Clive Webster has vivid memories of the day Muhammad Ali visited his family home in Harlesden, a north-west London neighbourhood that he describes as “Afro-Caribbean-Gaelic”, sometime in the mid-1970s.

He drops this into the conversation when I ask him the three people – dead or alive – he’d invite to dinner.

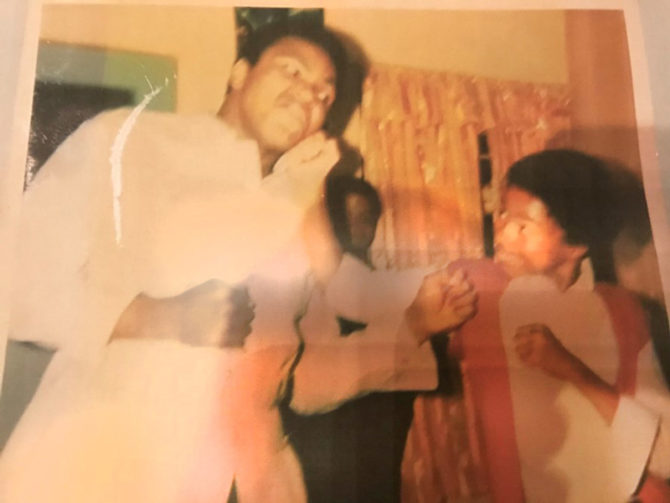

Ali would be there, he says, with two of the literary icons of the 20th century: Philip Larkin and Linton Kwesi Johnson. But wouldn’t Ali feel out of place in the company of three poets (Webster published an anthology when he was younger)? “He’s actually been in my dining room,” he replies. “He’s stood in our hallway on our Bakelite black telephone and taken the poetic mickey out of my sister’s boyfriend.” Webster was 8 or 9.

People are a little bit tired of the race debate

We’re ensconced with tea and biscuits in an old country house just outside Maidstone now leased as office space to organisations such as the Kent Catholic Schools Partnership, which Webster heads.

Back to Ali. The heavyweight champion was in Wembley sorting out a fight. Webster’s oldest sister (he’s one of six) was hanging out with her boyfriend, who knew one of Ali’s entourage. The boxer was intrigued by the stories of her family and decided he wanted to meet them.

“He got on the phone, spoke to my mother, suggested that she put us all in a taxi and take us to Wembley. My mother, being the diminutive but very determined lady that she was, said ‘You must be joking, if you need to see us, you’ll have to come down to us.’ ”

Webster’s dad was on a carpentry job in Brighton, but his sister sprinted around the neighbourhood corralling the family. One brother, Philip, was at the youth club with his best friend, a kid called Cyrille Regis and a keen footballer like himself. In the family photo of Ali striking a fighting pose in the hallway with Philip, Regis – who would go on to play for West Bromwich Albion and England – is peeking out from behind the boxer.

Webster’s mother was from Galway and his father migrated from Guyana as part of the Windrush generation. “Being a mixed couple in the 1950s and 60s, they lived through going to find rented accommodation and seeing the posters that said ‘No Blacks, No Irish, No dogs’. My mother used to joke to my dad: ‘Thank goodness, Bertie, you haven’t got a dog!’”

He cites his parents’ strong work ethic and high expectations as a huge driving force in the lives of all their children. His older brother was “the first from that whole community to even aspire to go to university – and to go there”.

After his own undergraduate degree, Webster was accepted on to a four-year course to become an educational psychologist, which involved a PGCE year, two years of teaching and a year at the University of Southampton.

He then zipped off to southern Spain to teach English for two years (he thought learning another language was important) before returning to the south of England to work his way up through various local authorities. By 1996 he was the country’s youngest principal educational psychologist, in the London borough of Hillingdon.

After five years in senior posts at Surrey, he applied for the newly created role of director of children’s services, in Southampton. “Post-Climbie and Baby P, the drive was to bring education and social care together under one umbrella. All local authorities were appointing their first directors of children’s services as opposed to directors of education.

“Given my background and experience and dare I say it, by then, expertise, I was successful in becoming the first director for Southampton, almost certainly the youngest, and definitely the only black director of children’s services at that time.”

He stayed for seven years, through a “very turbulent time” at the peak of austerity. “I became quite uncomfortable because you don’t go to work to make redundancies. . . what you really get out of bed for is to protect children and make a difference to their educational outcomes.”

As he talks about his new role in multi-academy trust leadership and “the idea of spearheading an organisation that is solely focused on turning some of the rhetoric of giving children the best chance in life into a reality”, you wonder how many good people were lost from local authorities all over the country as a result.

Webster was the founding chief executive of the Kent Catholic Schools Trust five years ago, mandated “to turn it from an aspiration into a reality”. The aspiration was to bring all 32 of Kent’s Catholic schools under one umbrella. To date, five secondaries and 19 primaries are on board, with eight schools “yet to be persuaded”.

Webster has always made sure he’s “supremely well qualified. I’ve also taken bold steps to acquire the experience I need . . . I’m in no doubt I’m in this role fundamentally on merit, which is very important.”

We’re talking about diversity and, more specifically, black representation in education leadership, which is why Webster approached me. He’d been at the Ofsted annual report launch in December, and been disappointed by the whiteness not only of the panel, but also the audience. This is purely anecdotal, of course – a more objective measure is the proportion of black and minority ethnic headteachers in England (3 per cent, although 8 per cent of teachers are black).

“The fact that it’s still very unusual to see a black headteacher or a black chief executive or a black director of children’s services is sad and significant,” Webster says.

“We haven’t made progress at a number of levels. If we were getting things right further down the line, we should be seeing far more black representation coming through the middle and senior leadership of all manner of public services.”

He finds the current trend for a broad focus on diversity somewhat unhelpful. “There’s a sense in which the black element of black and minority achievement is being lost under what might seem a more palatable heading of diversity – which are issues that are really fundamental to how we operate as a cohesive society. But the extent to which it is still about how well black children are doing, or the extent to which you see black professionals, is lost.”

So how many black and minority ethnic heads does he have in his trust?

“We don’t! Leadership positions come up every so often. You’re always having to work incrementally, you can’t run roughshod over the entitlement of everyone to every position. You can’t positively discriminate in a way that would be unfair to others.”

Mentoring, coaching, and role-modelling are “still very much remedial responses”, he says, and recruitment strategies a “tactical operational response to a deep-seated issue that we’re all grappling with”.

So how can the more deep-seated issues, which can lead to racist abuse, discrimination, or a lack of aspiration, be addressed?

I’m in no doubt I’m in this role fundamentally on merit

“We’re at a very important juncture in terms of race in this country. It’s far more about having a race resolution than just a race debate. People are a little bit tired of the race debate.”

Speaking out is one step. The next, he concedes, would be to look more closely at how his own trust could address the issues of creating aspiration in young black men and women, which is “a debate we’re yet to have”.

“It would be remiss of me in the relatively privileged position I’ve got, not to use that to say I and many others need to do far more, so that if you fast-forward 30 years we are not having another version of this debate.”

CV

2013 –present CEO, Kent Catholic Schools’ Partnership

2005 – 2013 Director of children’s services, Southampton City Council

2000 – 05 Assistant director for children and young people then assistant chief executive, Surrey County Council

1999 MBA, Kingston University

1996 – 2000 Principal educational psychologist, London borough of Hillingdon

1993 – 96 Senior educational psychologist, London borough of Wandsworth

1991 – 93 Educational psychologist, Essex County Council

1989 – 91 ESL teacher and head of English, The English Centre, Cadiz, Spain

1989 Masters in educational psychology, University of Southampton

1986 – 88 Teacher and SENCo, Sutherland Middle School (now Sinclair Primary), Hampshire County Council

1986 PGCE, La Sainte Union, Southampton

1985 2:1 Joint honours in philosophy and psychology, University College, Cardiff

1967 – 80 St Joseph’s Catholic Primary and Cardinal Hinsley Catholic Secondary (now Cardinal Newman Academy), Harlesden, north-west London

Your thoughts