In a five-part series, Schools Week is exploring the way vulnerable groups of learners have been treated under the Coalition – and asks what can be expected for them in coming years. In this second instalment, Ann McGauran reveals that narrowing the stubbornly high achievement gap for children in care remains a significant challenge

The stark facts show the attainment gap between looked-after children (LAC) and their peers is not going to close any time soon. But what has the government achieved in this area for young people in care – and those leaving it – over the last four years? And what remains to be done?

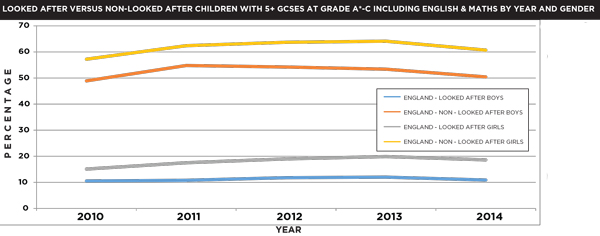

In 2010, 12.4 per cent of LAC achieved the benchmark of getting five or more A* to C GCSE grades, including English and maths, compared to 52.9 per cent of other pupils. By 2014, the figure for LAC rose to 14.4 per cent, but that for their peers had crept up to 55.4 per cent. The gap between the two groups grew instead of closing.

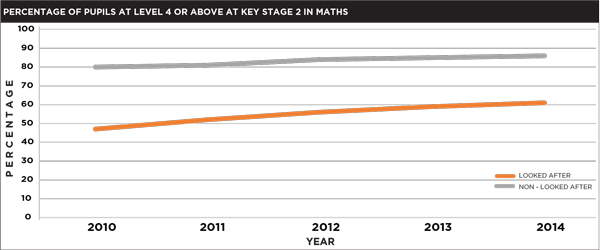

Among younger children the picture is somewhat better. In 2010, at Key Stage 2, 47 per cent of LAC reached level four or higher in maths, versus 80 per cent for other children. But by 2014, 61 per cent of LAC were achieving that level, while the figure for other children only grew marginally to 86 per cent.

Previously the gap was closing more quickly, but this was likely due to the shockingly low base. In 2006 only 5.6 per cent of LAC achieved five or more A*-C GCSE grades, including English and maths. That is just one in 18.

Chief inspector of schools and head of Ofsted Sir Michael Wilshaw told a public accounts committee hearing in January that attainment for children in care is “shockingly poor” and the gap between them and their peers too wide.

In light of his comments, Schools Week asked Jane Pickthall, North Tyneside’s head of the virtual school for LAC, to assess progress on care leavers since 2010. She’s is complimentary about the role of the Coalition, and in particular, that of children and families minister Edward Timpson. “He has been amazing. He grew up in a family that fosters, and this has been something very close to his heart.”

The role of virtual school heads

Virtual school heads (VSHs) have a primary focus of raising the educational attainment of children in care by getting them the support they need. VSHs track the progress of LAC in a local authority as if they were in a single school.

The role was made statutory last May. While this has improved the status of VSHs, Ms Pickthall says there is still considerable variation between different local authorities in terms of where the role sits. “The higher the tier the more strategic impact and influence the VSH can have”.

She calls the introduction of the £1,900 Pupil Premium Plus – available for each LAC from the first day they go into care and managed by the VSHs – “a big boost”. Ms Pickthall believes its existence has improved dialogue between VSHs and schools, as well as making it easier to target resources to meet individual needs. But as she notes, the “key question will be – can we make a difference with it?”

She says the Department for Education has been “really supportive” to VSHs and helped set up a national association. The VSH steering group has begun to meet regularly with Ofsted at both a national and regional level to raise awareness of the role, the needs of LAC and consider how the inspection regime might focus on their quality of education.

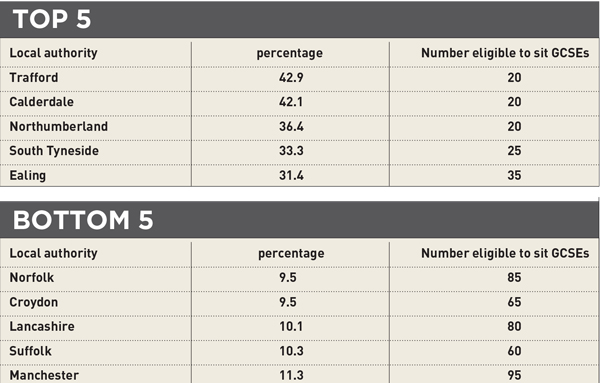

Why are there such wide variations in outcomes for LAC across different local authorities? “The same can be said for other vulnerable groups and at the end of the day the quality of the schools that children attend makes a big difference.”

The fledgling national association would like to see a change to the data collection, “so that we have a more meaningful measure of the impact of care”. It would like to see a progress measure from the time when children first go into care, a breakdown by placement type, and links between long-term outcomes and both special educational needs categories and strengths and difficulties questionnaire scores.

A focus on getting the right data is crucial, says Professor Judy Sebba, director of the Rees Centre for Research in Fostering and Education at the University of Oxford. She says it is “particularly damaging to move a child in the last two years of school – but we are trying to work out how much is caused by moving placements and how much from moving schools”.

According to Professor Sebba, the distance from home in which young people are placed is often problematic, “as support services are often set up for local people and not conducive to helping young people who are a long way from their place of origin”.

Being far from home can impact schooling, as students must travel longer distances, or – in extreme circumstances – be forced to change school.

Professor Sebba emphasises the research evidence for fostered children would say that “the most important thing is for the school, social worker and foster carer to work together. The foster carer needs to be engaged and helped to provide educational support”.

A care leaver’s perspective

What’s the care leaver’s perspective on how they can be supported? Aine Kelly is well-placed to know about this – as the 27-year-old is a former care leaver and is currently a doctoral student at Green Templeton College at the University of Oxford.

Based at the Rees Centre, she is undertaking a PhD on improving the health of LAC. Physically and emotionally abused and neglected as a child, she says she had “a lot of foster placements” and missed a lot of school. By the time she got to secondary school, she believes that people “didn’t really understand what had happened to [her] and [she] had average grades”.

By that stage Ms Kelly did not want social services involved with her schooling, but, with hindsight, she concedes: “I think I would have benefited if social services had been more involved. They could have gone about it in a different way that did not identify me as a LAC– but still gave me the help I needed.”

Ms Kelly, who shared with Schools Week five points for schools (see right) to help them address the needs of LAC, has come a long way. “I have co-taught a few sessions with the VSH for Oxford for future teachers, telling them the things not to do.”

When it comes to that attainment gap, what’s the outlook for the next generation of care leavers? Ms Pickthall is cautiously optimistic: “We believe there needs to be a sea change to make a real difference, otherwise we will only continue to improve in small steps.”

DFE STATEMENT

“We know that the attainment gap between looked after children and their peers remains too wide – but progress is being made.

“As part of our plan for education, we have introduced a comprehensive package of reforms to close that gap through a combination of support and additional resources including a ‘pupil premium plus’ for looked-after children which is worth £1,900 per pupil in 2014-15. That is double the amount for the previous year.

“We have also made it a legal requirement for every council to have a Virtual School Head to provide clear leadership and support for looked after children in their area, ensuring they are receiving help and support.

“At primary school level, our most recent statistics show that the gap between children in care and their classmates has narrowed in both maths and reading by eight percentage points since 2010. There have also been falls in absence and exclusions for looked-after children.”

Aine Kelly’s five points

- Try to find the one thing the young person is good at

- Understand there is always a reason behind the behaviour

- Praise them: “We don’t get that enough”

- Do more about teaching life skills

- Professionals need to work together as a team

Case Study: Secondary School Outcomes for Young People in Care

A research study to identify the key factors associated with low educational outcomes of young people in care in secondary schools in England is being carried out by the Rees Centre for Research in Fostering and Education and the Education Department, University of Oxford and researchers in the School for Policy Studies and Graduate School of Education at the University of Bristol.

Funded by the Nuffield Foundation, work on Educational Progress of Looked-After Children Ð Linking Care and Educational Data – began last February. Data collection will finish at the end of June.

The research is co-directed by Professor Judy Sebba and Professor David Berridge. The study looks at the relationship between educational outcomes, young people’s care histories and individual characteristics by linking the National Pupil Database and the data on Looked After Children for the cohort who completed GCSEs in 2013. Outcomes for children with different characteristics Ð for example gender, ethnicity and socio-economic status and the relationships between outcomes and length of time in care, school stability and placement type and stability are being explored.

The study will also include interviews with 36 young people in six local authorities and with significant adults such as teachers, foster carers, social workers and Virtual School staff. The interviews look at what could be done to improve the progress of pupils in care and how better coordination of services might help. The research will identify types of data and how data collection might be improved to enable better use of it in future. The report will be published in the second half of this year.

Your thoughts