Four in five university teacher training providers are questioning their future viability after changes have left them “unable to plan” their future.

A survey of 42 universities by the Universities Council for the Education of Teachers (UCET) shows the extent to which new recruitment rules have affected institutions.

Since September, higher education institutions (HEIs) have faced national “caps” on the number of trainees they can recruit in a bid to provide “moderate growth” in school-led training routes such as School Direct and SCITT.

In November universities were told to stop recruiting future PE, history and English teachers. The University of Cambridge said the caps would force its history PGCE to fold.

In response the National College for Teaching and Leadership (NTCL), which operates the caps, u-turned and allowed universities to recruit 75 per cent of the previous year’s numbers.

More than half of the HEIs providing initial teacher training responded to UCET’s survey.

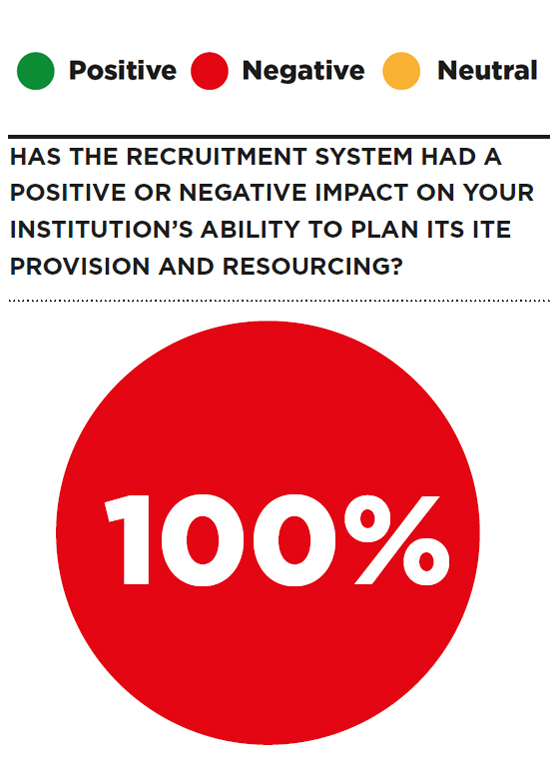

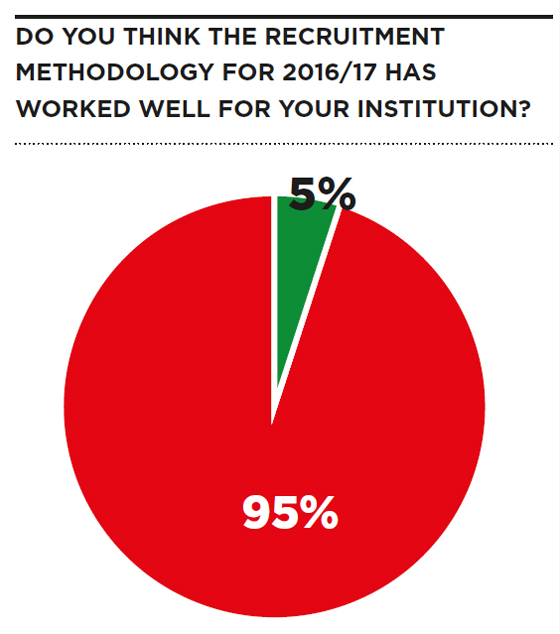

When asked how this new system had affected their ability to plan, all said it had an adverse impact and 95 per cent said they would not like to see the policies implemented again next year.

One said: “It has been a disastrous process from beginning to end. It started as an ill-thought out panic response to the fact the allocations methodology had become untenable, but the obvious flaws that were pointed out to NCTL by the sector were not addressed at the time.

“This meant the goalposts were shifted as the process got underway, and as a result, providers, school partners in School Direct and applicants have been left in a state of utter confusion.

“Candidates and schools are walking away from the process and giving up on initial teacher education. The teacher supply crisis caused by ministers, the Department for Education and NCTL will continue to deepen.”

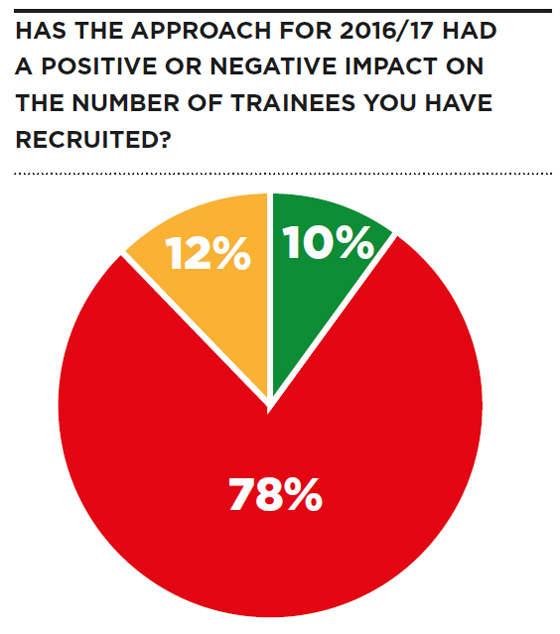

Seventy-nine per cent of respondents said the changes affected the viability of their courses, with many highlighting staffing concerns amid the “uncertainty” of the policy.

Without knowing student numbers in advance it was difficult to budget for an appropriate number of staff. Each student brings in £9,000 to the university.

James Noble-Rogers, UCET’s executive director, called for the government to re-evaluate recruitment.

“It is clear that the current recruitment system does not work. It is damaging the teacher supply base, undermining high quality training programmes and harming children’s education.

“The government must, as a matter of urgency, introduce a sustainable system of recruitment that allows initial teacher education providers to plan over a number of years.

“It must also develop a more sophisticated model of teacher education that is genuinely focused on the needs of schools, and not based on outdated stereotypical assumptions about what university involvement in teacher education actually entails.”

Respondents to the survey were not unanimous about the best way to recruit the next cohort of teachers, who will begin training in September 2017.

A quarter wanted “open and sustained recruitment”, while just under a third thought recruitment controls for priority subjects and institutional allocations for others would be best.

The largest group (45 per cent) wanted a return to the allocations scheme, where universities were informed in advance of their allocated maximum numbers.

Last week, in a hearing held by the public accounts committee, MPs told the NCTL of their concerns about the changes. Conservative MP Stephen Phillips asked if the government was going to “relook” at the policy, saying it seemed to have a toxic consequence on training.

NCTL’s director of programme delivery, Sinead O’Sullivan, said: “The issue with the past few years is that we have been growing School Direct, and that has created more volatility in the system.

“We have unfortunately been learning as we go, just as the providers have. I would like to be able to give longer-term commitments to providers in the future, and we are certainly looking at whether we can do that.”

According to the latest recruitment levels, higher education institutions have reached, or almost reached, their cap in more subjects than other routes. The salaried School Direct route still has 16 subjects with 50 per cent of places unfilled. The tuition fee route has 13 subjects unfilled; HEIs have 12.

What the universities say

“The pace of recruitment nationally in some subjects and primary has meant more local recruitment patterns have been overlooked. It has also meant that applicants and providers enter a race in which rapid decisions take precedence over more informed ones.”

“We are very concerned that the lack of allocations methodology leaves us vulnerable in a fixed market economy, where speed is of the essence and potentially impacts on levels of quality in recruitment. That, coupled with the uncertainty of overall numbers, makes it very difficult to plan strategically for the development of ITE, where instead we are looking to consolidate, rather than champion change.”

“We have radically overhauled our recruitment procedures . . . including interviewing every fortnight rather than every month as in previous years. This has had a positive impact on global numbers, but has taken twice the staffing hours.”

“For a small provider the impact of fewer applications is devastating. The nature of the subject profile we need to support is changing, meaning a reliance on part time hourly paid staff, which we are recruiting at the last minute.”

“The need to recruit students early has meant that some good quality applicants who applied later have been excluded.”

Your thoughts