Marcus Shepherd fell in love with teaching by accident and was a principal at just 27. He tells Jess Staufenberg why a super-strong mentor is the key for leadership

When Marcus Shepherd, principal at the Wells Academy in Nottingham, landed the top job, he made an unusual request. He knew behaviour at the school was very challenging and he had an idea.

“I said, ‘Can I do a day as a supply teacher? Don’t tell the kids who I am.’ The thing is…,” he explains to me, “…if the kids know you’re the head, they act differently. So I did a whole day teaching maths.”

It was a chance for Shepherd to be treated the same as any other staff. It showed him the “great things” about the school, where 63 per cent of students are on pupil premium funding, he says – but also the problems.

“It was kids not listening, kids being difficult, kids walking out of lessons. The worst thing in teaching is kids flat not listening to you. It was almost like a lesson was going on but no one had told a number of students it was happening.”

It was a different experience for Shepherd who, remarkably for such a young headteacher (he was only 30 when he took the role), had already been a principal at a previous school. He was used to being listened to, and yet here were distracted students, swinging off chairs. “I thought, if I’m feeling like this, how is the NQT down the corridor feeling?”

It was a situation not far removed from Shepherd’s own experiences as a child. Growing up in Coalville, an ex-mining town outside Leicester, he took his own approach to students disturbing lessons. “If kids messed around, I’d turn around and say, ‘If you want to mess around, do it outside’,” he smiles, before growing serious. “I knew education was it for me. This was my chance.”

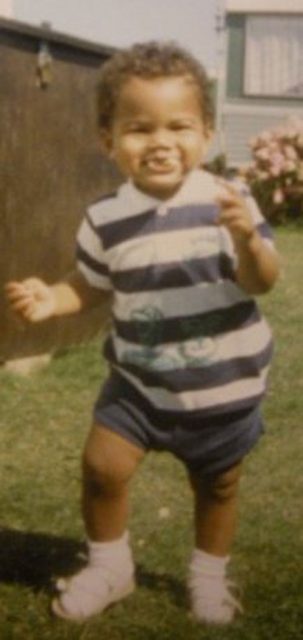

He was up against other people’s assumptions. His mum was a single parent and he was mixed race, on free school meals in a largely white neighbourhood. His mum made absolutely clear to him and his two siblings – no excuses.

“My mum was constantly pushing me to be the best I could be. I had to be well behaved, or I’d be in a lot of trouble. I had a massive drive to be better. She knew a lot of people, and me being one of the only mixed-race kids, she’d say, ‘People will know who you are if you mess around’.”

Shepherd laughs, recalling a time where his school was celebrating his score of 99 out of 100 in a maths test. “My mum said, ‘What did you lose the mark for?’” He grins again. “I look back now and think, she sacrificed pretty much her whole life. She gave up everything to raise us. We may not have had trainers, but we always had school shoes. She was such a strong influence on me.”

It showed. He took maths, further maths, chemistry, biology and physics at AS level and from there got into Bristol University to study engineering.

Those years took Shepherd abroad for the first time, to study in Australia. While out there, the importance of pursuing enjoyable work became clearer. To earn money in the holidays he “was getting up at 5 o’ clock to start on the vineyard until 3.30pm. Then I’d work at the pizza shop from 4pm until 11pm, then I’d start again. I thought, I want to work hard at university so I don’t have to do this as a living. This is tough, tough living.”

After graduating, Shepherd applied for some business graduate schemes, but was left uninspired. In one interview, he asked the interviewer: what do you do? “And they said, ‘I’m a senior executive assistant’, and I said, ‘What does that actually mean?’ And this person said, ‘I’m in charge of a multi-million-pound budget for refuse management.’ So I was like, ‘You oversee the bins.’” His face splits into a broad grin. “I thought, I can’t do this – this is a job that exists so someone else can make money.”

Instead, Shepherd found Teach First. “It was the element of challenge to it. I love it when people set me a challenge. It’s just the motivation I need.” He adds: “I definitely wouldn’t have gone into teaching if I hadn’t found Teach First.”

Speaking to Shepherd, you begin to wonder why there is a retention crisis at all. He buzzes with energy, despite taking on more exhausting responsibility very early in his career than most teachers. He’s clear that in his first headship, aged just 27 at an academy in Derby, he struggled to turn his vision for the special measures school into a clear strategy. But he still managed to move it to ‘requires improvement’, and moved on to his second headship after about two years, joining the Wells Academy in 2019.

Instead, the experience has convinced Shepherd that “having a really strong mentor” is critical for new leaders like himself.

He praises his mentor, Pete Kirkbride, a senior education adviser at Greenwood Academies Trust (which runs Wells Academy), who “comes and challenges and supports me – he’s very hands on. Without Pete, the school wouldn’t be anywhere near where it is now,” explains Shepherd, with real humility. He says leaders can feel they need to “save the world”, and don’t always realise they have “a team desperate to work” for them.

I’m thinking of the NQT down the corridor. Why are so many leaving? I ask. “Like every career, some people realise, this is not for me,” he begins carefully. He recalls about 35 minutes into his first ever maths lesson a pupil named Lauren suddenly saying “‘I get it!’ I remember the look on her face, and I thought, I want to be a principal.” For Shepherd, teaching is his out-of-work hobby. “When I found teaching, I found this thing I would give hours to. I sit at the weekend, and it’s not work for me.”

Inspired by the work-hard culture of his upbringing, and his university education, Shepherd’s school is oriented around these two goals. Returning to the NQT, he notes: “What we say is behaviour management is 90 per cent the responsibility of the leadership team. We have to create that culture. Then we can focus on supporting them to be a great teacher.”

As such, pupils are expected to use “indoor voices” in corridors, walk single-file and line up at all break times. Pupils are expected to have two pens and “perfect uniform”, and lessons use the well-known SLANT technique – sit up, listen, ask and answer, never interrupt, track the teacher. The trick, says Shepherd, is always to give the student a chance to correct themselves and apologise before escalation. More importantly, expectations must always be communicated beforehand. “The fundamental thing to understand is lots of poor behaviour is just because boundaries aren’t clear.”

It wasn’t until I was older, that the penny dropped. My mum was the first leader I had as a kid

Shepherd’s second drive is to make university available to all. “Some people don’t like that we talk so much about higher education, but I want every single child to have the qualifications to do that if they so choose.”

Ofsted are yet to revisit, but Wayne Norrie, chief executive of Greenwood Academies Trust, forwards me his latest emailed feedback to Shepherd. It’s a small insight into the huge network of effort and support that goes into leaders and schools.

“I gave you the challenge last time of turning the ‘honeymoon into the habit’. It’s safe to say you have smashed that one!” Norrie wrote. “I have never seen the academy as good as it was today. The attention to detail, which really moves a school to ‘great’, is there in buckets.”

Has he ever told his mum how she influenced him? I ask Shepherd. “Yes, definitely. It wasn’t until I was older, that the penny dropped. She was the first leader I had as a kid.”

He smiles broadly again. “The culture of my school is very much built on the culture of how she brought me up.”

Your thoughts