Free schools have substantially fewer free school meals pupils and significantly more able children than other schools in their neighbourhoods.

Analysis of school census data for all free schools opened between 2011 and 2014 by Francis Green, Rebecca Allen and Andrew Jenkins from the Institute of Education (IoE) points to distinct differences in admissions between free schools – especially primaries – and other institutions.

The research, unveiled by Green at an institute seminar last week, is the latest of several reports to lead to allegations of social selection in England’s school system.

The Sutton Trust warned earlier this month that schools with the best Ofsted ratings were more likely to socially select pupils from higher-income families, after its report Caught Out found more than 1,500 primary schools had intakes not reflecting the socio-economic profile of their neighbourhoods.

The IoE research found that although free schools were more likely to open in more deprived neighbourhoods and more likely to take ethnic minority pupils, they were less likely to take those eligible for free school meals.

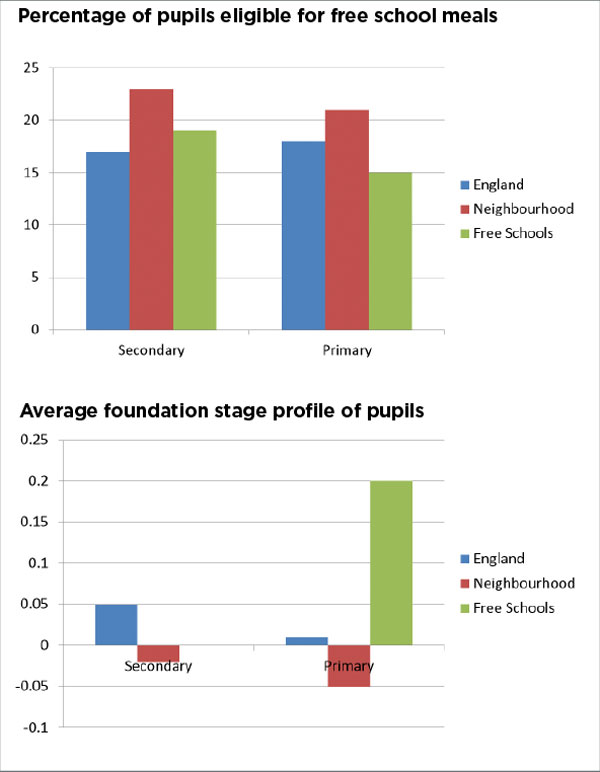

Of the year 1 pupils at free schools in 2011, 12 per cent were entitled to free school meals, compared with 19 per cent of that cohort across England and 24 per cent across the neighbourhoods in which the schools opened.

Overall, the proportion of pupils in years 1 to 3 at free schools who were entitled to free school meals was 15 per cent between 2011 and 2014, compared with 18 per cent nationally and 21 per cent in the schools’ neighbourhoods.

Pupils receiving free meals attract additional funding of about £1,000, a policy introduced partly to make them more attractive to school founders.

Nick Timothy, director of the pro-free school group the New Schools Network, claimed more recent data showed the gap had narrowed between the two groups.

“Most importantly, free schools are three times more likely to open in the most deprived areas than the least, precisely because these are the students that free school founders want to reach,” he said.

There was also a marked difference in ability, with pupils at free schools having an average foundation stage profile of 0.2 over the course of the study, compared with an average score in the schools’ neighbourhoods of -0.05 and a national average of 0.01.

Henry Stewart, from the Local Schools Network, said: “These figures are disturbing. They show free schools consistently have proportions of disadvantaged pupils that are below the neighbourhood average.

“We know that some free schools find ways to select a much more advantaged intake. This data suggests it could be more widespread than we thought.”

Janet Downs, also from the network, said free schools and other institutions that were their own admissions authority were able to socially select pupils using subtle changes to admissions criteria and other factors, such as more expensive uniforms.

The research did show that free schools take significantly higher proportions of ethnic minority pupils than the national mean. On average, 36 per cent of pupils at free schools were white, compared with 46 per cent in their neighbourhoods, and 72 per cent nationally. A large number of free schools are in major cities with relatively high numbers of young people from ethnic minorities.

It would be intetesting to know how intake profile changes with time. It is possible that this is symptomatic of a new school, rather than a free school.

A free school opened close to us in 2014. The site was confirmed after applications were made so the very first intake was from families who knew it was happening and could be flexible about travel.

Sibling effects might also impact recruitment as it is difficult to get children to two different schools, particularly at primary. Some children have subsequently moved, as older siblings reached the age to join the new secondary cohorts.

Where families have lived in an area for several generations, there may also be a preference to follow family tradition in going to a school that was attended by their parents or grandparents before. These children may also be attending alongside cousins or other relatives, which helps with logistics but is not recognised in the admissions process.

It will be interesting to see whether this effect persists as parents have a track record to inform choice.

It seems that no devious stone remains unturned in pursuit of distorting the evidence to prove that privatisation of our education system benefits children, families and society. Privatisation damages us all. And education without the Arts playing their full role is a very dangerous place to be in. We are creating the next generation of adults whose school life experience will have been that they were pawns in business’s games. They will know that their schools didn’t care about them as individuals, and they will be angry. We, as teachers, need to let them know that we care, and we need to stand up for our charges. If we don’t look after them, this government surely won’t.

Exploring the cultural bias that prevents pupils from lower income families benefiting from the advantage of opportunities that free schools and grammar schools offer. As previously mentioned a well trodden path based upon family history favouring a school may hinder a bright pupil from opportunities in selective education? Personally I support widening the market for education and empowering parents to make the best choice for their children.