Oracy hit it big on the education agenda earlier this year when Nick Gibb unexpectedly dropped it into a conference speech, causing pundits to speculate whether it might replace phonics as the new darling of the schools minister.

As director of the oracy charity Voice 21, Beccy Earnshaw has seen the power of such pronouncements – the charity’s last conference quickly sold out, for instance. She’s also just landed a meeting with the schools minister, and her organisation is acting as the secretariat for a new all-party parliamentary group on oracy, which will be chaired by Emma Hardy, a former teacher and now MP for Hull West and Hessle.

Earnshaw is imprinted on my memory, however, as a mass of curly reddish-brown hair that yelled my name, then her own, as I steadied my bike one morning to avoid families walking to school through the Greenwich station underpass in south London.

I pondered the “Cath, it’s Beccy!” mystery for several days before receiving an email apologising for her shrieks and explaining that she lived around the corner from w’s offices, and, yes, she would be glad to take up my offer of an interview.

When I ring her doorbell two weeks later, I’m fully expecting a bubbly, larger than life northern lass. What comes as a surprise is the ceaseless stream of talk. I attempt to put her at ease by exchanging parenting stories while she makes tea.

There’s a circular feel to Earnshaw’s life, linking the northeast and London.

It’s so important that we bring in the whole range of voices

Born in Newcastle, the 40-year-old spent her secondary school years in Carlisle, did a broadcast journalism degree in Leeds, then moved to the big smoke in 1999 because she “wanted to go on the telly”. She joined “the very glamorous part of the BBC”, as a “caption monkey” for BBC Parliament, where she had to be able to recognise every MP so that she could bring their name up as soon as they started talking (and resist the temptation to put up ridiculous subtitles when parliament was sitting in the middle of the night and she thought nobody would be watching).

“I loved being in Westminster. It was just amazing and such a buzz. I used to have a pass for the House of Commons and would wander around at night, have my dinner in the Lords’ café and stuff. But then I just got really into the politics of it, and wanting to do something that was more that side of things.”

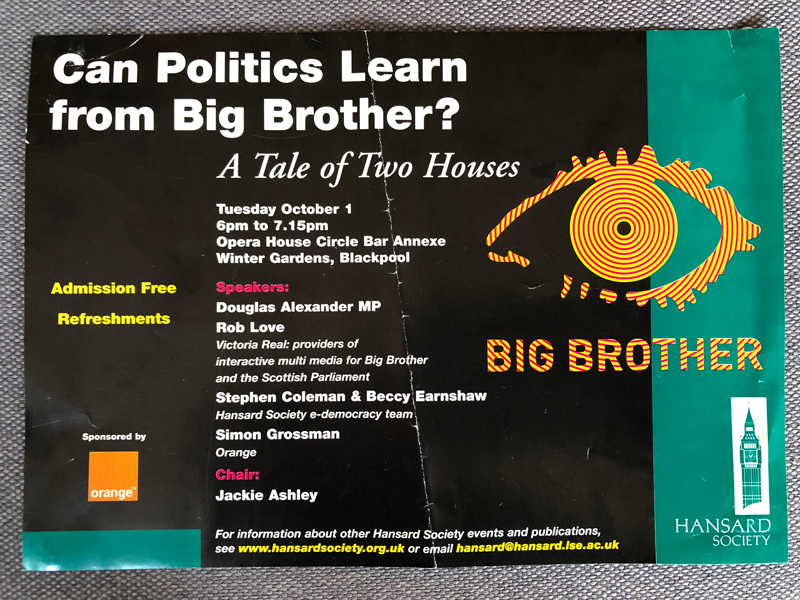

The Hansard Society fit the bill, and that was where she went next, looking at how to connect people more into politics, and piloting new methods of the public giving evidence, including citizens’ juries, forums, evidence-gathering for select committee inquiries, as well as the emerging world of online consultations.

It was the early days of the reality TV show Big Brother, a massive hit, and the commission decided to run an inquiry into what it could learn from it. “All the political junkies said, ‘Oh, we’ve got nothing to learn from people who like Big Brother, you know, they couldn’t tell us anything.’ Whereas all the Big Brother fans said, ‘I just don’t feel like I know enough about politics, but I think it’s really important. I wish I knew more.’”

She then took a similar role at the Electoral Commission, working on voter awareness and how to get young people involved.

Earnshaw was living with her husband, who works in advertising and whom she met at the age of 11 at her Carlisle secondary school. She tells a story of reconnecting on Twitter with Lisa Pettifer, her former English teacher, and telling her she’d met her husband at school. Her former teacher instantly new who he was. “It was clearly something that was discussed in the staffroom,” she says, slightly embarrassed.

At 29, after a short spell in the Children’s Commissioner’s office, the pregnant Earnshaw moved back to Newcastle and surprised herself and everyone else by landing a job as the first director of the charity Schools NorthEast, which started with a grant from the regional development agency, but now funds itself.

Fresh from Westminster, she was competing against local headteachers approaching retirement and others with long experience in local authorities. Fifteen heads split themselves into two interview panels and ran it like a teacher recruitment day.

“They didn’t know what they wanted,” she says. “I’m still in touch with a lot of the heads and they said it was a really heated discussion afterwards about the fact that I didn’t fit with anything they thought they were going to get, but they were going to take a punt and go a different way.

“My argument was always that they’re the experts in education. My job was to help them to have a better platform to be able to amplify their voices — somebody who was coming from a different perspective and being able to see which issues would cut through.”

It turned out to be a successful model, giving schools a voice regionally and nationally, and her successor, Mike Parker, is another ex-journalist.

After seven years of her husband commuting to London, they finally decided to come back to the capital.

“I should have sensibly spent some time moving the kids down, settling them in and everything. Eliza, my youngest, was just starting reception, and I’d missed all the deadlines for putting in school applications stuff. And we didn’t know where to live. But me being me, I saw the job at Voice 21, which was in exactly the same state as Schools NorthEast had been. It had been agreed as an idea, but that was it.”

Voice 21 was the brainchild of the founders of School 21, an innovative all-through free school founded in 2012 in east London that has embedded oracy throughout the curriculum. With funding from the Education Endowment Foundation, it had developed an oracy framework with the University of Cambridge and set up a charity to spread what it had learned to other schools. Start-up funding came from Big Change, the youth charity, and Earnshaw was hired to get it off the ground. After two years it works with 500 schools and has 16 employees.

She agrees with Gibb that talk in the classroom should be purposeful and high quality. One of the things Voice 21 does to develop “rich discussion” is to get teachers to assign “talk roles” in group work, with stem sentences for each role. “So the challenger might say, ‘Well, I would argue that…’ or the builder would say, ‘Connecting to your idea, could it be said that…’”

In an EEF pilot in 11 secondary schools, the first thing reported was an improvement in listening, which is vital, Earnshaw says. “If they’re not listening they can’t build on somebody else’s idea.”

Earnshaw is adamant that oracy is part of the key to narrowing the attainment gap. “If children are not in a language-rich home, and they’re not getting the language at school, where do we expect this to come from?”

She has now come full circle and is using the parliamentary structures to get more young people trained in speaking, so that they can participate in public life.

Children don’t feel that they’re heard

“Children don’t feel that they’re heard. What does that do to their confidence and well-being? The frustration that comes from not being able to express yourself, I think, is one that we see a lot in that link between young people with speech and language needs and people in the criminal justice system. It’s a huge connection. It’s frustrating.

“We often talk in Voice 21 and School 21 about disagreeing agreeably and a lot of the things that are at the heart of what it means to be a civilised society. To value democracy, to be able to deliberate about things, to be able to change your mind, to be able to come to a consensus — these are the type of things that we’re teaching every day in classrooms.

“I’m really conscious of the current situation, talking about Brexit – the insurgency of the unheard. I think there is something about who gets heard in our system and who doesn’t, and whose voices are valued and whose are not.

“That’s something I felt very strongly in the northeast, that it was very easy if you were a school that’s doing well in London to be able to rock up at an event in the Department for Education and be heard, and to get the plaudits and all that.

“It’s much more difficult for the school that’s grafting away in the northeast and doing amazing work in challenging circumstances, but never getting seen or heard. With anything we do, I think it’s so important that we look at how do we bring in the whole range of voices and those people who aren’t normally heard.”

Your thoughts