Luke Tryl, Ofsted’s director of corporate strategy, is one of those people who always appears impeccably presented – which is why it’s reassuring, as I smooth down my hair from the cycle ride, to notice that he’s wearing one poppy-red sock and one powder-blue.

He casually crosses and uncrosses his ankles, settled in a low sofa in the office of his boss, Ofsted chief inspector Amanda Spielman, and there’s something about his apparent lack of concern at the mismatch that seems at odds with his nature.

Before I can formulate a polite version of the odd-socks question, though, he fills the silence with a self-deprecating reflection on whether he’s going to “balls up” the interview, which segues naturally into a discussion about the perils of public engagement.

“We’ve been debating a lot internally,” he admits. Given the hot water some of the inspectorate’s employees have been getting into, one would hope this is the case. “We’ve seen how high tensions can run on Twitter and social media, and there’s a danger you get sucked in.”

These debates are all fairly new to Ofsted. Before Spielman took over as chief inspector last year, only HMI were allowed to speak publicly.

Spielman changed all that, says Tryl. “The first thing she did was she said, ‘Well, that’s ridiculous because it means we’ve got a whole research team who can’t talk about the findings.’ So she’s much more keen on people going up there.” The downside, of course, is that “it places a premium on you knowing when to step away – of knowing, actually, that when I’ve been out for a glass wine is probably not the time to engage”.

Tryl won’t talk specifics – and certainly won’t be drawn on the infamous spat, one Saturday evening in September, when Ofsted’s director of education, Sean Harford, told the joint general secretary of the country’s largest education union, Mary Bousted, that it was “impossible, under your leadership, to try to work with your union to improve things for all in education”.

Harford answers directly to Spielman. However, it’s ultimately Tryl’s job, as the senior manager in charge of research and communications, to navigate such issues.

Tryl has experience – he handled most of the press during his two years as special adviser (SpAd) to Nicky Morgan during her time as education secretary.

This means he was somewhat prepared when the Daily Mail ran a smear story last year claiming that he was pushing the LGBT agenda in schools. Based on the fact he used to work for campaigning charity Stonewall, they concluded he was responsible for the inspectorate taking a hard line on two Jewish schools (one of which was inspected before Tryl even joined Ofsted) that weren’t teaching pupils about homosexuality.

What upsets him most – apart from the fact that they didn’t ask him for a comment – was the suggestion that Tryl, who is a practising Christian, had some kind of anti-religious agenda. On the contrary, he believes very strongly that a religion must be able to teach the tenets of its faith. “If they say, ‘In our religion we do not condone gay relationships’, or whatever, they should be able to. As long as they say, ‘But under British law, gay marriage is allowed.’”

Interestingly, when he was a SpAd, he preferred his colleagues to handle anything to do with gay rights – so homophobic bullying in schools, for example – precisely because he wanted to avoid “blurred lines”.

Instead, Tryl – who was previously Stonewall’s head of education – focused on the “what’s taught stuff. So, the sort of Nick Gibb agenda basically”.

Tryl is an acolyte of the Gibb/Michael Gove academic-rigour-for-all philosophy. Like Gove, he was deeply affected by his own grammar school experience. “It genuinely changed my life, that school. They found whatever potential I had and pushed and pushed and pushed. They pushed me to apply to Oxford. They encouraged my reading, got me into debating. It’s a big part of what motivates me now in education. I know you shouldn’t rely on anecdote, but that school transformed my life, and I owe it so much.”

It’s probably best not to engage publicly when you’ve had a glass of wine

Growing up with his mum and two younger sisters on the outskirts of Halifax, he was the first member of his family to go to university. And while he’s not arguing for more grammar schools, he does want everyone to be able to experience the same level of academic rigour he was exposed to.

“I think in terms of equal opportunity for all, if you make all comprehensives really good so that everybody has a chance to move up at them, brilliant. At the same time, what people are now saying is that if you focus so much on curriculum and knowledge, you’re leaving out the kids who just feel alienated by that hard curriculum.”

That’s still no reason to lower standards, he argues, echoing Gibb’s concerns about the dangers of setting low expectations for some children, and defending the schools minister vehemently. “There is no one who cares more about disadvantaged pupils and young people, and it’s because of that he doesn’t want other people writing them off on their behalf,” he insists. And while Gibb understands that not everyone is going to be able to get nines in EBacc, “what he doesn’t want is that you start from the premise of ‘They can never do the EBacc’”.

Another of the reasons he remembers school fondly is that “it just allowed me to be”.

Age 14, Tryl came out at school, and found his peers supportive. “We were in town, and there were some kids from another school who were shouting homophobic abuse, and I remember the guys from the rugby team at my school were the ones who went up to them and told them to shut up.”

One year 7 lesson particularly stands out in his memory: “The teacher said, ‘Oh, I’m going to talk to you about gay stuff because I think it’s important. But you should know, I’m not allowed to by law.’”

This was around 1999, when talking about homosexuality in schools was still illegal. “Then things just went whoof! You’ve got to give the New Labour government so much credit for that: civil partnerships, adoption, repeal of section 28, the Equality Act. It’s amazing.”

A lifelong politics nerd, Tryl named the family chickens after former prime ministers, according to character, so the warring pair were Gladstone and Disraeli. He’s also a lifelong Tory.

“I’m told by my gran that, in 1992, when I was five, I stood outside a polling station telling people to vote for John Major, and she kept trying to shush me up.”

By 14 he’d joined the Conservative party, a move for which he has no credible explanation. His family wasn’t particularly interested in politics. “Apparently I used to like watching the news as a kid,” he says, as if that settles the matter.

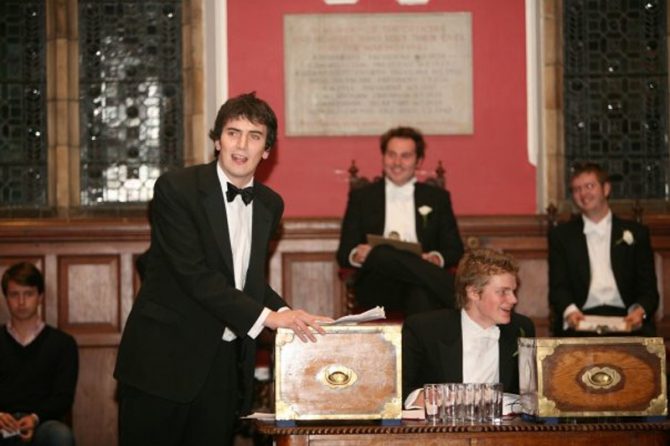

At Oxford University, where he studied history and politics, he focused on the cross-party politics in the Oxford Union, of which he was elected to the prestigious post of president for a term. He has campaigned in every general election since he was 14, so he struggled to stay out of it all in 2017, during his first election as a senior civil servant: “I was sort of biting my nails.”

This was quite a contrast to 2015, when he moved to Loughborough and lived with Morgan for the duration of her campaign. “Lots of ministers are in safe seats, so those SpAds will go work in CCHQ on policy and that kind of thing. Whereas, with me with a marginal seat, it was great fun. There were some less fun moments, like when we were doing morning media round at Salford studios and we turned up at this hotel in the middle of nowhere, and it was me, Nicky and a series of stag dos around us at 11 o’clock at night.”

Since the “brutal” shock of being ousted in the 2016 post-Brexit reshuffle from what he thought was a five-year post, Tryl no longer makes plans for the future. When Theresa May became prime minister, Morgan was called to her Commons office – which is code for “You’re losing your job”, so she texted Tryl to let him know. “We had an hour to leave … even before we cleared our desk, it was announced that Justine [Greening] was taking over, and she was on her way in with her people. It is absolutely brutal. I had such a great time working for Nicky. You hear all these stories of these monster MPs, but she’s just the opposite.

“So I sort of went home, poured myself a strong gin and tonic and thought, ‘What’s next?’”

Grammar school genuinely changed my life

What was next was a brief spell working for the Public Policy Projects thinktank – which he refers to as his “funemployment” period, when he also learned to build habits to avoid professional burnout.

As a way of winding down from the day job, his equivalent of the cryptic crossword is evening classes in economics or undergraduate maths at Birkbeck University. He loves it because “it’s just so different from sitting and writing a speech for Amanda”.

Appointing Spielman as chief inspector was one of Morgan’s last acts as education secretary, and it was a controversial one, overruling the education select committee, which had rejected her unanimously. Six months later, Tryl was appointed to the new strategy role at Ofsted.

Applying for the Ofsted role was a “no brainer” for Tryl, who obviously admires the chief inspector. Allegations that the inspectorate is too close to the DfE are ridiculous, he says, because “we, and Amanda in particular, guard our independence quite jealously”.

There’s a different rumour bubbling away, however, that Spielman is brilliant at appearing to be aligned with the DfE in public, but behind the scenes is on a collision course with ministers over which matters more: curriculum or results. So where will this end? Is she going to try to force Damian Hinds to change school accountability measures?

Quite the contrary, says Tryl, quoting John Patten, the education secretary who created Ofsted, who said they deliberately brought in performance tables and Ofsted at the same time, “so that one could do what the other can’t”.

The inevitable consequence of this, though, is that schools are stuck with having to serve two contradictory masters – and not knowing which one they are supposed to keep happy.

The answer is Ofsted, says Tryl, insisting that Hinds has made this quite clear. “I don’t think perhaps enough was made of it, but when the secretary of state said at NAHT [the National Association of Head Teachers conference in May], ‘The only thing that will lead to a school being converted to an academy, or will lead to a formal intervention from the department, is an Ofsted inadequate judgment.’ It was very squarely saying, ‘Actually it’s us’. So that places a premium on us, taking into account those results, but telling a story around them – to help mitigate Campbell’s law, that any system of measurement will lead to some form of gaming.”

Tryl’s speech is measured and well paced; his sentences thoughtful and well constructed. In fact, he seems far too, well, “together” to have made his sock choice absentmindedly. So what is it? Some kind of statement, or is he just in too much of a rush in the morning?

Originally the latter, he grins. Then once, as Morgan’s SpAd, he got told off by David Cameron’s private secretary for wearing mismatched socks to a meeting. “Being stubborn, I then stuck with it.”

So what would he do if he could only find a matching pair?

He laughs. ”Panic?”

Your thoughts