A quarter of teachers work more than 60 hours per week, according to a new study, which warns government attempts to reduce working hours have failed.

But the paper, published by the Nuffield Foundation and UCL Institute of Education, also found high working hours have been relatively unchanged for 20 years – making it unlikely that workload is to blame for the teacher retention crisis.

Policymakers have now been urged to consider “more radical action” to tackle the workload issue.

The report, published today, said teachers work an average of 47 hours a week in term time, eight hours more than teachers in comparable OECD countries.

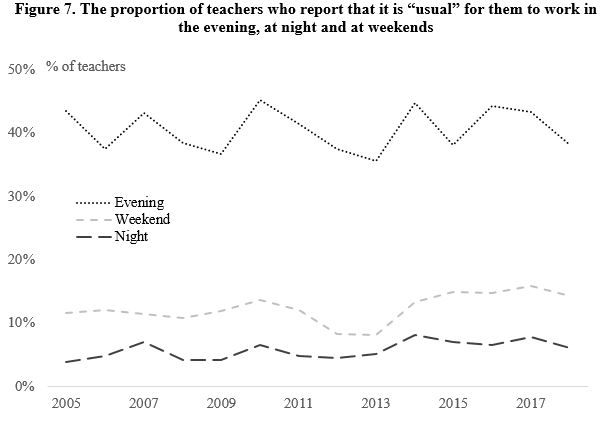

One in four teachers work more than 59 hours a week, while 10 per cent work more than 65 hours per week. Around 40 per cent said they usually work in the evening, and 10 per cent during the weekend.

However, it said these hours – although “high” – had been broadly the same for the last two decades and were “unlikely” to explain declining teacher retention.

“We do not find evidence that average working hours have increased. Indeed, we find no notable change in total hours over the last 20 years, no notable change in the incidence of work during evenings and weekends over a 15 year period and no notable change in time spent on specific tasks over the last five years,” the report said.

It warned “five years of policy initiatives” aimed at reducing hours have “proven insufficient”, and bringing working hours down will “require additional, more radical action on the part of policymakers”.

Kevin Courtney, joint general secretary of the National Education Union, said 60-hour working weeks are “completely unacceptable” and “successive education secretaries are failing to solve the problem”. He blamed the Department for Education and Ofsted for the “culture of excessive accountability” that has driven up workload.

The report also said workload “may have been given undue emphasis in the debate on teacher retention” and recommended the government focus on other ways to improve retention, including increasing pay, improving leadership and better working conditions.

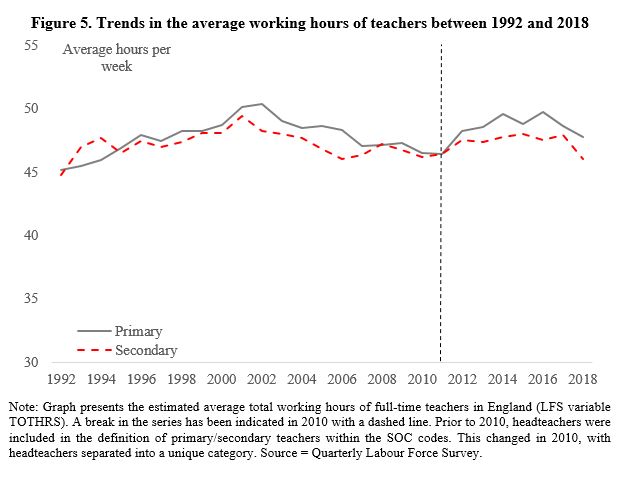

The study found over the last 25 years secondary teachers have worked between 46 and 48 hours per week, with the highest level recorded at 49 hours in 2001, suggesting the current 47 hours is not “outside of their historical norm”.

Primary school teachers worked an average of between 47 and 49 hours per week in the same period, reaching its highest point of 50 hours in 2002.

In the last five years, there is “little sign of any substantial reduction” in the time spent marking (6.3 hours per week in both 2013 and 2018) or administration (4.2 hours in 2013 and 4 hours in 2018), while any “minor reductions” in lesson planning and extracurricular activities have been “offset by increases in pupil guidance/discipline and ‘other’ (undefined) tasks”.

Full-time secondary teachers spend almost as much time on management, administration, marking and lesson planning each week (20.1 hours) as they do on actually teaching pupils (20.5 hours).

A spokesperson for the DfE said it is “making concerted efforts to reduce workload driven by unnecessary tasks”.

Excessive teacher workload is a persistent problem because governments constantly raise the bar on what they expect from schools

“We will continue our work within the sector to drive down these burdensome tasks outside the classroom so that teachers are free to do what they do best – teach”.

However Geoff Barton, general secretary of the Association of School and College Leaders (ASCL), said “excessive teacher workload is a persistent problem because governments constantly raise the bar on what they expect schools to do”.

“Various initiatives have been launched to reduce workload in recent years but schools have been swamped by changes to qualifications and testing, relentless pressure on performance and results, and funding cuts which have led to reductions in staffing and larger class sizes.”

The report called for the DfE to reform its workload survey, which has very low response rates and “adds little value over other routinely collected data sources”.

The study was based on data collected from more than 40,000 primary and secondary teachers in England between 1992 and 2018 by the Labour Force Survey, the Teaching and Learning International Survey, the UK Time-Use diaries and information gathered from the Teacher Tapp app.

Did (any of) the 40000 or so teachers providing the data quit and then say that quitting wasn’t because of workload? If not, it’s not in fact possible to conclude from the data whether or not workload issues have been causing a crisis in retention. Given it’s not a particularly obvious conclusion to draw anyway from the data, you would then also have to wonder about the bias of the person/s who initially drew it.

Don’t question the study, it’s based on information from Teacher Tapp.

My wife is Assistant Headteacher, SENCO & Reception Teacher and works from 8-5 plus 2-3 hours most evenings and an average of 6 at the weekend, totalling 66 hours.

Budget reductions means less staff and those that are retained have to wear many hats to complete the utterly ridiculous expectations of local and national government.

Result: teaching suffers; quality of lessons is poor and all for working extremely hard for what equates to less than the minimal wage.

AMEN!! I’m so sick of lesson quality taking a back seat to absolutely everything else! As long as marking and books, data, displays and pupil progress meeting files look good, then the education must be good too, regardless of lessons – it’s a joke. Everything that counts towards a good looking education is far too easy to fabricate.