It seems impossible that nearly 50,000 pupils disappeared from schools last year for no apparent reason. But this is exactly what the Education Policy Institute’s most recent report revealed last week: between 2016 and 2017, one in twelve students didn’t progress from year 10 to 11 in the same state-funded secondary school, for reasons that weren’t a permanent exclusion or family move, or switching to a higher-rated school or special school.

There are other reasons why this might be. Families might put their child into private schools, for example. Yet we’d expect this sort of decision to happen more in other year groups, given the substantial negative consequences for children switching amid their GCSEs. For several years, therefore, there’s been a growing feeling from journalists and politicians that perhaps these children are being forced out of the schools to shunt their results from league tables.

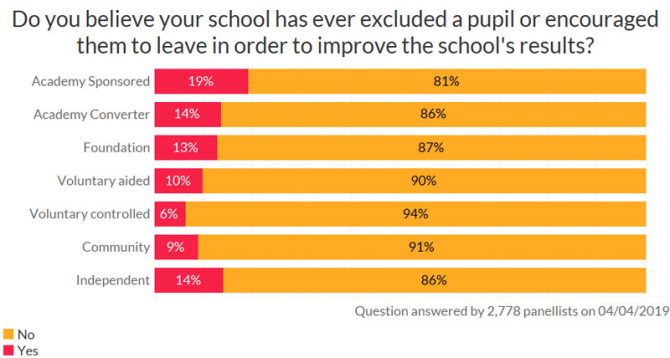

According to our recent Teacher Tapp survey data, teachers are sharing this growing feeling.

It all feels like rather slow progress

Among our panel of more than 3,000 teachers, 14 per cent said their school had formally excluded or encouraged a pupil to leave “to protect the school’s exam results”. That figure is higher in secondary schools, and particularly in those rated Requires Improvement or Inadequate. In these schools, 22 per cent of teachers reported cases of missing pupils, many of whom never pop up again in someone else’s classroom.

One of the many problems with the current accountability system is that students who leaders can see are likely to get very low progress scores will contribute negatively to performance measures. Being under pressure to turn around a poor Ofsted judgment (particularly if there is a fight for pupils to fill places), creates a strong incentive to engage in a game of pupil pass-the-parcel.

We found that school type matters for off-rolled students. In sponsored academies – the schools forcibly taken over because of poor historic performance – one in five teachers said their school had excluded students to protect results. That is the highest across the state sector.

Why? One hypothesis is that sponsored academies are under huge pressure to improve their results.

Think not, however, that this means those outside the accountability system escape the pressure. Private schools often ask students to leave to protect their results too. There are no regulatory controls in this sector – something that we should remember and therefore treat their headline exam results with a pinch of salt.

What’s possibly most alarming is a double incentive to push out pupils with special needs. Cash-strapped schools with resource units for special educational needs can off-roll pupils halfway through the year, neatly dropping their results, but still keep their £10,000 from the local authority. For schools struggling to stretch funds to pay their teachers adequately, extra dosh becomes attractive.

At various times the government has said it would remove the “perverse incentive” by making schools accountable for the exam results of pupils until they’re in another permanent school. Alternatively, schools could receive a percentage of the grade score, proportionate to the time pupils stayed at the school.

Angela Rayner, the shadow education secretary, has now committed to doing the same. Ofsted too is proposing to track schools with exceptional exclusion rates to clamp down on ousting kids for self-gain.

It all feels like rather slow progress, however. These issues were first mooted in 2010 and the whole thing has got worse since. The fixes are reasonably quick and it’s beyond bewilderment why they haven’t yet happened. Fifty-five thousand children are relying on us to solve this problem. There’s no time to wait.

Thanks for publishing this, and for feeling the same sense of urgency that so many parents do. Sadly, it is only the tip of the iceberg

Not just do some schools cull students with SEND while pocketing the funding, many schools and colleges aren’t letting them in in the first place. Some do it by the age old tactic of putting parents off, and making a feature of their lack of provision (aka lack of inclusiveness), others openly declare their intention to break the Equality Act 2010 and the SEN Code of Practice in letters to parents and minutes of governors meetings when they say that they are so short of cash that they’ll have to refuse to accept pupils with SEND.

I wonder if it would be possible for Schools Week to ask the TeacherTapp panel if they’re aware of this happening and to ask the members from primary schools if they’re aware of similar behaviour just before the KS2 sats? The answers may well make grim reading, but acknowledging it’s happening is the first step towards making a fairer system for all.

Am I the only person uneasy about the relationship between Schools Week and TeacherTapp?

TeacherTapp is a private, profit-making business that seems to be owned 50% by Laura McInerney. It promotes itself to businesses as way of “gaining fast insight into the products and services that teachers want and need (and how leaders decide to buy them)”, and currently charges them about £1,000 per question according to their website. It also says it can help researchers and policy specialists by getting them insights to their questions “within hours”.

Laura McInerney is also ‘contributing editor’ on Schools Week, and before that was editor for three years.

More and more articles and stories are being published by Schools Week which refer positively to TeacherTapp. Abandoning any pretence of impartiality, the article above is written by a TeacherTapp intern promoting its latest ‘survey’.

The more stories are published, the more awareness and presumably the more teachers sign up to TeacherTapp. The more Schools Week reinforces its credentials the more it is seen to have value – you only have to look at the comment above which is asking for TeacherTapp to be used to take the place of proper investigative journalism.

The more teachers, the more stories, the more kudos, presumably the more businesses will want to use TeacherTapp and the more that TeacherTapp can charge its customers, and consequently the greater the financial rewards for its shareholders. And yet nowhere does SchoolsWeek acknowledge the potential for conflict of interest given Laura McInerney’s role in both organisations.

I’m not alleging any actual impropriety because I don’t have any concrete information (none of us do). But if an academy trust was constantly promoting the business of one of its Trustees Schools Week would quite rightly be challenging it and shouting about it from the rooftops. Double standards at play here ?

Schools Week is, a privately owned business that tries to make a profit from monetising teachers and other interested people by getting them to click on links and subscribe to it. I don’t think it’s ever claimed to be anything else, so drawing an analogy between it and academy trusts which receive state funding to provide educational services and should be accountable to government for that money seems a little strange to me.

It is not compulsory to read it or to subscribe to it or Teacher Tapp, so I don’t feel uneasy about it because it’s what journalism is like in the digital age. Cross-selling is simply something that happens, although I have to say that I hadn’t noticed Teacher Tapp before, so it can’t have worked all that well.

If anything, I’m uneasy that your response to this article is to try to discredit the source of it even though the data broadly mirrors the conclusions reached by OFSTED and the EPI.

Sorry, no. Schools Week describes itself, on its own website, as “in-depth, investigative education journalism”.

I believe that any publication that holds itself out in that way has a duty to be open and clear with its readers. There is a also a huge difference between charging subscriptions and having paid adverts, which is done openly, and under-the-table enrichment of an interested party (if that is indeed what is happening here, which I’m not saying it has).

Every newspaper produced in the UK sells hard copies to its readers, and advertising space to businesses. That’s the model. But if the Sun produced story after story which promoted a business which was never openly acknowledged to belong to the editor, that would be a problem. It’s why newspapers have to print “this is an advertorial” etc. on pieces that have been paid for. Even in the Wild West of social media, we now have an expectation that bloggers/tweeters make clear when there is a financial interest behind what they’re saying. I agree with you that “cross selling happens”, but when it does we have a right to know about it.

The whole point of my post was that we simply don’t know what’s going on here. Are Schools Week reporters encouraged to base articles on TeacherTapp? Are they discouraged from questioning the results? We don’t know.

Why doesn’t Schools Week have a standard disclaimer that’s published whenever TeacherTapp is referred to, pointing out the relationship and letting the reader make up their own mind?

And two final points:

1. TeacherTapp is an excellent app that is really useful at producing quick results. It’s not the same as proper investigative journalism, but is showing itself to be a really good part of the bigger picture. I have no problem with TeacherTapp, and no problem with its owners making money. Just be open about it.

2. I was scrupulous NOT to comment on the issue of off-rolling. That’s not what I was talking about. If I was to comment on it however I think it is indeed a really big problem that needs proper investigation, and I’m certainly not disputing the figures referred to above. These TeacherTapp figures are a good starting point – but surely we deserve more than a piece that says “one hypothesis is … ” without properly testing that hypothesis, and also discussing what other hypotheses there might be.

Thank you for replying. I can see your points, but I suspect what’s actually happened is that they used a multi-subject survey to inform several articles.

As for the off-rolling, you can’t lose 9000 kids down the back of the sofa, they don’t all die, they don’t all leave the country and their parents don’t all suddenly discover a burning desire to home educate halfway through their GCSE’s. That only leaves one option, and it’s supposed to be illegal.

Under those circumstances, and having personal experience of ‘managing out’ and pre-emptive exclusion because of SEND, I hope you’ll understand that I am sensitive when someone’s response to an article about it is to question how the data was gathered. I’ve spent years with people telling me it couldn’t have happened so I know it happened under Labour, Coalition and Conservatives and I think that it’s about time that it was dragged out into the open and treated with the contempt and severity that it deserves.

I’ve seen various comments you’ve made on this issue across various different articles, and I wouldn’t presume to think I have your level of knowledge and experience when it comes to the issue of off-rolling. As I’ve said, I think it’s a significant issue that deserves proper, objective, investigative journalism to shine a light on it and bring the facts into the open. If you’re right (and I have no reason to doubt it) it’s clearly not a party-political issue if it’s happened under everyone’s watch.

In response to your last posting, I hope you’ll understand I was never intending to challenge the figures (as you say they reflect other findings) or dismiss the questions that were being asked. My comments were only challenging the possible financial links and conflicts between Schools Week and Teacher Tapp and it was pure chance I made them on this page (rather than the article about experienced teachers being “forced out”, or the Editorial, both of which refer prominently to Teacher Tapp)