In the week following the EU referendum, much discussion has centred around the educational background of the “inners and outers” and whether it affected the poll’s result.

Schools Week decided to see if there was a relationship between a local population’s education and referendum outcome.

Voters in areas with higher-performing schools were less likely to have voted to leave the European Union (EU) last Thursday.

Schools Week dissected various data sets against the proportion of votes to leave the EU to determine if there was a relationship between a number of factors – including educational attainment.

We found local authorities with better GCSE results (based on the proportion achieving five A*-C grades, including English and maths) had a stronger Remain vote than areas where educational outcomes were not as high.

Our investigation also revealed that areas with a greater proportion of pupils classed as having English as an additional language (EAL) were less likely to have voted to leave the EU.

Local authorities with more pupils in full-time post-16 education were also less likely to have voted to leave.

But we found the level of deprivation in an area was not an indicator of how people voted.

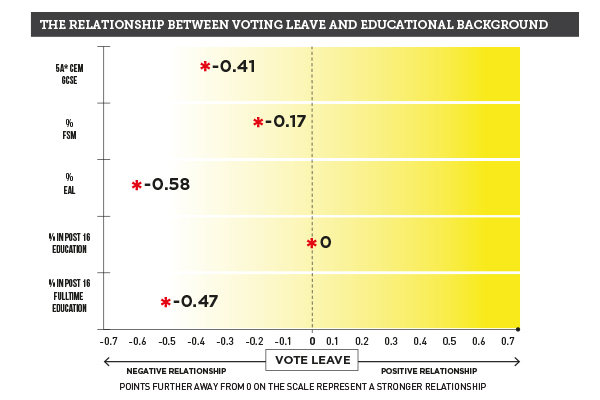

Dr Meenakshi Parameshwaran, from Education Datalab, explained that relationships of 0.7 or more (positive or negative) are considered to be the strongest.

Dr Parameshwaran, who last year discovered that areas with the highest proportion of Ukip voters were from regions with more underperforming schools, said our findings were not conclusive, as the scores fell under the 0.7 barrier, but showed education did have some impact on the way people voted.

“Ukip is quite clearly connected to disadvantage.

“But with the Brexit vote there are some affluent areas with good school performance that voted to leave so you have a more confusing story; you have affluent Tory areas voting to leave, so the patterns aren’t as clear.

“That’s why the correlation isn’t huge. It’s a muddled story.”

Our analysis found a moderate, negative correlation (-0.41) between GCSE results by local authority and Leave votes – which means that areas in which schools post better exam results were more likely to have voted Remain. Of the local authorities that voted to remain, 92 per cent had above average GCSE results (see graph, above).

Immigration was a key battleground in the run-up to the referendum, but national figures show areas with higher levels of net migration actually had higher proportions of votes to remain.

And Schools Week found that areas with more EAL pupils also had fewer votes to leave the EU. It was the strongest relationships (-0.6) between factors and voting in our analysis, although this is strongly influenced by London – where immigration rates are at the highest and which had one of the strongest Remain votes in the country.

When London is taken out of the picture, the correlation between EAL pupils and voting almost disappeared.

Boston, in Lincolnshire, had the highest proportion of votes to leave the EU (75.6 per cent). But just 8.4 per cent of pupils in Lincolnshire are classed as EAL, less than half the national average.

National media have widely reported that degree holders were more likely to have voted to remain in the EU.

Our analysis found post-16 education showed some relationship with votes to leave or remain.

Areas in which more pupils were in full-time education after their GCSEs, rather than any form of further education, had a weak correlation with votes to leave the EU (-0.47). If all post-16 provision was taken into consideration, there was no correlation at all with the way an area voted.

The proportion of disadvantaged pupils in an area showed almost no relationship to a vote to remain or leave; a negative correlation of -0.16 was found between disadvantage and a vote to leave.

Loic Menzies, of think tank LKMco, said it was not for schools to “decide which way they want to push people to vote”.

But he added: “What this really shows is that when there are big decisions like this . . . young people need to be equipped with the skills to deliberate and question the evidence that is being put forward to them, and make the right decision on their own values set and belief.

“That raises questions about how we teach citizenship and how we create schools that promote young people’s ability to look at big questions in a critical way.”

The correlation between proportion of EAL pupils and voting for Brexit depends more on hyper-local conditions than area-wide ones. Lincolnshire as a whole may have a far lower proportion of EAL pupils than the national figure, but some Boston schools have more than twice the national proportion. For example, three Boston primaries have a proportion many times larger: Park Academy (54.2%), Carlton Road (59.4%) and Staniland Academy (49.7%).

Apparently we’re not meant to listen to experts anymore, according to one ex-Secretary of State for Education, so your research is clearly invalid. Relying solely on gut instinct, the lies of Michael Gove and a hatred of foreigners, I’d say it woz the Sun and the Mail wot won it.

Gove seems to have changed his mind about the ‘Nazi’ experts. He’s changed his mind about one of them, Mark Carney, who he had accused of being in the pay of the Government. Carney now gets the full force of Gove’s praise. http://www.localschoolsnetwork.org.uk/2016/07/from-nazi-to-saviour-in-a-couple-of-weeks-the-flip-flopping-of-michael-gove

“That raises questions about how we teach citizenship and how we create schools that promote young people’s ability to look at big questions in a critical way.”

Would we get the same sort of analysis after a General Election?

The underlying narrative seems to be that those who voted to leave the EU are “thick” or if we gave people more education they would vote for remain in the EU. Those that voted for remain in the EU seem to be searching for some rationale to explain why citizens had a different view to them.

Lots of factors were at play in the referendum. Each person voted by weighing up the evidence as they saw it. Just like in a General Election except in this case, more people were moved to vote.

There has been the same sort of analysis. See YouGov after the 2015 election:

https://yougov.co.uk/news/2015/06/08/general-election-2015-how-britain-really-voted/

There have been many generalised smears after the Referendum Vote. But like all generalisations, they’re not true. All those who voted leave are ‘thick’, not true. They’re so poor they’ve nothing to lose, not true. They’re all racist, not true. Those who voted to remain are all metropolitan types fearful of losing their cheap EU nannies, not true. They are oldies who’ve shafted the young, not true. They want to smear those who voted to leave as ‘thick’, not true.