Alternative provision and pupil referral units are never far from the headlines.

One of those headlines in June this year – “Inside pupil referral unit where ‘unteachable’ kids as young as FIVE often ask teachers for a hug” – was about Marie Gentles’ school.

We have to do more to support mainstream staff to get behaviour right

The head of Hawkswood primary PRU in Waltham Forest, east London, was the only leader (dozens were asked) who allowed journalists in as part of The Sun’s investigation into children in PRUs, some supposedly as young as two, as a result of exclusion.

“The original headline was just awful,” Gentles says. “It also used the phrase ‘sin bin kids’.” As part of her visit, the journalist had been allowed to speak to a child and see his work. “His mum was devastated. It took months supporting her to get that title changed.”

Two years earlier BBC journalists had been invited in too. So what’s behind such openness?

“Anyone who knows me will tell you I’m not a media person,” Gentles says with genuine laughter in her voice. “In 2017, I’d recently taken over as head – we had a new executive head too. But the previous incumbents had arranged to do The Victoria Derbyshire Show. We were committed.”

On the day Derbyshire tweeted: “She’s opened up her school to us today, giving us incredible access. She’ll talk to us about the kind of techniques – including restraint – that help turn a child’s life around.”

“It turns out they really got the message, about the misunderstanding of PRUS and the children in them,” Gentles says. “We got so many messages of support from parents and other schools. We had visits from Holly Branson, Princess Beatrice and the Rev Rose Hudson-Wilkin, and we got carried away. We thought we’d changed those perceptions.”

The experience with The Sun, specifically that headline, changed that view.

The school has since turned down an approach from Channel 4, but Gentles is determined that things will change, in perceptions and policy.

Despite the Timpson review’s call for a shake-up of the sector – and former education secretary Damian Hinds accepting all its recommendations “in principle” – there have been few policy changes.

Not content to wait for politicians to act, in January Gentles will leave Hawkswood with one of her deputies, Katy L’Aimable, to set up a behaviour consultancy to work with schools, parents, police and social care.

She will also be joining The Difference, developing a new leadership pathway for teachers dedicated to improving outcomes for the most vulnerable learners. Its existing leaders’ programme recruits mainstream middle and senior leaders to spend two years in PRU senior leadership before helping them to return to mainstream with their new knowledge and skills.

“In our current climate,” she says, “we have to do more to support mainstream staff to get behaviour right. However, because of where we are, we also need to invest in PRUs and AP because there’s a growing need for them.”

It’s a case of needing to look at it from a different point of view, she says.

“If we reframe our thinking about what we want for the long term, things look different. There is always going to be a cohort of students who require something else and that’s fine, but if we work on early intervention and prevention, then we wouldn’t find ourselves firefighting.”

Gentles accepts there’s been a lot of progress during her career, but there’s a long way to go and she has a few ideas.

“I did a four-year teaching degree. I was at a really nice teaching school, but I can’t remember a single thing we did on behaviour. We should have behaviour training every year just like we have safeguarding training.”

Because we don’t, she says, we still treat the behavioural and the academic separately. “We get visitors who’ll look at our timetable and they’ll say that’s great, but we can’t do that at our school because the behaviour isn’t good enough. That’s where it’s gone wrong.”

The Timpson review said improving PRUs should be a matter of urgency. To make that happen, Gentles says, those sometimes uncomfortable conversations need to happen. “Historically we were so segregated. When an email went out about borough sports day, we would never be included in it. We fought for that. It can’t be about those children and these children, but our children.”

That segregation was never right, but Gentles points out that today’s challenges, like county lines, don’t discriminate and make partnership all the more pressing.

That’s also why she can’t be contained by a single role anymore. Gentles spent her first seven years at Hawkswood as its deputy head, the past three as its head, and she feels she couldn’t be leaving it in a better place. An inspection in January this year confirmed the school is still ‘outstanding’, a repeat of a June 2015 judgment.

“I’ll still be serving Hawkswood, but from a different angle,” she says. “I just can’t do it within the capacity of my current role.”

Like most teachers in PRUs, Gentles started her career in mainstream. “It was this lovely little Catholic school with next to no behaviour issues.” From early on, she was one of those teachers with a special touch for challenging behaviour. “When there was the odd child who showed behaviours they would always get sent to my classroom. And then when they came to my room, there weren’t any issues and they got on with their work.”

She didn’t ask for children to be sent to her. They just were – and that was part of the problem, although she did not realise that at the time.

Gentles stayed at that school four years and was promoted to NQT supervisor very early. Through that experience, she says, “I started to recognise that maybe I had a bit of an understanding with children with emotional and behavioural difficulties and additional needs. But I wasn’t quite sure what that understanding was.”

Where that understanding came from says much about the values Gentles attaches to education.

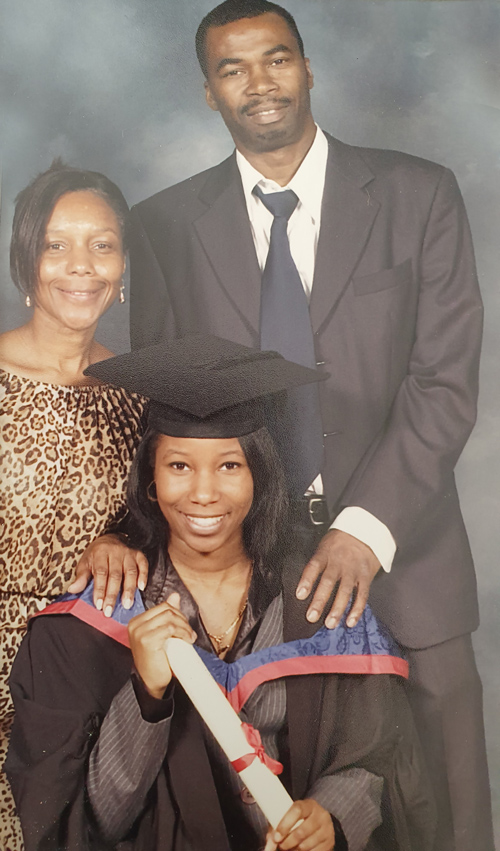

“I had a really good upbringing. Mum and dad were at home. I have an older sister and a younger brother. We lived in a nice home in Highams Park [in east London] with nice neighbours and we went to good schools.

“We didn’t really come across any harrowing stories. We weren’t amongst that,” she says. “But it was normal for us to have adopted and foster children in our extended family.”

Her mother, Jennifer Bancroft, worked in a care home for the elderly, but when carpal tunnel syndrome forced her to quit she became a foster carer. Her mother’s two sisters also fostered.

It was her mother who taught her the value of coupling care with high expectations. This defines her attitude to education and has progressively brought her closer to the most vulnerable children in our school system.

Gentles’ father, Geoffrey, a BT engineer on shift work for most of his career, instilled self-belief in his children. For him that meant the belief that they could go to university and be successful professionals.

“When we were growing up, there was no conversation about it. We all just knew we would go. But there was still enough room for us to just be who we are.”

That unwavering expectation of academic excellence is something Gentles has taken with her throughout her career, and nowhere has it been more transformative than at Hawkswood.

She left her first school for a far more challenging context in Newham, east London. “I threw myself in at the deep end. I don’t know what I was thinking.”

It was the same scenario. A lot of children were sent to her class. “This time, I realised it wasn’t right. I felt we should be working together so that any teacher in that situation should be able to support those young people’s needs.”

Gentles is a mother of two, a 16-year-old son and an 11-year-old daughter. The former is at college, and works at Hawkswood as a volunteer one day a week.

Her daughter’s birth and a move to Waltham Forest made her ready for a new challenge. A job came up at a local PRU. “I’d never even heard of a PRU, in teacher training or anywhere else, but I decided to give it a go.”

She describes her first day, telling the story of a little boy who, in the blink of an eye, went from an angel to having to be physically contained. “I was shocked. This was primary? What is going on here?”

But it didn’t take her long to change her way of looking.

“I had an Australian colleague who said to me ‘you’re exactly what I need here’. Before, it was almost like a glorified youth club. When I started delivering these lessons in my room, the children were making significant progress – regardless of their starting points – and I just thought, ‘Isn’t this what we’re supposed to do?’”

Ten years on, she has changed the actions of everyone in that school, and its students’ results. Looking at PRUs through Gentles’ eyes, I can start to see the steps to resolving the tensions around exclusion, and that’s no mean feat.

There may yet be hope for different tabloid headlines.

Your thoughts