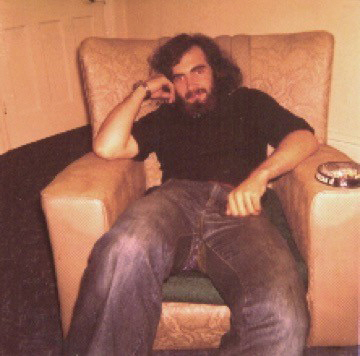

Dylan Wiliam looks like a cross between a wizard and a rockstar: domed head, greying beard, twinkling eyes and a mischievous smile that suggests he knows the secrets of the universe.

But it isn’t just me who is captivated watching the end of his teacher training session in a bland east London hotel. The maths teachers sitting in front of him are fascinated, too.

Known chiefly among the teaching community for introducing “assessment for learning”, a near universally-used set of methods for giving pupils feedback, Wiliam is one of only a few modern education theorists to become a familiar staffroom name. In fact, he is dangerously close to being a public intellectual. When he tweets, teachers pay attention. When he turns up to events, people flock to hear him. The wizard-rockstar analogy goes further than his looks.

Yet, as we sit down to chat over an empty lunch table – he rarely eats when leading seminars – Wiliam reveals that his current image is far from the one he had of himself as a child.

Raised in Cardiff, and son of an Oxford-educated professor, Wiliam was a clutz. “I was very badly co-ordinated and couldn’t write legibly. I still print, basically.

“I was always the last kid to be chosen – “Oh, no! We’ve got Dylan! – and so I have a vision of myself that was formed from that experience.”

It was not until he was 14 when a geography teacher who ran a weight-training club at lunch-time, took Wiliam under his wing – and changed his life.

“I did an hour of weight training every day for three years and I kind of emerged, almost like a chrysalis . . . I became captain of the rugby team, house captain in athletics, it was really strange, this transformation from being completely useless at sports to being a kind of ‘jock’.”

This would not be the only time Wiliam had to transition from being the underdog. To his father’s disappointment neither Oxford nor Cambridge invited him to interview. Though he got a place at Durham, he graduated with “only a general degree, and a third at that”.

He was relieved to pass at all. “I don’t know if I was depressed at university or not, but there are large areas where there is a sort of haze about what actually happened.”

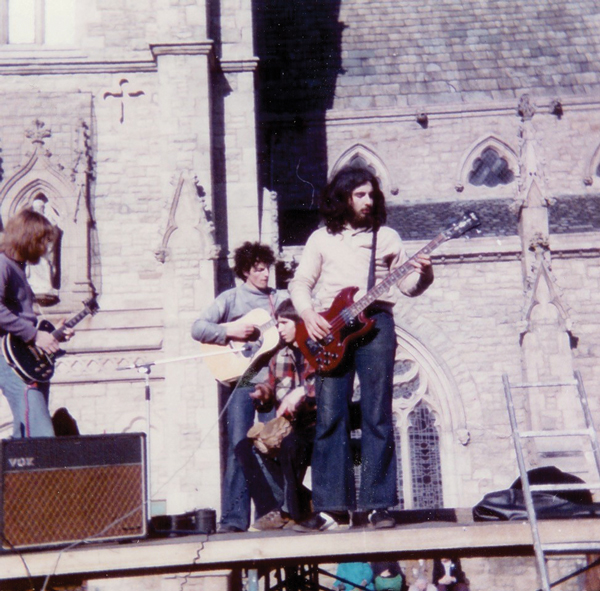

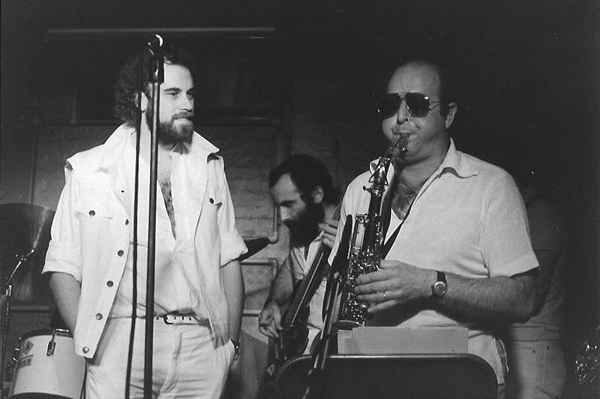

Much of his focus was on music, rather than studying. He played in a band called Lynx, whose preferred genre was “jazz-folk”, though their influences were eclectic. He paid little attention to his degree classification as he felt it would matter little to someone who was going to be a professional musician

But his plans ran into a problem when, after he finished university, his father announced that he would be taking up a position at the University of Connecticut, and Wiliam could not remain in the family home.

Wanting to follow the band to London, Wiliam applied to do a PGCE at Goldsmiths, but didn’t hear back. Increasingly desperate he went to an employment agency that specialised in appointing teachers to private schools.

“For a long time I had this imposter syndrome”

“I said, ‘I need to get a job’, and they said, ‘We’ve got this private crammer in Worcestershire’ and I said ‘OK, that sounds great’.”

For a year he taught the sons of famous businessmen and earned less than the pupils received for pocket money.

“It was a very easy job and after a year I thought that if I’m any good at this I shouldn’t be doing it in the private system, I should go and teach in the state sector.” Which is what he did.

Working first in west London he continued practising with his band three evenings a week, but realised after a few years that he could not do both.

“To my horror,” he gurns, “I discovered I was enjoying the teaching more than the band!”

Wiliam laughs. This truth clearly still amuses him, but the joy he gets from learning is evident time and again.

Having taught maths for seven years, his shift to academia came out of sheer stubbornness. Turned down for an internal promotion, he took a research fellowship that he was offered the next day.

“I guess it was just the temptation of saying Sod you! . . . plus I think it simply too good an opportunity to miss.

“Everybody thought I was crazy giving up a permanent job as a maths teacher for a one-year fellowship – but I didn’t think it was crazy at all!”

Two years later, he applied to become a permanent lecturer at King’s College London, but thought he had so little chance that he dropped all the documents he was carrying when he found he’d got the job.

Was that a sign of the awkward teenager still inside him? Perhaps, he says.

“Certainly for a long time in my career I had this imposter syndrome thing of ‘They will find out there has been a mistake and I will have to go back to teaching in Shepherd’s Bush’.”

Imagining Wiliam feeling unconfident is difficult when you see teachers watching him with adulation. I ask what he thinks has contributed to his being so well-regarded, given that he never actually trained as a teacher nor came from a secure academic background?

“I have reflected slightly on that,” he says, “I have a very good memory, so academia is clearly a good place for me. I think I have fun . . .

“It’s never occurred to me to do anything because somebody else might prefer me to do it in a particular way, and that could well be the secret to getting promoted in some kinds of organisations.”

He also says he has been lucky. He is more than aware that great people around him have helped, and that there have been times when he floundered without them.

He also credits his wife with a great deal. Siobhan is mentioned time and again. They met, as all romantic tales begin, at a maths teacher conference. While he did an Open University maths degree to bolster his weak knowledge, his wife did a masters and both would work, every night, cracking the books. As each progressed in their career they have supported one another.

When he moved to the US to work at an education testing service, she took a job there and was promoted three times.

“She’s far smarter than me. One of the senior research directors there described her as scary smart.”

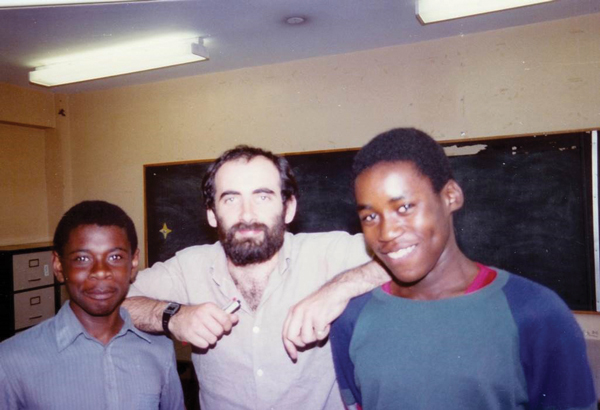

The pair also fostered teenagers for 15 years. “At the time, because Hackney had a ban on transracial fostering and adoption, they invested very heavily in recruiting black foster parents and so, for a while, we were the only people fostering white kids in Hackney, so we had five at one time.”

These days Wiliam and his wife split their time between the US, the UK, Australia and the Far East.

“The model we have been developing for teacher learning communities has now been adopted by South Australia, and two thirds of the primary schools in Singapore. The work is also taking off in Sweden so I’m going there next week . . . but I do need to cut down on the travel because it’s a bit crazy.”

For now, however, our no-lunch hour is coming to an end and teachers are re-entering the hotel’s lecture suite. Wiliam zips back to the front of the room, moving papers, arranging slides, getting ready to perform, his energy evident as ever. The teachers, sliding into their seats, are already silent and waiting for the magic to begin.

IT’S A PERSONAL THING

If you could only take one book to a desert island, what would it be?

John Tukey’s Exploratory Data Analysis. It’s more like a disorganised antique shop than a book, and I’m always finding new things in there whenever I revisit.

What three things would you save from a fire?

The first thing would be my partner, Siobhan. But if you mean inanimate objects, then my passport, my green card, and my laptop…

What do you have for breakfast?

Typically a mushroom and cheese omelette.

What is the best concert you’ve ever attended?

Gary Boyle’s Isotope. I never much liked their recorded music, but the concert they played in Durham in the mid-1970s was amazing.

If you could revisit one period in history, when would you choose?

I’m pretty sure I would rather be in the here and now rather than anywhere else, but if I couldn’t, then the US in the 1950s.

What was your favourite childhood toy?

My Meccano set.

Your thoughts