Ofsted’s use of the national average when grading schools on achievement could be “extremely unfair” to those serving disadvantaged communities, leaders have warned.

The watchdog has made inclusion a key focus of its reformed inspections. But leaders say the framework could penalise schools with high levels of poverty, special educational needs and disabilities (SEND) or large numbers of children who speak English as an additional language.

The inspectorate stressed that inspectors consider a school’s context, using both data and information gathered on site to “form a holistic view of achievement”. But to reach the ‘expected standard’, inspectors must be satisfied that “on the whole, pupils achieve well”.

“Typically, this will be reflected in their attainment and progress in national tests and examinations, which are broadly in line with national averages, including for disadvantaged pupils,” the grading toolkit said.

NAHT general secretary Paul Whiteman said the union was “very concerned” this could “unfairly mark down” schools with larger proportions of disadvantaged pupils, or those with SEND.

“These pupils may have low prior attainment, but nevertheless make considerable progress,” he said.

Averages also factor into grading decisions for ‘attendance and behaviour’, where to meet the expected standard, overall attendance must be “broadly in line with national averages or shows an improving trend over time”.

Andy Jordan, inspection and accountability specialist at leaders’ union ASCL, said Ofsted’s secure fit model and use of averages risk making it harder for schools in more deprived areas to attain middle or top grades.

He said the new model appears to be “unfairly judging schools for issues that go beyond the front gates” and called for Ofsted to “reconsider their methodology and ensure they avoid penalising schools that are doing good work in tough circumstances”.

What does the data show?

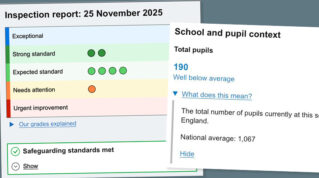

Schools Week analysis of the first 62 routine, non-voluntary inspections under the new system shows around one in three received ‘needs attention’ for achievement – more than any other evaluation area.

The 20 schools appear to be split across deprivation levels. Nine were “above” or “well above” average, four “close”, and seven “below” or “well below”.

The split was similar for free school meal eligibility, with five “close”, eight “above” or “well above”, and seven “below” or “well below”.

But the sample is still small, and leaders remain concerned.

Lack of ‘wriggle room’

Richard Sheriff, CEO of Red Kite Learning Trust, has been through two inspections under the new framework. He fears a school’s context “is not influencing any of the grade” and the approach “feels extremely unfair”.

One Red Kite school in Leeds was judged ‘needs attention’ for achievement.

Inspectors acknowledged that many pupils joined part-way through schooling and the school supported them to catch up. But pupils “achieve less well than could be expected” in tests and exams.

Sheriff said the local area has “generations of … compound disadvantage and school non-attendance”.

“Last year just over 21 families lost a parent … It’s just profoundly different.

“How on earth can you use a national average against a population that’s clearly in no way average? It’s just statistic nonsense.”

He warned that schools in similar areas risk slipping automatically into ‘needs attention’, while staff “serving in these schools brilliantly are being underserved by a draconian and basically out-of-touch inspection.”

Context must be reflected

Two E-ACT schools are also among those rated ‘needs attention’ for achievement – E-ACT Nechells Academy, a primary in Birmingham, and City Heights E-ACT Academy in Tulse Hill, south London.

Both sit in areas of “well above average” deprivation.

At City Heights, 24 per cent of pupils receive SEN support, almost 6 per cent have an EHCP, and 61 per cent are eligible for free school meals (FSM).

At Nechells, SEN support is above average at (18 per cent), while FSM is 71 per cent.

CEO Tom Campbell said he welcomed Ofsted’s focus on attainment and progress, “but national averages don’t always reflect the context of many of our academies”.

“Schools with high proportions of disadvantaged pupils, pupils with SEND, or high mobility can see headline figures affected by factors beyond the control of teaching and leadership,” he said.

He pointed to Nechells, which was praised by inspectors for improving outcomes for disadvantaged pupils, and phonics and multiplication. But several pupils joined in year 5, leaving too little time to “get them fully up to speed” for SATs.

“As a result, the school was graded ‘needs attention’ for achievement.”

Campbell said he hoped this “teething issue” can be “ironed out, so judgments can fully reflect both attainment and progress in context.”

Oliver: Inspectors are looking at context

One audience member raised similar concerns to Ofsted chief inspector Sir Martyn Oliver, during a Q&A at BETT UK last month.

“We work within deprivation, and people come to us with very low reading ages,” he said. “The work we do with them is extraordinary, and the progress that they make is excellent”. Yet the school is “judged against” other schools including local grammars.

Oliver responded that he was “watching very carefully” but “can already see that there are schools with low achievement getting beyond ‘expected’, ‘strong’ and ‘exceptional’ grades”.

“I can tell that my inspectors are taking the context into account,” he said.

He said removal of headline grades means the system can show weakness in achievement while recognising excellence elsewhere.

But Wolverhampton headteacher Philip Salisbury fears many parents will still judge schools closely on achievement and warned the system risks “setting schools up to be either … inclusive or academic”.

He also worries that schools could be deterred from admitting pupils who could dent results.

Salisbury leads a primary where more than 55 per cent of pupils are eligible for free school meals. Around 80 per cent speak English as an additional language.

“If you are comparing across national averages, a school like us is always going to struggle,” he said.

“Achievement becomes the weakest-looking area, even when the provision could be strong.”

Education consultant Steve Wren said he also has “significant concerns” that the achievement toolkit “is biased against” schools working within more difficult contexts.

“It is self-evidently more challenging for schools with low prior attainment to have exam outcomes in line with national averages.”

Inclusion tsar welcomes raising outcomes

But not all leaders have been critical. Wodensborough Ormiston Academy, whose trust is led by government inclusion tsar Tom Rees, has also been rated ‘needs attention’ for achievement, while achieving ‘expected standard’ in all other areas.

Disadvantage and SEND levels at the secondary are “well above average”.

Its report stated pupils’ outcomes in exams at the end of KS4 “remain below the national average”.

Work to improve this, including for pupils facing barriers to learning, “is beginning to show some positive improvements”, but “too many pupils still do not achieve as well as they should”.

Rees said: “We are proud of the improvement at Wodensborough in recent years.

“We welcome the greater emphasis this new inspection framework places on inclusion, alongside a continued focus on raising outcomes.”

Averages ‘just one part of picture’

An Ofsted spokesperson said: “Pupil achievement is at the heart of our report card because outcomes matter.

“It is vital that every child is provided with the tools they need to thrive, no matter their local context. To be truly inclusive means setting high standards for all children.”

Performance in national tests and exams, and how this compares to national averages in the IDSR, “is just one part of the rich picture of achievement in a school”, they added.

“Inspectors use a range of data, including national averages for disadvantaged pupils, to understand achievement better. In forming grading decisions, they discuss each school’s context in detail with school leaders.”

Some leaders have suggested that the use of averages means half of schools would not be able to meet the expected standard. But Ofsted has said that won’t be the case.

For each achievement measure, schools are placed in one of three bandings depending on where they sit on a national distribution range. Performance near the average range is banded “close to average”, while others will be “above” or “below”.

Ofsted said inspectors “never look at a single measure for a single year in isolation”, and instead look at data over multiple years and measures to “identify consistent and comprehensive patterns” and smooth out year-on-year variations.

This issue also runs through attendance and EYFS. As a principal of a 2-16 academy we had a limited judgement in EYFS at expected standard due to strong bullet point 5. Essentially students must be generally be above GLD – this is ludicrous as we serve on of the most deprived communities in the country and children join us way below expected at 2 years old. Attendance is also an issue – no disadvantaged serving school is likely to get strength. Achievement was the only needs attention for us due ks2 data – again disadvantaging both schools in challenging circumstances but also 2-16 schools. 95 % of our students do their whole education with us and achieve well at ks4. It seems mad to measure us halfway on that journey and find fault – primaries are not measured on ks1 data – nor are secondaries measured on Y9.

There is an assumption here that school achievement gradings are based on national averages for raw attainment. This is wrong. Far fewer than 50% of schools have attainment statistically higher than the national average. This is because schools are banded not ranked against the national benchmarks and statistical tests measure if any differences from national averages are meaningful. Achievement in public exams is based on attainment and progress. Progress measures compare students against others nationally with similar starting points. Below average attainment but close to average progress may not be a concern, especially if students on entry have low starting points. Persistent statistically below average progress is a concern. Single year dips or spikes in achievement data are cautiously handled in favour of looking at 3-year trends. Achievement over time is more important than achievement at one point in time. Leaders who have a firm understanding of what the data does and doesn’t say about their schools are in a better position to explain the school’s context with confidence and link this to achievement.