Everyone knows the statistic: one in three teachers leaves in their first five years on the job. But what if it isn’t stress, or workload, or pay, that’s the issue? What if it’s pupil behaviour?

Over the past year, as I’ve watched the daily replies of 2,500 teachers to the Teacher Tapp surveys, it has become clear that new teachers bear a serious brunt of bad behaviour. It shouldn’t shock me. Like every teacher, I remember the stomach-churning feeling before a dreadful class and the hours spent tearing my hair out just to get some classes to sit down. Several times I sat and cried the whole way home on the train after enduring back-to-back failed lessons. Yet, as time wears on, it’s easy to forget. Teachers in their fifth or later years of teaching seem to have it much easier.

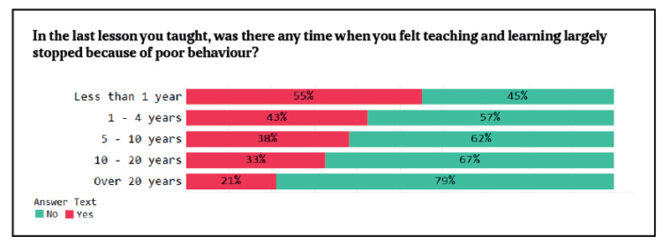

When we asked the panel about the last lesson they taught on a Friday, 55 per cent of new teachers said it was disrupted by behaviour at least once. For those over five years it’s only 30 per cent. Veterans with over 20 years of experience have it down to just 20 per cent.

One in five classes experiencing a disruption is still a lot – but it’s not as bad as feeling like most of your lessons will be disrupted. This is probably why new teachers are much more likely to be dreading school on a Sunday evening.

Isn’t this all natural, though? Handling children is a skill that must be learned. Experienced teachers often think it’s something that new teachers will simply get a grip on, in time. As understandable as that seems, it comes with a cost.

At the end of the year we surveyed the amount of time-off teachers had taken during the year. The group most likely to have stayed at home with a mental health or stress issue? Teachers in their twenties. Almost twice as many teachers in their twenties stayed home at least once for mental health reasons (13 per cent) compared to those in their forties and above (7 per cent).

In line with the Whitehall studies is the 1960s, which proved that lower grade civil servants were more likely to become sick than their senior managers, we also found that classroom teachers with no additional duties – and so teaching the most classes – were those most likely to take time off with stress or mental health issues. In fact, classroom teachers were FOUR times more vulnerable to being absent for this reason compared to headteachers.

If behaviour is a problem for teacher retention, what is the solution? Improving the new teachers’ skills seems an obvious one. But the results of a particular question changed my mind on this.

When Teacher Tappers were asked if behaviour rules were consistently enforced in their school, senior leaders heavily agreed, while classroom teachers were much less convinced (to put it mildly). Secondary schools are particularly affected. Only 19 per cent of heads said rules were not consistently enforced; among teachers the rate was 54 per cent!

For heads, this figure is disheartening. No one wants to be out of touch with the reality of the classroom. But it’s a truism of leadership that you are likely seeing only the very best, and the very worst, of behaviour. Both from pupils and from staff. Seeing an ‘average lesson’ is difficult.

Which is why we think the question of whether or not someone’s last class on a Friday might be an important metric for knowing if they are struggling, or likely to dread the week ahead, or be sick in the coming year. It won’t work in every case. Sometimes it’s just a dud week. Sometimes it’s just a zany-but-lovely class that gets wound up when Friday gets near.

Keeping an eye and asking staff how they got on with behaviour is important, though. As is working really hard on consistency of approach – because even if leaders think behaviour is nailed, the likelihood is that the teachers don’t agree

As a secondary school leader for over 20 years, my view is that many schools have teachers in the Senior Leadership Team who cannot control student behaviour themselves. They have minimal behaviour management skills in their own classes, and are unable to provide leadership in this area. If a teacher is struggling with behaviour management, the last thing they need is a line manager who is hopeless themselves at managing student behaviour.

I have never seen this written about, but I am sure that many of your teacher readers will identify with this problem.

Hi Tom. (Happy Memories eh?) I think there is an important link between behaviour and work load. If your school policy means writing things up and following up on specific issues, that adds to work load. Making time to report things verbally, meet with the students.involved, call parents etc is all very time consuming. If you are in the blissful position as I was in my NQT year in a large inner city comp teaching 500 students a week, being consistent in terms of following.procedures is impossible.

Managers really need to consider this, I think.

My Friday afternoon lesson is complete Bedlam. I could spend my weekend berating myself but I deal with it by knowing in advance what it will be. One day Ofsted may come but until then…

What does concern me after 20+ years is simply how to complete all my work with 4.5 hours of non-contact time? It just can’t be done. One day I will be found out but in the meantime I am counting down my last 3.5 years until my pension lump sum will pay off my mortgage. A shame really as I love being with my students and do genuinely endeavour to do my best for them. Teaching could be a great job. It’s just so sad.

There is only so much teachers can do to compensate for poor parenting. To imagine we can undo the effects of sleep deprivation, exposure to narcotics and verbal abuse at home is staggeringly arrogant. We have come to a place culturally where a large minority parents take no responsibility for their own children’s outcomes. Some are unable to, and a depressingly high proportion just don’t care.