add.

Nearly one in four of the 40,000 teachers who left the profession in 2022-23 were women in this age group.

Baroness Bousted, a former union boss who now leads the Teaching Commission, says it is no longer “good enough” to put part-time and flexible working in the “too difficult” drawer.

“We need, as a profession, to ask ‘how can we accommodate this request in order to keep our best talent?’”

The north-south and primary-secondary divide

Bridget Phillipson, the education secretary, has previously said she is “really concerned” about the number of experienced women, particularly those in their 30s, who leave teaching because they find it too difficult to combine work with family life.

The report found big differences between school type and location. Thirty-one per cent of all teachers in the study worked part-time in the south west, compared with 16 per cent in inner London.

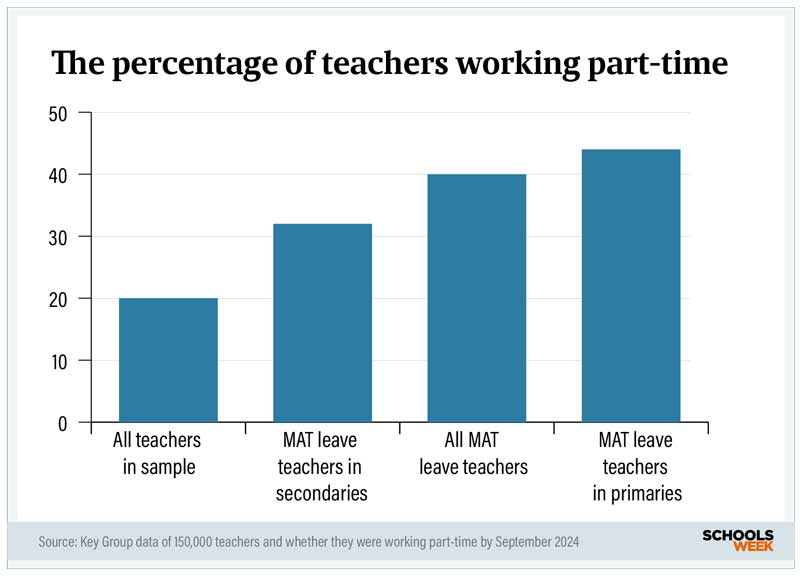

Returning mothers were twice as likely to work part-time (40 per cent compared with 20 per cent of all teachers), with discrepancies between returners in primaries (32 per cent) and secondaries (44 per cent).

Matt Crawford, the chief executive of the Embark Federation, says timetabling could be a hurdle. “It’s much easier to accommodate part-time teachers in primary, where you can run job shares, or slot an SLT [senior leadership team] member into a class.”

Its is more difficult at secondary, especially in core subjects that have multiple lessons a week, and where leaders do not like multiple teachers because it makes accountability for GCSE results harder.

Returning mothers working in secondaries had a 43 per cent leaving rate – rising to 60 per cent of the 162 teachers who worked in London secondary schools. The leaving rate was 37 per cent in primary schools.

Meanwhile, schools in the north of England did a better job of retaining staff coming back from maternity leave.

The report flags the relatively higher wages of teachers compared with other sectors in the north, while the high cost of living could be a factor for the poor retention in London.

The hurdle of the first year back

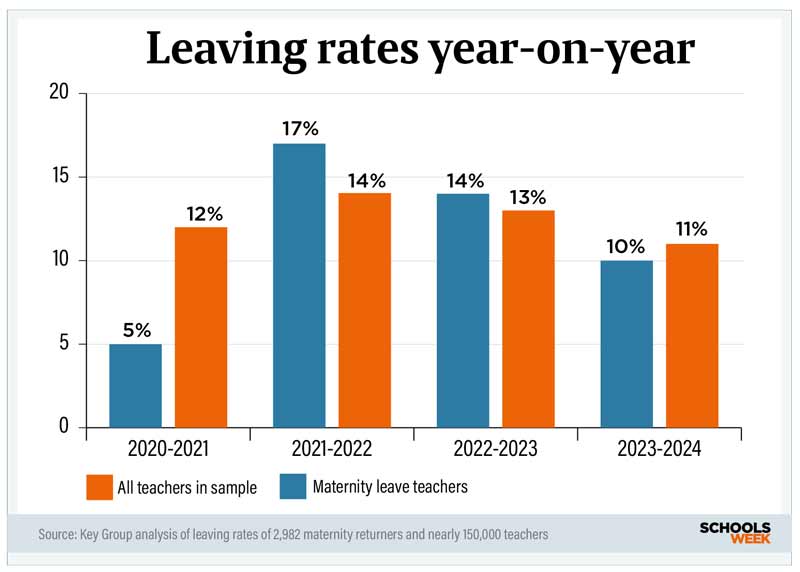

The study found 17 per cent of returning teachers quit within a year of coming back from maternity leave, five percentage points higher than the leaving rate for all teachers.

However, if they stayed more than a year the rate dropped to just 10 per cent in later years.

Emma Sheppard, the co-author of the 2024 Missing Mothers report, says the first year back is when women are “particularly vulnerable to leaving. Even when working in the most supportive of schools, this is a period of huge change that requires understanding and flexibility from employers.”

One-to-one and group coaching could help schools support mothers to “navigate the necessary compromises and find harmony between their home and school lives, without reaching breaking point in either sphere”.

Anna McShane, the director of The New Britain Project, an independent think tank, says teaching is “haemorrhaging” experienced women because it failed to accommodate the “basic realities of motherhood”.

The Missing Mothers report found mothers in their thirties cited excessive workload, family commitments, and lack of flexible working arrangements as their reasons for leaving teaching.

Leadership FOMO

The lack of flexible working in leadership is another hurdle, with 31 per cent of female classroom teachers working part-time compared with just 8 per cent of heads.

Shanti, a year 3 teacher with two children, works three days a week in a job-share. “I wouldn’t be able to do my job if it wasn’t part-time – I couldn’t make it work practically,” she says.

“But I do worry that it’s impossible to climb the ladder as a part-time teacher and that makes me feel stagnant.

Jonny Uttley, the chief executive of The Education Alliance, says many part-time teachers “have to give up hopes of progressing to leadership. Far too many great female teachers with leadership potential do not progress once they go part-time.”

But Uttley says his trust has three heads working four-day weeks, with a deputy stepping up on the fifth day. “This is great leadership training in itself.”

Claire Heald, the chief executive of The Cam Education Trust, says it can “sometimes be easier” for mothers to fill leadership roles because therein be more flexibility than a a full timetable of classroom teaching.

The report also calls for all trusts and schools to evaluate their retention data and offer part-time working to all returning mothers.

They should also advertise vacancies as “being open to flexible working, part-time working and job shares”, and to consider termly updates to the timetable to accommodate those making requests throughout the year.

Your thoughts