Over a third of state schools now allow pupils to opt out of studying a language in year 9, a new report has revealed.

In fact, 34.5 per cent of state schools are not teaching modern foreign languages (MFL) to entire groups of students at that level, up from 29 per cent in 2017 and 26 per cent in 2016, according to the British Council’s 2018 language trends survey.

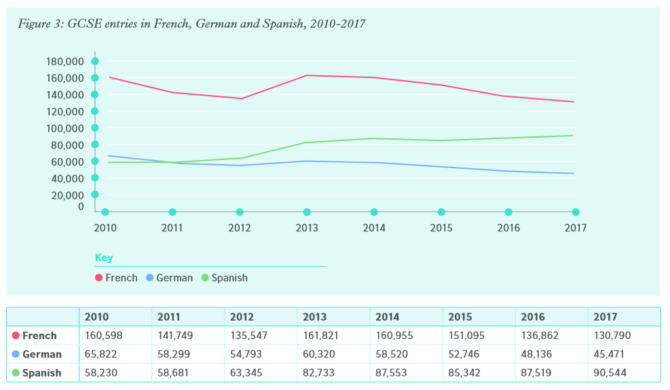

The declining interest in MFL is an ongoing problem. In June 2017, Ofqual’s figures showed summer entries for German GCSEs and A-levels had dropped by 12 per cent, with French falling by 10 per cent, and Spanish by three per cent.

In August of the same year, overall entries for MFL exams had fallen by 7.3 per cent to around 300,000 in total.

At the time Suzanne O’Farrell, a curriculum and assessment specialist at the Association of School and College Leaders and a former head of languages, said “something radically needs to be done” to prevent MFL from becoming “extinct in schools”.

The British Council’s new report found that the overall proportion of pupils taking a GCSE in a modern language fell by two percentage points to 47 per cent in 2017, and that just a third of all students obtained a grade C or above. Schools in the most disadvantaged circumstances were less likely to push languages courses.

Schools in the most disadvantaged circumstances were less likely to push languages courses.

At key stage 3, only 22 per cent of schools with the highest free school meal eligibility said they teach languages for 2.5 hours or more, compared with 55 per cent of schools with the lowest FSM eligibility.

MFL continues to be popular in selective schools though, where 76 per cent of the cohort took a language in 2017. There was also higher than average take-up at free schools and converter academies.

But in sponsored academies only 38 per cent of pupils took a modern language, falling to 27 per cent at university technical colleges and 15 per cent in studio schools.

Both state schools and independent schools reported that lower-ability students were less likely to take a language GCSE than before, due to the recent introduction of the more rigorous GCSEs.

Vicky Gough, a schools adviser at the British Council, said the opportunity to learn a language “should be open to everyone, regardless of what kind of school they attend”.

“Learning a foreign language can open doors, not only by helping us understand other cultures but also providing vital skills much sought after by employers,”she insisted.

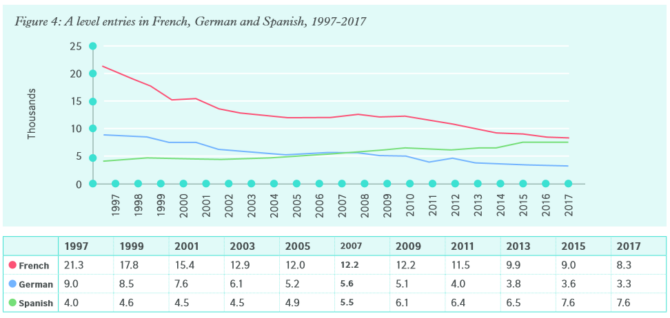

The outlook for Spanish is much better than for French and German, where uptake at GCSE and A-level has dramatically fallen over the last two decades.

The report predicts that based on current trends, Spanish will overtake French as England’s most widely taught modern language at A-level by 2020 and at GCSE by 2025.

“At a time when it is more important than ever that the UK forges new relationships around the world, languages need to be championed and treated as a national priority so that young people are equipped with the knowledge and skills to live and work in a global economy,” Gough added.

The language trends survey of primary and secondary schools in England has been gathering information since the subject was removed from the compulsory curriculum at key stage 4 in 2004.

This year’s survey was carried out from January to March this year, and gathered evidence from 692 primary schools and 785 secondary schools (651 state-funded and 134 independent).

Year 9 students are opting out of languages this week and 90 percent of them have no motivation to keep on doing French or Spanish anymore.

As an NQT teacher I would be very grateful if someone with more experience could tell me how to keep these students engaged in lessons. I have been asked this questions in many of the job interviews I had as an NQT and I did by best to give common sense and sensible answers but it seems that it is a hard question to answer.

Thank you