Amarjit Cheema is not a “top down” academy boss who believes in dictating how her schools or communities should approach learning.

“The people in the classroom – they know what’s going on,” says the chief executive of the Perry Hall Multi-Academy Trust. “We’re very much about the individuality of our schools and their identity.

“If you look at the education horizon now, the big thing is about assistant-led leadership, not down-led leadership. It’s about getting people on side”.

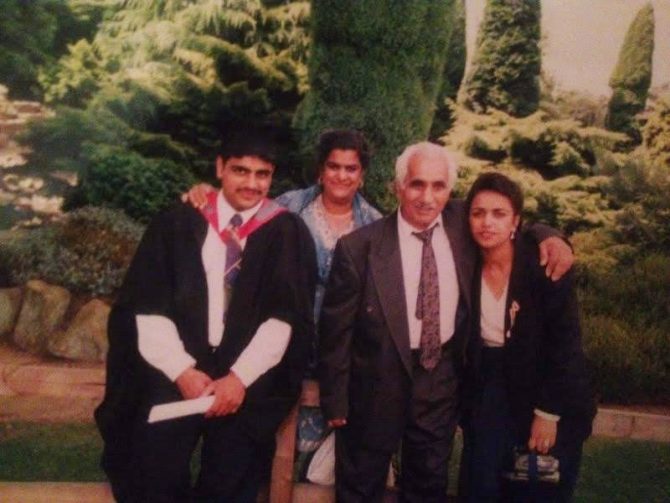

Cheema’s leadership was recognised this year when she was awarded the OBE in the Queen’s Birthday honours. When I ask why she thought she got the honour – which made her and her husband cry – she suggests: “I make sure everyone around me feels they’re valued”.

One teacher told me I’d amount to nothing

She oversees six very different primary schools across Wolverhampton, Staffordshire and Worcester: there is a “blue sky thinker” headteacher at one, a “systems and processes” head at another.

Leadership styles and the curriculum need to reflect their communities, while bringing about “change from within”, she says. At Dunstall Hill primary in Wolverhampton for example, 83 per cent of children have a first language that is not English, but just 7.5 per cent of pupils have the same profile at Berrybrook primary, also in Wolverhampton.

Listening to Cheema talk about her career, you can see how her approach has informed everything she does. But this skill of sharing leadership was not always her strong point. An undiagnosed dyslexic, school was a struggle and she was left thinking she needed to do everything herself. She tells of one of her harder moments at school in an English lesson. She was 15, but it “still brings a lump” to her throat.

“I’d worked out when it was my turn to read so that when it came to me I didn’t look foolish. My English teacher caught me at it, and he said you’re not paying attention and you’ll amount to nothing. I was put down two sets, into the ‘thicko’ class.”

After she began teaching she saw the member of staff again. “I said, ‘you don’t remember me, do you. You said I’d amount to nothing’. He turned to ash.”

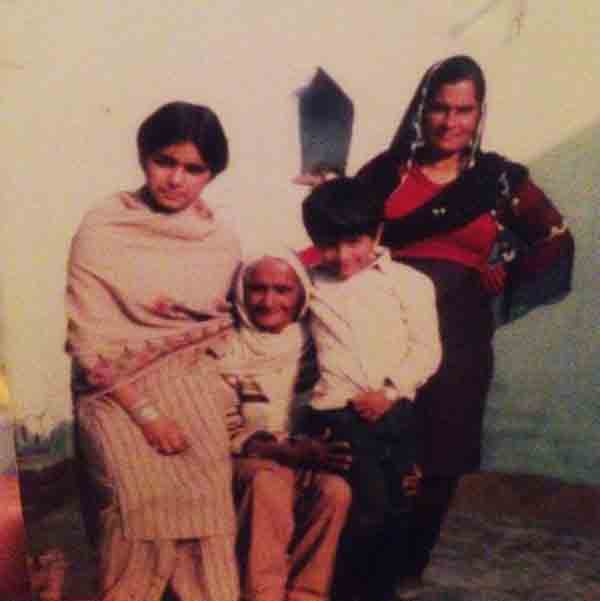

This gradual return to confidence followed an arranged marriage at 17 to an “amazing man” whose family believed strongly in the power of education and giving back to the community. Cheema took her maths GCSE while pregnant and at 21 became a nursery nurse.

Then she trained as a teacher and rapidly rose up the ranks. But when a headship in a medium-sized primary and a deputy headship in a large primary came up, her head advised she go for the deputy role.

“She said, ‘you need to learn to delegate’. I would just do everything myself, it was easier that way. On reflection, she was right.” In 2004 Cheema took her first full headship at Woodfield Infant School in Wolverhampton and in 2010 she became head at Perry Hall primary. Her two great lessons – never make a child feel small and share leadership – followed her.

“I always say to staff, ‘never shout at my children’. They’re small human beings, you gain their respect. And if you earn their respect, you’ve got them for life.”

The trust grew steadily. Perry Hall primary was the first school in Wolverhampton to convert to an academy and become a trust, taking on Berrybrook in 2014 and moving it from special measures to “good” by 2017.

Dunstall Hill joined in 2016, moving from “requires improvement” to “good” in April this year. In June 2018, Bird’s Bush primary, Tamworth, also in special measures and yet to be inspected, joined. In September last year, Woodthorne primary in Wolverhampton joined, followed in February by Stanley Road primary in Worcester. Both had been graded “good” by Ofsted.

The results since are quite astonishing: at Dunstall Hall, 70 per cent of pupils are meeting the expected standards in reading, writing and maths. At Perry Hall it is 81 per cent, compared with a local authority average of 65 per cent. A lower than average proportion are reaching expected standards at Berrybrook, but progress scores are above average in a school where 40 per cent of pupils are on free school meals compared with the national average of 14 per cent. Data for other schools is not available yet.

“The one thing I learnt quickly is that what system works in one school doesn’t work in another,” Cheema says. “A lot of trusts would say differently.”

One of her heads, who deals with behaviour issues to help pupils become more respectful, works best with a team that oversees “the mechanics”, she says. Another head with a more “volatile” community focuses on processes to help staff to feel more secure.

“The leaderships are different, but it works for their communities.”

Cheema’s empowering approach is now being tested as her team designs a PSHE curriculum against the backdrop of protests from some Muslim parents in nearby Birmingham to LGBT relationships education. Cheema is frank about her approach.

“We have a core curriculum, but it will be adapted to meet the needs of those communities. If I turned around and said ‘this is what we’re going to do’, I would lose some very good staff.

“In some of our schools we have a high Muslim community, and we’d be foolish to put this in as a specific module. It’s about talking about healthy, positive relationships.” Parents have also been invited to give their thoughts on the new curriculum. How LGBT relationships are taught, “needs to be up to schools”, she says.

Yet despite her strong belief in the individual identity of communities, Cheema rejects the idea that her Sikh family background helped her to reach out; instead, she attributes her successes to listening and having high standards. She relays a headship interview which left her “fuming”: “The panel asked me, ‘you’re young, you’re brown and you’re a woman. Tell us how you will win our community over’.

“I sat there and said, ‘gosh, I must go and dust my mirror down’. Did those words seriously just leave your mouth? The difference is your approach as a leader.”

What works in one school doesn’t work in another

Cheema believes in creating “change from within” – she trained as an Ofsted inspector when she became a head so that she could understand the accountability system.

“If the governing body has appointed you to make sure the children get the best education they can, the best way to do that is from the inside.” Her advice is to “make sure the information you’re relaying to the inspector is accurate and clear and you sell the best things about your school”. She says her Ofsted training was fantastic, and challenges those who would scrap it.

Cheema appears to have the rare quality of speaking her mind while encouraging others to speak theirs. Now her trust has applied to open a free school in Tamworth and wants to grow in Worcester. Perhaps heads who miss their autonomy should apply.

Your thoughts