It is raining heavily outside Abacus Belsize Primary, a chalet-like wooden structure hidden among a series of houses accessible via an almost invisible path near London’s grand King’s Cross Station.

It’s early enough in the school year that parents are still hovering in the entrance, partly to avoid the wet, partly to watch their little one traipse into a nearby classroom, and there’s a sense of friendly community as wellies are unwedged and raincoats hung on tiny pegs.

When Chris Tweedale, chief executive of CfBT Schools Trust, appears he has the headteacher, Vicki Briody, by his side. Clearly proud of their achievements — the school was one of the first free schools to be rated as outstanding — both want to show me around the former canoe education centre rebuilt to house their pupils.

In one room children are greeting each other in Mandarin, in another they are playing in a sandbox. We travel across a wooden bridge over a colourful playground. The rain splashes away in the canal that runs beside the building. Even in the storm it feels a happy place.

Tweedale’s gentle manner likely has an influence although he is the first to praise the headteacher and her staff: “They’ve done an incredible job here, really.”

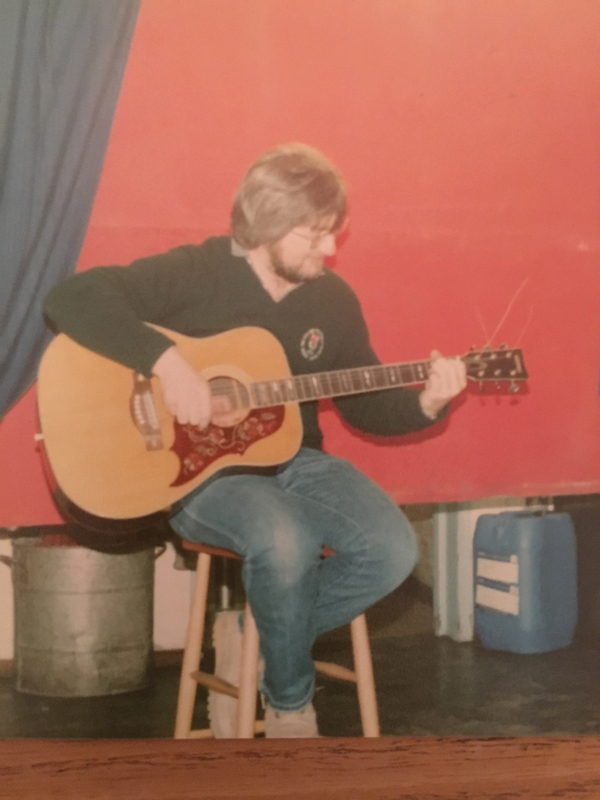

His breadth of experience also should give confidence to the staff. He was first a teacher, travelling up the promotional leader to become a head, before working on national government policies at the Department for Education. There’s also an unusual mix of steeliness and warmth in his manner, almost as if Mary Poppins had an older brother who speaks with a Rochdale accent.

“Teacher training? It meant I could stay and play rugby”

Starting his teacher training in 1978, he began “for all the right reasons … it was a good department and it meant I could stay and play rugby!”

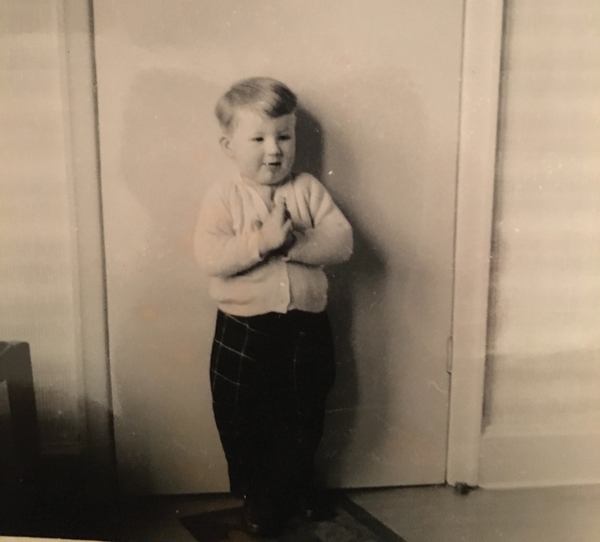

It was also, perhaps, because he had always enjoyed school.

“I loved it, I had a fantastic time and had great teachers — and some of those teachers enthused me into wanting to get involved in education. My mum was the headteacher’s secretary, this was Bishop Henshaw Memorial High School, a Catholic comprehensive in Rochdale, a 14-18 school.”

In top sets for everything, as well as being sporty and musical, he admits to having one weakness.

“I wasn’t very good at languages. I had a teacher who called me ‘the petit criminale’ or ‘Timmy Tweedale’ all the way through. Two years! You just wouldn’t get it now. Deliberately, he used to pick on me. Anyway, I managed to pass at O-level but heaven knows how.”

His northern accent is still discernible, despite the 58-year-old leaving home more than 40 years ago. It is a family trademark, he says, beginning a story about his father’s work selling textile machines.

“He went to East Germany at one point… I was about six or seven and my brother was just born and he was supposed to go for a fortnight. But he was guiding this thing down on pulleys and the chain broke and the whole lot fell on his leg. He was in hospital in East Germany for nine months.

“He came back with no German at all — instead he taught the doctors and nurses English. A few years later, when I was about 14, one of the doctors who had done the operation on his leg got permission to come to a conference at Manchester University, and he came to our house for dinner.

“I was quite excited to meet him, so I opened the door, and this East German doctor just looked at me and, in a perfect Rochdale accent, said, “Oh, ‘ello Christopher. I’ve heard a lot about you!” I’m sure there’s this little town in East Germany where they all speak like they come from Rochdale.”

His first sojourn from the north was to the University of Leicester, where he studied geology, but decided it wasn’t a ripe subject for a career after the oil market went into decline and the only jobs left involved “being a mudlogger in the North Sea or living in a tent in Australia — and neither of those really appealed”.

Chortling, he explains how he wanted to withdraw midway through his first teaching job interview, at a school on the Isle of Wight. But it would mean that he’d lose his right to expenses, including the ferry fare and hotel. With relief, he just missed out. His next interview was with Angus MacMillan, then-headteacher of Cardinal Wiseman in Ealing, west London. Again, Tweedale was unsure, but this time MacMillan saw his potential and took him on a walk around the grounds to convince him.

Tweedale credits MacMillan with him wanting to become a head. “Right from me being a newly qualified teacher he was telling me to think about being a pastoral lead, then a head of department, then probably head of sixth form, and to learn to timetable… it seemed such a natural thing to do.”

Years of preparation and gradual promotion didn’t stop his eventual rise to headship at John Masefield High School in Herefordshire from being a challenge.

“I was so nervous I could barely speak at the first staff meeting.

“When you’re a deputy people listen to your opinion but they always know the one that actually counts is the head.

“And people look at everything you do — they look at your body language . . . not just at what you say but how you say it.”

It was only later, when he became a policy adviser at the Department for Education, that he says he really understood what power the role had. “When I went there I had no power, I was either there to be listened to, or not. But I had the ability to influence people and I did find that stimulating and really exciting.”

During his time as head, Tweedale challenged what he saw as the sort of practice now described as “coasting”. Later, in his advisory government role, he oversaw the introduction of school improvement partners — a policy under which every school had a partner working with leaders to support its improvement — and notes it is as his proudest achievement from his time there.

It’s an achievement that reflects his past mentoring from MacMillan. But it’s also apparent in his work now at CfBT Schools Trust, an academy chain that oversees 19 primary and secondary schools, including Abacus Belsize.

Being the leader of an academy chain is still a relatively new job, one that Tweedale says the sector is “being made up as we go along”. But he means it optimistically; the ability to shape the job is bringing innovation to the role.

“It’s very operational, very immediate, it’s more like being back at school … there’s also a definite strategic skill about what you want the trust to be like.”

On the basis of Abacus Belsize, it would be easy to think that what he wants is a happy, friendly school where learning is happening in every corner. But the real answer is buried in something he says when describing the difficulty of moving on colleagues who have become tired in their roles: “The touchstone I always use is this: If my children were at the school would I be happy for them to be taught that subject by that person? And if the answer is no, then a difficult discussion has to happen.”

It is still raining as we head back towards the reception area and I spot two small boys dressed in yellow anoraks, speaking to one another in a made-up language, causing them to peal with laughter. Tweedale raises his shoulders and giggles along with them for a second before firmly shaking my hand and discussing follow up emails. An unusual mix of steeliness and warmth, indeed.

IT’S A PERSONAL THING

Favourite book?

The Harry Potter series. Our children were the right age to enjoy them and we ended up buying multiple copies as we were all reading them at once. It was a special time when the whole family was engaged with books.

Describe your perfect weekend

A competitive golf match, watching some sport, and spending time with my family away from work.

What was your favourite childhood toy?

In 1967 my dad went to Germany on business and brought me back the best leather football that anyone in Rochdale had ever seen. It became the talk of the street and it meant I was always invited to play every informal game of soccer with the “lads” playing with THE ball.

What was the best work advice you’ve had?

Two pieces of advice have resonated with me over the years: My dad told me the most difficult part of any job is getting it. And Ralph Tabberer [the former director general of schools] once told me that as a headteacher “people will listen to your words but judge you by your actions”.

Your thoughts