In 2017, the government passed a law forcing every organisation with 250 or more employees to publish specific figures about the difference in pay between genders, both on their own websites and on gov.uk.

The stats had to include both the mean and median gender pay gap, the proportion of men and women who have received a bonus payment, the mean and median gap in these bonuses, and the proportion of men and women in each quartile pay band.

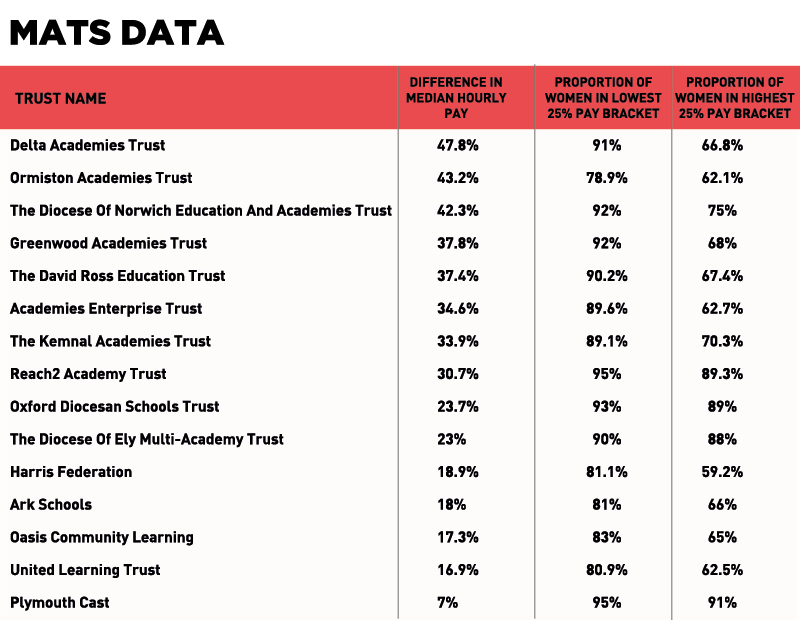

Schools Week took a detailed look at the gender pay gap at the 15 largest multi-academy trusts in England.

Men’s pay for was higher on average than women’s at all 15 of the MATs we investigated.

Delta Academies Trust, in the north, had the largest difference in median hourly pay between men and women, the latter earning a salary that was on average 47.8 per cent lower than men’s.

The government’s statistics do not state what the average salary is in any business – but at this rate, if the average rate of pay for male employees were £50,000 a year, women would earn just £26,350.

The average pay gap across all 471 of the academy trusts which had submitted their data by the start of April, was still huge, at 31.7 per cent in favour of men, according to research by Education Datalab, making Delta’s gap appear starker in contrast.

However, the trust – which runs 43 schools – also reported more women among its top 25 per cent of earners, outnumbering men two to one. On the other hand, women also make up a huge 91 per cent of the lowest pay quartile.

A spokesperson insisted every employee is paid an equivalent salary for the same job.

“Employment opportunities are open to all staff across all quartiles. The employment opportunities within the lower pay quartile are often part-time or term-time roles,” they claimed.

“These roles are open to both men and women. We are looking to further analyse the data to look at the impact of part-time and term-time roles on the reported headline figures.”

Plymouth CAST was the best of the 15 largest trusts, with a median gender pay gap of only seven per cent.

It runs 36 Catholic schools, most of which are primaries, throughout the south-west of England, and is led by interim CEO Dr Karen Cook.

CAST’s top pay quartile was 91 per cent female, but it also had a high proportion of low-paid female staff, making up 95 per cent of the lowest pay quartile. Schools Week contacted the MAT but did not receive any comment.

Outside of the top 15, the MAT with the overall highest median gender pay gap was Sussex Learning Trust, where women’s average salary is 62.7 per cent less than men’s. The trust runs two primary schools and one secondary.

Across our academies we have 15 teachers on the leadership scale. Eight of these positions are taken by women

Jonathan Morris, the trust’s CEO, said the gender pay gap was “merely a statistical measure” and claimed SLT’s figures were influenced by its small size, and that it directly employs a large number of female catering staff and learning support assistants, who attract lower salaries. Many are also part time.

“Across our academies we have 15 teachers on the leadership scale. Eight of these positions are taken by women,” he said.

“The trust recently proactively encouraged our female staff to participate in an important CPD initiative to attract more women into leadership positions across West Sussex.”

He also noted the trust’s commitment to gender-neutral uniforms across its schools.

At the opposite end of the scale, 11 out of the 471 trusts paid higher average salaries to women. PA Community Trust pays women 19.2 per cent more than men on average, though it was nevertheless unavailable for comment.

Angela Rayner, Labour’s shadow secretary of state for education, said the data suggested pay at MATs is “skewed”.

“The government is entrenching inequality in the education system. Ministers’ inability to act on excessive levels of pay has already seen huge pay disparities between hardworking teachers and a tiny minority at the top,” she said.

Bonus round

Five of the 15 largest MATs also reported they had handed out bonuses: Ormiston Academies Trust, The Kemnal Academies Trust (TKAT), Harris Federation, Ark Schools, and United Learning.

Both Ormiston and Harris paid bonuses to over half of women (58.8 per cent and 59.7 per cent respectively), but also to an even larger proportion of men (71.4 per cent and 68.4 per cent).

Ark and United Learning gave bonuses to around five per cent of both men and women, while at TKAT extra cash went to three per cent of men and 1.7 per cent of women.

Harris had the greatest difference in average bonus pay, with a median of 30.7 per cent in favour of men. Women’s median bonus pay at Ormiston was 3.7 per cent higher than men’s, while at United Learning the median bonus pay was equal.

Private schools

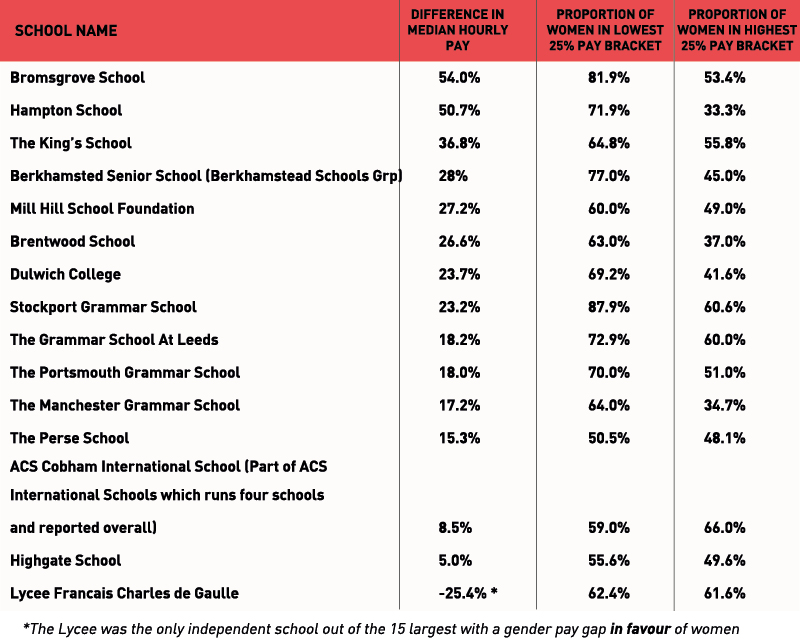

Among the largest 15 private schools by pupil numbers, the pay gap ranged from 54 per cent in favour of men to 25 per cent in favour of women.

Bromsgrove School in Worcestershire, an ‘outstanding’ school that takes children aged two to 18, had the largest gap. For senior school pupils it charges fees of £5,555 per term for day pupils and £12,430 for boarders.

“Many of our support staff roles are attractive to women as we are able to offer term-time and part-time opportunities,” said its spokesperson.

Many of the roles involving pastoral care and support for young children and housekeeping services are more appealing to women

“In addition, whilst we always offer all roles to both genders, many of the roles involving pastoral care and support for young children and housekeeping services are more appealing to women.

“As we have a high number of women employed in these support roles which are paid at lower rates than teaching roles, the overall mean and median pay calculations are misleading.”

Lycee Francais Charles de Gaulle school in London was the only school among the largest 15 to pay women more than men. It had an median gender pay gap of 25.4 per cent.

The school also had an almost even split of male and female staff in the top and bottom pay quartiles. Highgate was contacted for comment but had not responded by the time of going to press.

Seven of the 15 largest independent schools gave bonuses to staff. Manchester Grammar School, a seven-to-18 boys’ school, had the greatest gap, as no women had received a bonus while 0.7 per cent of men had.

At Bromsgrove School, women’s median bonus pay was 53.3 per cent lower than men’s, with one per cent of men receiving bonuses and 0.9 per cent of women.

Brentwood School, a mixed Christian school for three- to 19-year-olds in Essex, had the smallest difference in its median bonus pay gap. Women’s median bonus pay came in at 11.7 per cent lower than men’s. However, the school handed out bonuses to three times as many men as women, with 18.7 per cent of men receiving the perk compared with 6.5 per cent of women.

Schools Week chose to look at the median, or middle, figure when comparing average pay gaps rather than the mean, because it more accurately reflects the experience of typical workers.

A small number of very high paid individuals at the top or bottom of an organisation can skew the mean average and make it higher.

A perfect union?

Two education unions – the National Union of Teachers (NUT) and NASUWT – are large enough to meet the requirement to publish their pay gap.

The pay gap at NASUWT was considerably larger than at the NUT: women’s median hourly rates came in at 42.7 per cent lower than men’s. If NASUWT were included with the largest academy trusts, it would have the third largest gap.

Just over a third of top earners there are women, and around 74 per cent of workers in the bottom quartile of salaries.

“The union’s strong commitment to flexible and part-time working, its extremely high retention rates and the high proportion of women in roles within administrative/secretarial, conference centre and housekeeping functions all have a significant impact on the union’s gender pay gap,” said Chris Keates, its general secretary.

“NASUWT is actively pursuing strategies to increase the representation of women and other underrepresented groups in the lay structure of the union, as this will contribute to more women applying for senior posts.”

For the NUT, women’s median hourly rate was 16.6 per cent lower than men’s – losing an equivalent of 17p from each pound.

The highest pay quartile contained more women than men at 58.5 per cent, but the lowest quartile was also female-dominated, at 86.6 per cent.

“Equality is vitally important to our work as a union. But our gender pay gap is bigger than we would like it to be,” said a spokesperson.

“The challenge for us – as it is across Great Britain – is to eliminate any gender pay gap.”

Teach First

Education charity Teach First had an impressively low gender pay gap; women’s median hourly rate was only 2.7 per cent lower than men’s. There were around the same percentage of women in the top and bottom pay quartiles, at 67.4 per cent and 65.9 per cent respectively.

“While we’re pleased our pay gap is comparatively small, we can’t rest on our laurels. Our aim is to eliminate the gap completely,” said a spokesperson.

Teach First has taken steps to improve the situation, she added, such as reviewing the pay structure and providing equal access to career development opportunities.

“We have a longstanding commitment to flexible working policies for all staff – for example job shares, flexible hours and remote working – to enable our staff balance work and life. From this year, we will offer shared parental leave to all employees.”

The organisation also plans to introduce blind recruitment and train hiring managers to minimise unconscious bias.

I’m genuinely impressed by Schools Week reporting on the position at the NUT and the NASUWT. The explanation they give is very similar to that given by some of the academy trusts, but it doesn’t seem to be subject to the same degree of cynicism (nationally that is).

However rather than simply producing an article that crunches numbers from the publicly available data, like so many other media outlets are doing, why not do some real journalism and look to put this into the context of the education sector?

As I’ve commented on elsewhere, in primary education we have a massive imbalance in genders. I’ve seen reports that talk about how men only make up 10-15% of primary teachers, and that 25% of primaries have no male teachers at all. I’d bet the figures for primary TAs are even more imbalanced, let alone catering staff (if not outsourced) In an organisation that includes primary schools, given these figures it seems almost inevitable that there will be a gender pay gap.

To my mind the two main questions are about equality (are men and women paid the same amount for the same job), and opportunity (are men and women given the same opportunity for advancement if they want it). I don’t think the current focus on headline figures within gender pay gap reports, without the deeper research, helps.