The new Ofsted framework has been discussed for months, but nothing brought it into reality like inspectors arriving on the doorstep of one of our schools.

Being among the first to experience the new format has been illuminating – the process is clearer, and in many ways fairer.

But with the need to evidence every criteria within an evaluation area to meet the ‘expected standard’, the bar has certainly been raised.

So, there may be fewer surprises, but the framework demands considerably more from leaders, particularly in the breadth and clarity of the data and evidence they provide.

One of the immediate positives was how closely inspectors followed the handbook.

That gave the visit structure and meant we largely knew what to expect. The tone felt more like a professional dialogue than a rapid audit, with space to explain decisions and set out context.

The nominee role also contributed to a steadier process when filled by someone who knows the school well but is not essential to its day-to-day operations.

More professional dialogue, but higher expectation

That clarity in process, however, sat alongside a much higher level of expectation, which became clearer as the inspection unfolded.

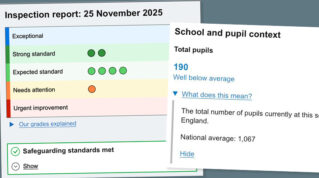

To meet the ‘expected standard’, schools must evidence every part of the criteria. The level required, from my initial experience, feels closer to the upper end of the old ‘good’ grade.

Trusts can draw additional capacity together at short notice to support this during an inspection, allowing the school team to focus on ensuring appropriate evidence is provided.

However, smaller or standalone schools may not have the same resources.

We also saw variation in how inspectors interpreted the criteria and the evidence needed to meet them.

We were grateful for the role of the senior inspectors (HMI) overseeing the inspection, who seemed to provide a sensible benchmark when interpreting criteria and assessing evidence.

National attainment averages carried considerable weight in discussions. Context was recognised, but only up to a point.

For schools serving lower-attaining or more deprived communities, the raised benchmark may be harder to meet unless judgment continues to evolve in line with the stated ambition of Ofsted’s chief inspector, Sir Martyn Oliver, that schools are assessed on what they can reasonably deliver.

Inspectors not interested in process alone

Our experience also highlighted several areas where schools will need to adjust their preparation. The first was around pupil groups. The pupil groups you flag early shape case sampling and follow-up lines of enquiry, so this needs careful thought.

Impact has also clearly become the central lens of this framework. Inspectors were not interested in process alone. They wanted to see what difference decisions had made and how consistently that difference was being felt.

The inspection data summary report was used to identify themes, and we were expected to explain individual data points. Inspectors wanted alignment between leadership narrative, documentation and what they observed.

Unsurprisingly, the scrutiny of inclusion also intensified. Inspectors compared classroom practice directly with special education needs and/or disabilities (SEND) support documents, education, health and care plans and provision maps.

Inspectors wanted to see that what was written on paper was being put into practice.

During our visit, we found it important to guide inspectors towards pupils whose needs were less visible, or the picture risked narrowing to those with more obvious adaptations.

This meant staff with inspectors during learning walks needed to know every class and every student with an adaptation to ensure appropriate adaptations were highlighted.

Welcome clarity, but intensity

Curriculum planning also came under scrutiny. Inspectors asked for medium-term planning, even though it was not requested beforehand. But we found that having this to hand showed coherence and avoided unnecessary pressure.

Ultimately, while it is still early days, the Ofsted framework seems to bring welcome clarity, but it also brings intensity.

Schools that once sat comfortably at ‘good’ may now find themselves working much harder to reach the ‘expected standard’.

That does not mean the framework is flawed. But it does mean leaders must adapt quickly and help our communities understand what has changed.

Thoughtful preparation and a clear, honest narrative will be essential to navigating a framework that sets a higher bar but gives schools the chance to show their best work when the call comes.

Your thoughts