Amanda Spielman, Vicky Beer, Dame Rachel de Souza, Lucy Heller, Rebecca Clark, Janet Renou, Sally Collier: never has education had so many senior leaders that are women.

And whilst we should celebrate the growing number of women in these positions, the truth is that we would have even more women in leadership roles were it not for the barriers and attitudes that sadly still prevail in education.

Education comes pretty near bottom of the class when it comes to making strategic moves which would enable women to progress to the top. Financial services, tech, retail – have all recognised the need to change the way they think about their female employees and the support they provide. Nurseries and creches, spaces allocated for breastfeeding, genuinely flexible hours: these are all becoming increasingly commonplace in many a workplace, but rarely in education.

I would urge women who are progressing up the ranks to get a mentor who is a woman

And, as a result, too many women in the most senior positions in education are still having to choose. Sometimes between having children at all, other times – as I did – to having only one child. These are choices that no one should have to make, and yet whilst we are certainly seeing more women in senior positions, that has often come at a very high personal cost. I know it did for me, and it is something that I think about a lot.

But it’s not just about how we organise our physical assets, or our working days. Some will see this as controversial, but education suffers from acute everyday sexism. Much of it may be subconscious, but education is rife with it. I have sat on interview panels where male members of the panel have made key decisions about whether to hire a candidate based on her attractiveness, rather than her ability to do the job. Male employers also think nothing of phoning at all hours, or expecting meetings when it suits them – without a thought as to whether that means a parent is missing out on reading to their child, or if it is the only time that week they have had a chance to speak properly to their partner about anything other than just household logistics on bins, school runs and buying milk.

That’s why at Astrea I love and value it when a colleague says: “I can’t that day it’s my child’s nativity” or: “I can’t dial in as I’m doing school pick up”. An organisation must be able to ‘flex’ to respond to individual needs – be that secondments, moving to part time, or negotiating a period of absence. Decisions should be made with people in mind, not policy.

I know that many of my peers share my impatience and frustration at the pace of change, and so in the meantime I would urge women who are progressing up the ranks to get a mentor who is a woman and to make the time to meet with her regularly.

My own mentor has been an utter inspiration to me, and I’m sure she wouldn’t mind me sharing what I consider her most important piece of advice: remember it’s a marathon, not a sprint. Take time when it’s important – family and friends should trump everything else. Any sense of urgency is self-determined not set by others.

As for my own advice to those moving into leadership positions – in all honesty, the most important thing any woman can do is to make sure that whomever you choose as a partner is genuinely happy and able to support you. And if you have children? Get really good childcare.

Today’s working environment in education typically means that it is not simply a question of whether you think you are capable of taking the next step up when it comes to leadership. Until we have a more receptive and responsive system, it is more a question of whether your life can support that step.

This is an issue that affects not just women. As the stereotypical male/female accepted norms continue to dissolve, leaders of both genders are having to make these choices.

The balancing act can feel like a never-ending tightrope walk, and too many talented women progress no further than middle management. Too often, they feel that the sacrifices do not outweigh the benefits. Too many of us suffer from “good-girl-itis”: eager for praise and waiting for that all-important external validation. But of course, to truly direct one’s own career, that validation must come from within first.

And until we have a sector that actively embraces and values the joyous complexity of our lives and the things that make us capable of being leaders in the first place, we must continue to challenge and test behaviours and attitudes that prevent us from rising to the top.

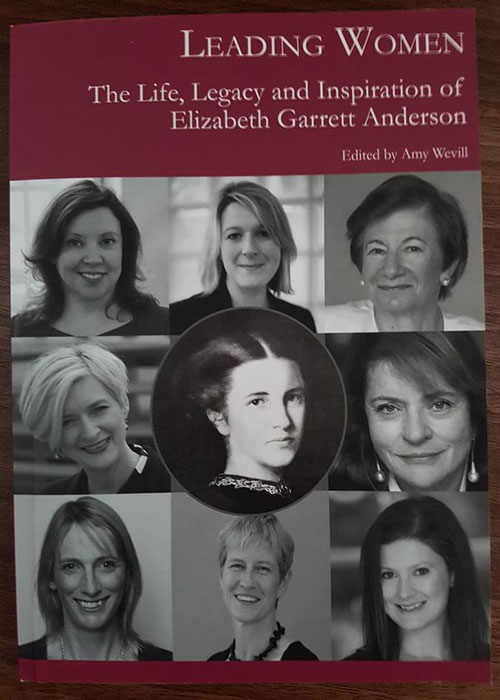

Piece taken from the collection of essays, ‘Leading Women: The Life, Legacy and Inspiration of Elizabeth Garrett Anderson’ by Wild Search. Available to download here. Libby Nicholas is CEO of Astrea Academy Trust

It’s noticeable that so many of the names above don’t actually teach a classroom of children. Some of them may once have done so but they don’t now.