The Education Policy Institute has published its annual report, which has found that the attainment gap between poorer pupils and their better-off peers has stopped closing for the first time in a decade.

The report is based on government data for 2019, with warnings that gaps may be much wider still this year due to the coronavirus pandemic.

The EPI has called for “an urgent emphasis on closing gaps in education”, and said its research should serve as a “timely reminder that efforts to tackle the social determinants of education, such as poverty and trauma during childhood, are a fundamental to reducing educational inequalities”.

“It is widely expected that the Covid-19 pandemic will increase the disadvantage gap significantly. This, combined with the fact that the gap was already beginning to widen prior to the pandemic, suggests that without targeted government action to close the gap there is a risk of undoing decades of progress in tackling educational inequalities.”

Here, we take a look at some of the report’s key findings.

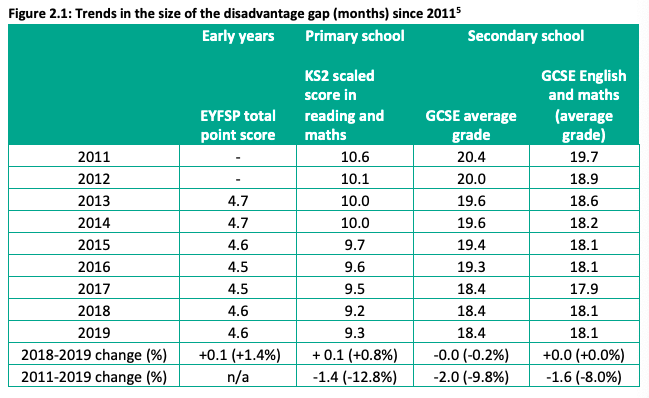

1. The disadvantage gap has stopped closing

EPI’s disadvantage gap measurement is formed by comparing the attainment of disadvantaged pupils – any pupil who has been eligible for free school meals in the past six years – and their peers.

This gap had been closing since 2011, but now stands at 18.1 months, the same as it was five years ago.

At primary level, the gap has actually increased slightly – from 9.2 to 9.3 months – for the first time since at least 2007.

2. Poverty plays its part

Since 2011, there has been less progress in closing the gap for persistently disadvantaged pupils – those who are eligible for FSM for 80 per cent or more of their school life – particularly at secondary level.

The EPI says that more recently, increases in persistent poverty among disadvantaged pupils have contributed to the halt in progress for the wider disadvantaged group.

Since 2015, those who were at a high persistence of disadvantage has grown by 5 per cent, while the lower persistence group shrunk by 18 per cent.

Persistently disadvantaged children were on average 22 months behind their more advantaged peers and this has not improved in the last decade.

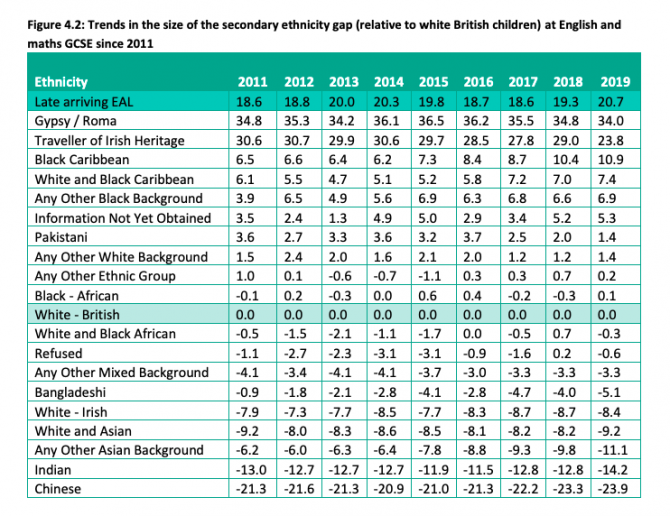

3. The gap has more than doubled for some ethnicities

The report also explored the attainment gap between pupils of various different ethnic backgrounds and white British pupils.

It found that the gap has widened by 4.4 months among pupils of a black Caribbean background, and three months among pupils of “any other black background”.

Gypsy and Roma pupils are now almost three years behind by the end of secondary school, and pupils of Irish traveller heritage are two years behind their white British peers.

Chinese pupils are two years ahead and Indian pupils are 15 months ahead (although EPI points out that these ethnic groups represent very small proportions of the total pupils population so are more skewed by individual outliers than larger ethnic groups).

EPI also found that at the end of primary school, late arriving EAL (English as an additional language) pupils are 15.5 months behind native English speakers, and this rises to 20.7 months at secondary.

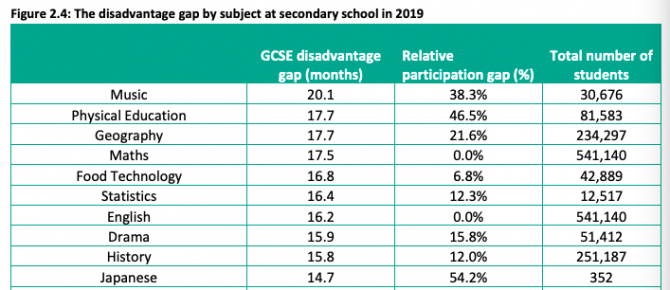

4. Music has the largest disadvantage gap

Disadvantaged pupils are 38 per cent less likely than non-disadvantaged pupils to take music at GCSE.

And when they do, their attainment is the equivalent of 20 months behind that of their wealthier peers.

It’s a similar picture for physical education, where there is a disadvantaged gap of 17.7 months and a participation gap of 46.5 per cent.

EPI say this may be driven by “parental investments” in sport and music outside of school, such as private music and swimming lessons, that are less accessible for disadvantaged pupils.

“Disparities in schools’ ability to provide equipment and facilities (such as playing fields and musical instruments) may also play a role,” the report reads.

5. And languages have smaller gaps

The EPI says that language subjects tend to have smaller disadvantage gaps, but points out that they are also taken by a much smaller share of the pupil population.

In some language subjects, such as Gujarati, Arabic, Persian, and Biblical Hebrew, there is a negative disadvantage gap – on average, disadvantaged pupils do better than their non-disadvantaged peers in these community languages.

“This may be because disadvantaged pupils who take these subjects are bilingual or fluent in these languages and thereby score more highly than their peers despite being socio-economically disadvantaged,” the report reads.

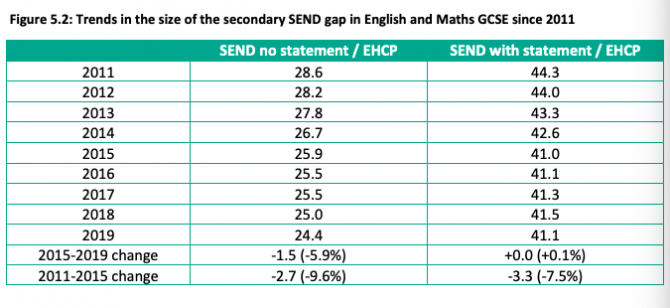

6. Progress in reducing gaps for SEND pupils has been slow

By the end of secondary school, SEND pupils with a statement or Education, health and care plan are on average over three years behind their peers.

Since 2015, progress in closing the gap for the non-EHCP SEND group has slowed, and it has stalled for those with an EHCP.

And the EPI says that overall progress has been particularly slow since the special educational needs and disabilities (SEND) reforms in 2014.

“While it is not possible from this research to conclude whether these changes are causally attributable to these reforms, we can conclude at best that they have not yet been effective in improving outcomes for SEND pupils, and at worst that their implementation may have been detrimental.”

7. Vulnerable pupils significantly behind their peers

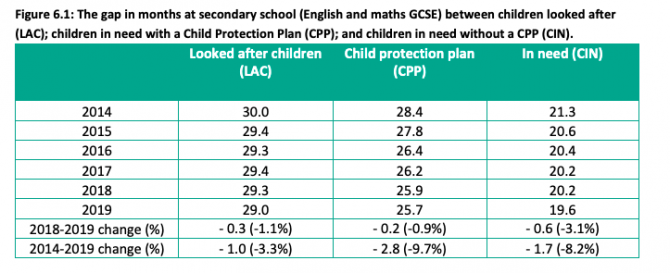

Pupils who are in the care system, have a social worker or are on a child protection plan are “significantly” behind their peers by the end of secondary school, the EPI found.

By the time they sit their GCSEs, looked-after children are 29 months behind their peers.

Meanwhile, children in need with a child protection plan are 26 months behind, and children in need without a child protection plan are 20 months behind.

Since 2014, the size of the gap has been decreasing for all three of the groups, but to differing extents.

Looked-after children have seen least progress, with the gap reducing by just a month.

The EPI points out that as these groups have grown (due to the bar for referring children to social services or placing them on a plan being lowered) the overall profile of the groups may have become less severely vulnerable, so therefore reducing the size of the gap.

8. Some areas have a disadvantage gap of more than two years

The EPI also broke down the attainment gap data by area, and found that Blackpool (26.3 months), Knowsley (24.7) and Plymouth (24.5) had the largest gaps in terms of GCSE English and maths attainment last year.

However, the EPI said caution should be used when interpreting how well LAs are doing in terms of their gaps, as it can be a “complex reflection” including socio-economic characteristics which can be beyond the control of schools and councils.

It has also brought in an “adjusted gap” measure to see what the gap is when each LA had the same level of persistence of disadvantage.

This measurement brought South Gloucestershire (25 months), West Berkshire (24.5) and Blackpool (24.5) to the top.

“For areas with high levels of persistent poverty such as Walsall, Knowsley, Newcastle upon Tyne and Portsmouth, adjusting for persistence reduces their disadvantage gap.

“This means they might not be doing as badly as the raw ranking suggests, given the profile of disadvantage they are dealing with.”

Your thoughts