The new maths GCSEs were designed to be different from the old A* to G GCSEs, says Cath Jadhav, so you really can’t compare new and old.

Over the next two months we will be reporting on various aspects of summer 2017, including official statistics.

Our very clear aim, in planning for the first new GCSEs in summer 2017, was that the transition should be as smooth as possible, and that the students taking them would not be unfairly disadvantaged by being the first to sit these new qualifications.

The transition to the new GCSEs was generally smooth. In maths, schools appear to have made appropriate tier entry choices for their students: there were fewer students this summer who were ungraded on the higher tier and no students scoring full marks on the foundation tier.

The new maths GCSEs were designed to be different … you really can’t compare new and old

However, some commentators expressed concerns about the grade boundaries in GCSE maths. Much has been written about the ‘low’ grade boundaries and how they are lower than previous years. This has been interpreted as Ofqual lowering the boundaries in the first year of a new qualification.

Unfortunately, it’s really not that simple. The new maths GCSEs were designed to be different from the old A* to G GCSEs, so you really can’t compare new and old. Here’s why.

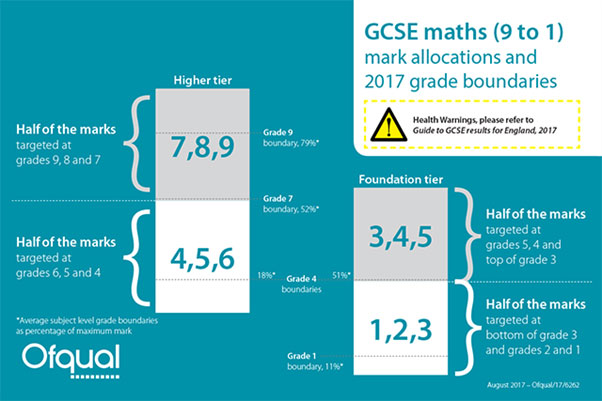

First, the available grades on each tier are different and the overlap grades are different. Previously the highest grade on the foundation tier was a C.

In the new GCSEs, the highest grade on the foundation tier is a 5, a grade which spans the top of a C and the bottom of a B. The overlap grades –those available on both tiers – are 5, 4 and 3. That’s higher than the overlap on the previous qualifications of C, D and E, which probably explains the shift towards the foundation tier entry this year.

As well as those differences, for the first time we also set specific rules about how the papers should be designed. Why do that? Higher tier papers must strike a balance between testing the content aimed at grade 4 and 5 students, and providing challenging questions on the grade 9 content and it’s important that exam boards are consistent in this. Our rules say that:

-In a higher tier paper, half of the marks should be targeted at grades 9, 8 and 7 and the other half of the marks should be targeted at grades 6, 5 and 4.

-In a foundation tier paper, half of the marks should be targeted at grades 5, 4 and the top of grade 3 and the other half of the marks should be targeted at the bottom of grade 3 and grades 2 and 1.

This is shown in the infographic below. Targeting questions is always tricky, but this means that higher tier papers now contain more demanding questions and only about a sixth of the marks on those papers are designed for students working at grade 4. In that context, it’s not surprising that the grade boundary for a grade 4 on the higher tier papers was around 20% of the maximum mark. But that doesn’t mean there is anything wrong with the papers. Rather, it’s a consequence of having to discriminate more at the top end but also provide sufficient challenge across the ability range.

If there were more marks targeted at grade 4, grade boundaries might be higher, but exam boards would be criticised for making their papers too easy, and it would mean fewer marks available to differentiate the very good students at the top end.

As schools and colleges become familiar with the new assessments, we might expect performance to improve slightly. And of course, grade boundaries will be set each year to reflect the difficulty of the papers. But we should not expect to get to a position where students have to score 50% of the marks to achieve a grade 4 on a higher tier paper, unless we redesign the papers to include many more questions targeted at grade 4.

Cath Jadhav is associate director for standards and comparability at Ofqual

Your thoughts