Sixty-four per cent of pupils achieved the government’s “expected standard” in reading, writing and maths in this year’s key stage 2 SATs, up from 61 per cent last year, according to interim results published by the government.

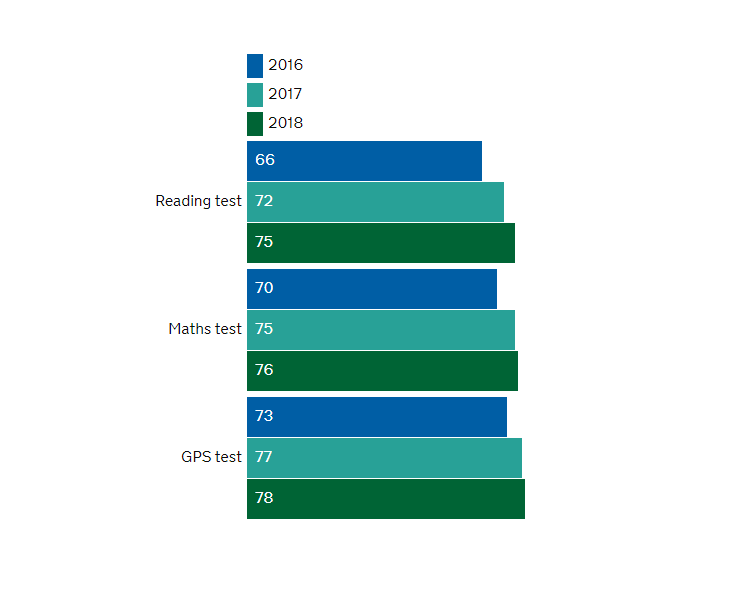

The results show that the proportion of pupils reaching a scaled score of 100 or more rose in every discipline.

In reading, 75 per cent achieved the standard, compared with 71 per cent last year, while 76 per cent met the standard in maths, up from 75 per cent.

In spelling, punctuation and grammar tests, 78 per cent of pupils met the expected standard, up from 77 per cent, and the proportion meeting the standard in writing was 78 per cent, up from 76 per cent.

However, officials warned, changes to assessment frameworks for writing mean that neither the overall results for reading, writing and maths, nor the results specifically for writing, are comparable to those of previous years.

The government also published the marks pupils needed for the 2018 key stage 2 tests to achieve its “expected” scores. You can read about them here.

Nick Gibb, the schools minister, praised both teachers and the government’s reforms for the results.

“A good primary education lays the foundations for success at secondary school and beyond,” he said. “That’s why we introduced a more rigorous, knowledge-rich primary school curriculum – with an emphasis on reading and fluency in arithmetic – to ensure every child is helped to reach their potential from the moment they start school.

“Today’s results and the rising standards we are seeing in our primary schools are the fruit of our reforms and a tribute to the hard work and dedication of teachers across the country.”

But others have criticised the prominence given to the tests and the stress they create in schools.

On the eve of the results’ publication, survey data from the National Education Union showed that nine in ten teachers believe SATs are damaging to pupils’ well-being.

And new research by polling company YouGov for the campaign group More Than A Score found that one in four children believe SATs results will affect their future job prospects.

Julie McCulloch, director of policy at the Association of School and College Leaders, congratulated schools, teachers and pupils on their work and improved results, especially in the face of “harder tests” introduced in 2016.

“They have done a remarkable job in achieving such impressive results,” she said.

“We are, however, concerned about reports of children crying and having nightmares about SATs. Schools do their best to protect their pupils from stress and anxiety, but action is clearly needed to reduce the pressure of the current system.

“The problem is not the tests themselves, but the fact that they are used as the main way of judging primary schools and the stakes are extremely high. In reality, four days of tests out of seven years of schooling can never provide anything more than a snapshot.”

She urged the Department for Education and Ofsted to “attach less weight to a single set of results and to treat these tests as just one element of the story of a school”.

Teachers in turmoil over dud data

Results data for some pupils weren’t factored into the government’s initial SATs data dump on Tuesday morning, leading to inflated overall scores and confusion for schools.

Teachers vented their frustration on Twitter after the blunder saw data on pupils who didn’t sit the tests missed out.

This year the Department for Education calculated the overall results for all pupils in each school, something which teachers previously had to work out for themselves based on individual pupil scores.

Some pupils, such as those with special educational needs, are not required to enter because they are considered to be working below the standard of the tests. However, they are still meant to be recorded in official data using code B.

But an automated system used by the government’s national curriculum assessment tools website, which schools use to access their results, didn’t account for these pupils. This meant schools were given a higher overall score than expected.

School staff spotted the mistake when overall results provided by the DfE did not match up to individual results.

Schools Week understands the incorrect results were subsequently removed from the system and the error corrected.

The DfE was approached for comment.

Is this not just one huge con trick?

The DfE set the scaled score each year so that the % reaching the required standard can be anything they like. The scores MUST go up otherwise the DfE will be criticised in the press, and they will not be able to claim their reforms are working.

KS2 teachers work at delivering something they do not feel is good education, but there is the carrot of a good score for your school, so the teachers play along with this charade.

Look at the graphs. They are repeating exactly what happened at GCSE over 20 years. Scores kept going up, but the children were not better educated. Eventually the Secretary of State will complain about grade inflation and revamp the system and we will start the chase for marks again.

What a futile soul destroying process! It is supposed to be about educating our children not jumping through hoops.

I despair that the profession has fallen for this con trick!